Hot Water in Sunriver

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

South century drive winds into sunriver, the sprawling resort not far from Bend, cutting a path through gothic ponderosa pines and a tan carpet of shed needles. As Officer Kasey Hughes, one of the Sunriver Police Department’s 11 full-time cops, cruised the road on the kind of midsummer afternoon that bakes the skin on your arms, he noticed a white Ford Super Duty following him—too closely, he thought.

Through a traffic circle and into Sunriver’s tiny downtown after another quarter mile of dusty road, the Super Duty was still there. The pickup remained on the police car’s tail as Hughes drove past the Village at Sunriver, the shopping and ice-cream cone destination at the heart of the resort. It stayed with him as he continued into the sleepy residential area where Sunriver’s visitors stay, hunkered in the pines after days spent on bike paths, hiking trails, and championship golf courses.

On it went: Hughes made a traffic stop; the pickup circled around to park near his cruiser. The truck left, circled back, then stopped about 60 feet from the police officer. Hughes decided to radio for backup, just in case the Ford Super Duty’s persistence was as weird as it seemed.

That was five years ago. And indeed, before and since, some things in Sunriver have gotten pretty weird.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

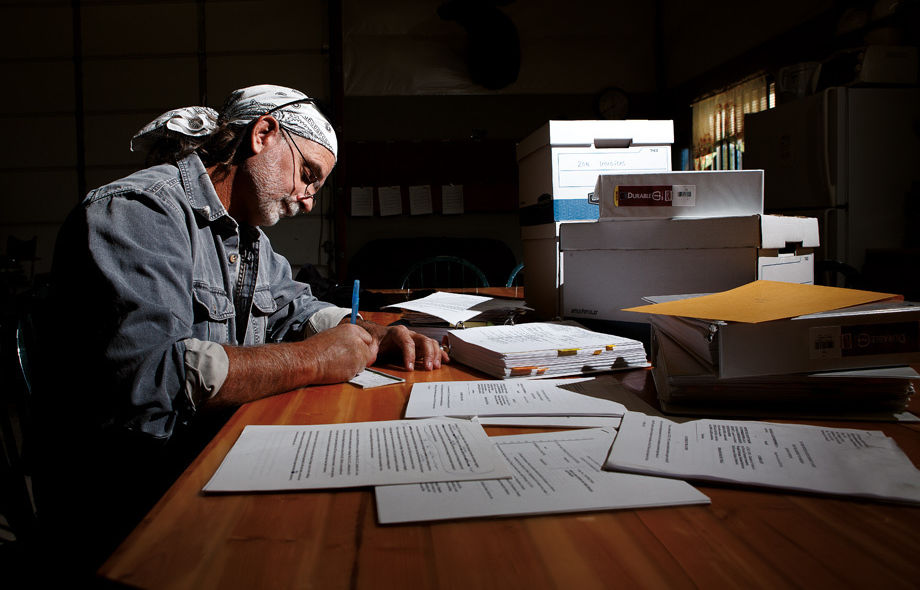

Bob Foster does not seem like a menacing man. He looks like a skinnier version of Willie Nelson, if that’s possible. He’s pensive and polite, a slow-talking guy who loves Lynyrd Skynyrd and can turn the most mundane conversations into a philosophical reflection. After three decades in the area and 20 years running a leading hot-tub service business, the 53-year-old Bend native counts himself among the low-profile army of service workers and small-business owners who keep Sunriver running.

About a million people visit Sunriver every year, some for weekend rental jaunts, others as condo-owning part-timers. About 1,700 people live here year-round. (About 75 percent of Sunriver’s property owners make their full-time homes in the Portland metro area, just 178 miles away.) Those people use a lot of hot tubs: Foster’s business serves about 500 accounts scattered across a vast expanse of cul-de-sac’ed high desert.

“We’re nothing fancy, but we are probably as good a business as there is in Sunriver at doing our thing and treating people right,” Foster says. He drives from one job to another in his vehicle/office, now an F-250, but once a Ford Super Duty pickup.

Foster moved to the Sunriver area in part for its mellow pace, but for the past decade or more, his tranquility has crumbled because of a complicated feud with the small police department that patrols the resort. In the past 10 years, Sunriver cops have written dozens of memos and reports about Foster, photographed him, and videotaped him, compiling a vast record that they claim shows he is morbidly obsessed with the police.

Almost three years ago, two Sunriver cops, Officer Hughes and a sergeant named Joseph Patnode, took the unusual step of obtaining personal, civil stalking orders against Foster. Citizens often pursue this remedy when suffering harassment, but for police officers, who can arrest anyone interfering with their duties, it is atypical. The temporary orders prohibit Foster from coming near the two officers; a judge was supposed to hold a hearing on their validity within 30 days. Thirty days expired on April 4, 2010.

And so, over the past 32 months, police have documented Foster while he performed errands like getting gas and buying groceries and, once, for passing by Hughes twice in a car after Foster’s wife forgot her purse at a restaurant. Foster, who had no prior criminal record, has been arrested three times. He claims that these incidents were innocuous. (As for the episode at the beginning of this story, he says he doesn’t recall it.) Police characterize the run-ins as far more menacing, with hostile glares and uncomfortably close body language.

“It all seems awfully ridiculous to me,” Foster says. “And the reason it seems so awfully ridiculous to me is that I’ve never had a conversation with either one of them.”

After many delays, Foster is finally supposed to have his day in court in January. He will argue that Sunriver’s cops are harassing him because he has publicly questioned how they do their jobs. He also has questioned why Sunriver, where law enforcement made just 78 arrests in all of 2011, needs a full-scale police force to begin with. (Neighboring Bend logged almost 4,400 arrests.)

In the meantime, the hot-tub specialist lives in semi-exile. While Foster still owns his business, he spent much of the past couple of years traveling elsewhere, and says that the legal fight has forced him to live frugally and has crimped the salaries he pays his workers. “Our business and our world has funded every part of this battle,” he says. Lately, he says, he pays himself only when he can.

As Foster awaits a court’s ruling, his saga offers a glimpse of one of Oregon’s premier resort communities: a place created for escape and pleasure but now equipped, almost incidentally, with a government and police force—and all the tensions, political strife, and class conflicts of a real town.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Sunriver began as an army camp. during world War II, about 90,000 members of the US Army Corps of Engineers learned to build roads and bridges in Oregon’s high desert, preparing for the Allied push across France into Germany. At war’s end, the military left behind a vestigial complex of roads and buildings on 3,300 acres where the sun shines 300 days a year.

Starting in 1968, a Portland attorney named Donald McCallum planned a new future for the place along with John Gray, the outdoor-loving visionary who also developed the coastal resort Salishan, Portland’s waterside condo complex Johns Landing, and the Columbia Gorge’s Skamania Lodge. Gray is credited with virtually inventing the idea of a Pacific Northwest resort. As they developed Sunriver, the partners let the curving bank of the Deschutes River and the surrounding wild guide their plans—at the time, a revolutionary effort to synthesize development with the environment. Even the marketing had a modernist spin. A 1968 Oregonian ad pitched “the orderly, progressive creation of a series of interrelated villages.” (The ad also noted the proximity of Mount Bachelor’s 9,000-foot-high ski hill.) They sold their first homesite in 1969. McCallum and Gray repurposed the former Officer’s Club into the resort’s Great Hall, a stately conference facility and party outpost.

Sunriver’s combination of rusticity (canoeing and kayaking are popular) and luxury (some homes have their own aircraft hangars) endured. In the ’00s, prominent visitors like George W. Bush flew into the tiny airport in nearby Redmond, greeted with a choice of a shuttