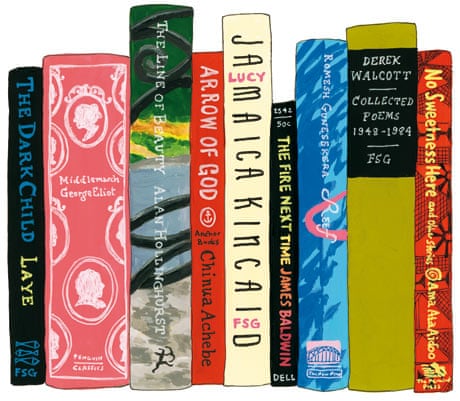

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, novelist: 'All my characters drank ginger beer'

I grew up in a university town in Nigeria. I was an early reader and, what I read as a young child, were mostly British and American books. I was also an early writer. And when I began to write, at about the age of seven – stories in pencil with crayon illustrations, which my poor mother was obligated to read – I wrote exactly the kinds of stories I was reading.

All my characters were white and drank ginger beer, because the British characters in the books I read drank a lot of ginger beer. Never mind that I had no idea what ginger beer was. My characters ate apples and played in the snow and talked about the weather, how lovely it was that the sun had come out. This despite the fact that I had never been outside Nigeria; I lived in a world where the people were mostly black and ate mangoes and didn't have snow and never talked about the weather because there was no need to. I loved those books. They stirred my imagination and opened up new worlds for me, but the unintended consequence was that I did not consciously, actively, know that people like me – little girls with skin the color of chocolate, whose kinky hair did not form ponytails – could also exist in literature.

Then I read Camara Laye and Chinua Achebe, who were a glorious shock of discovery for me. They made me begin to write stories about people who looked like me and did things that I recognised, though a few of my characters continued to drink ginger beer! Achebe's Arrow of God was important to me because it transcended literature and became personal history – I read it as the story of a man who might have been my grandfather.

I came, as an older reader, to love language, and I often reread Derek Walcott and Jamaica Kincaid for that reason. Middlemarch was difficult for me to finish when I first read it as a teenager, but on reading it more recently, I sometimes thought that George Eliot was a version of my feminist self – her sharp, brilliant insight into gender seemed so contemporary. And Reef is a novel that is so beautiful in its evocation of Sri Lanka, a lost paradise of sorts, that it fills me with nostalgia for something I never even had.

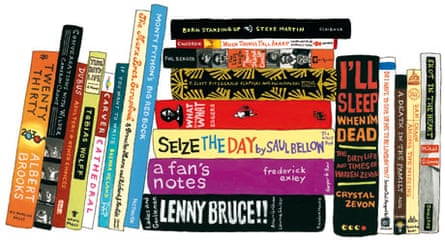

Judd Apatow, film producer: 'As a teenager, I was really unfunny but I wanted to get into comedy...'

In eighth grade, I read Ladies and Gentlemen – Lenny Bruce!! [by Albert Goldman and Lawrence Schiller] I cut out the photos and made an elaborate book report for extra credit. It was gorgeous. My English teacher, Mr Board, claimed to have lost it, but I know he stole it and cherishes it to this day.

Part of what inspired me to read more was a road trip I took with Owen Wilson in 1997. Owen was so well read – he even knew what The New Yorker was! I was embarrassed that the last book I had probably read was Stephen King's Firestarter, when I was 13. He recommended Frederick Exley's A Fan's Notes, which I loved so much that I went on a reading tear for a few years. I remember Owen's saying to me: "I'm jealous that you get to read it for the first time." I didn't understand what he meant then, but I do now.

I chose a few books that were important to me when I was a kid dreaming of becoming a comedian. The Last Laugh was the first portrayal of the comedian's life where I wanted in. When I was older, I read Steve Martin's memoir, Born Standing Up. It answered every question I ever wanted to ask him, including: "Why did you stop doing stand-up?" Now I have to wait for him to host the Oscars every few years in order to see him do it.

As a teenager, I was really unfunny. I think I thought I was funny, but when I read what I wrote, it's really bad. I was not a great-looking kid, either. I wasn't terrible-looking. I was just good-looking enough that if I'd had a decent personality, it would've put me over the top with girls. I don't think I ever got to decent. But I knew I wanted to find a way into the world of comedy.

In high school I realised that if I interviewed comedians for my radio station, they would have to answer all of my questions. Howard Stern, Harold Ramis, Garry Shandling, Henny Youngman, John Candy – I hounded them all into talking to me for an hour. I didn't broadcast most of these interviews. I just wanted to know how to "do it". I interrogated Jerry Seinfeld once about how to write a joke, and he actually told me. Much of my success probably comes from what I learned when I was 16, when I tricked all those nice people into talking to me. Everyone should read this bookshelf. You will reap untold benefits: money, fame, women, and a level of insecurity that cannot be measured by modern technology.

Why doesn't that go away? I'm still looking for the book that will answer that question.

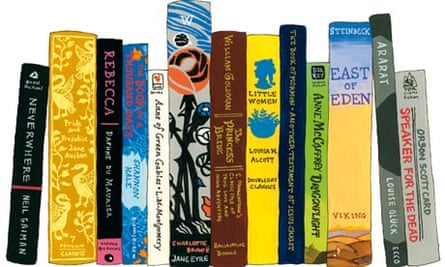

Stephenie Meyer, author of Twilight series: 'These book are greater than anything I could ever aspire to create'

I was the reader. That was my identity in my family: I was that girl who was always in a corner reading; I read my whole life away. I skipped children's books. My dad would read to us at night, and I first began to read on my own by reading ahead in those books. I was seven when I read Little Women for the first time, and it became nearly as real to me as the rest of my life.

I always identified with Jo; I was the tomboy. My big sister was Meg, the pretty one, the sweet one. We didn't have a Beth, but my younger sister was definitely Amy, the frivolous one who liked nice things. I was like Jo in every way except for her passion for writing; I was perfectly content just to read. It wasn't until much later, after I had published three books, that I went back to Little Women and realised that I had become even more like Jo. Now I was a writer, too.

Of all the heroines I was invested in throughout my childhood, Jane Eyre was the one I most identified with, despite my having a happy and supportive family. I liked heroines who weren't perfectly beautiful. I liked that everyone wasn't swept away and captivated by her. Jane Eyre has this huge stubborn streak, which I have, too. I have my ideals, and I really don't diverge from them – it's probably off-putting to a lot of people. Jane is like that, too; she sticks to things even when she's uncomfortable and unhappy and making other people feel the same way. Of course, she's pushed to deeper extremes than I've ever been forced to go to, but I always felt we would see eye to eye. When I think about the books that were formative to me as a writer, I can see how much I was influenced by Anne of Green Gables. When the series starts, Anne is a young girl, and we follow her as she becomes a teenager, an adult, a mother, and finally almost a grandmother. It's so rare that we get to grow up with a character. When I was first imagining my novels, I skipped from Twilight to Breaking Dawn because I was eager to see Bella as an adult.

My editor encouraged me to slow down and show more of her in high school. I don't enjoy a character as much when he or she stays the same age. I want to see what comes next. These books contain threads of what I like to write about: the way people interact, how we relate to one another when life is both beautiful and horrible. But these books are greater than anything I could ever aspire to create. I'll never love what I've done as much as I love what these authors have done. However, for me, just getting to create is its own reward.

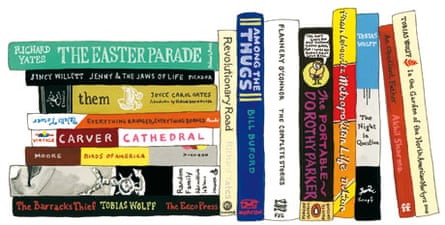

David Sedaris, writer: 'Humour needs some aspect of tragedy to be memorable...'

I was not a big reader in school. It wasn't until I'd dropped out of my second college and was living by myself in a trailer in a very small town in Oregon – I had a lot of time on my hands and nobody to talk to – that I got a library card and started reading. I remember reading Babbitt, because it had been on a list in high school. And I realised that if I didn't have to write a paper, reading was pretty fantastic. I really think you can't progress as a writer unless you read, and the ideal time to read is when you can read generously. It didn't even occur to me that I could have a book of my own in the library someday. That's how you should read.

Tobias Wolff is America's greatest living short-story writer. Sometimes I meet ministers, and I always say to them: "If I had a church, I'd read a Tobias Wolff story every week, and then I'd say to people, 'go home'." There's nothing else you would need to say. Every story is a manual on how to be a good person, but without ever being preachy. They're deeply moral stories; the best of them read like parables.

Raymond Carver makes writing look so easy. Every sentence has 17 syllables and starts with the word 'He'. How hard could that be? And then you realise it's pretty hard. But when I try to read a Raymond Carver story out loud, good luck. The prose is so tone-deaf. It needs more rhythm. So for me as a grown-up, there's not a lot of Carver that appeals to me anymore. When I was much younger, he made writing seem so possible to me. Flannery O'Connor didn't. It does not look easy, what she comes up with. It does not look like anything that someone could sit down and come up with in an afternoon. It's always something to aspire to. If I can ever write anything as decent as one of her stories, I'll let you know. But Raymond Carver, I think he inspired a whole lot of people for that exact reason.

Dorothy Parker is someone who I'd been led to believe was funny. But I find her really sad; her stories are just really sad. Big Blonde is heartbreaking. And I think people find her funny because humour needs to cling to something. I used to go to these shows at Second City, and I would laugh and laugh and laugh, but then afterward I could never remember a single thing I had laughed about. I felt as if I'd had a really nice time, but I think humour needs some aspect of tragedy in order to be memorable. The funny things I remember all have a twinge of sorrow to them.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion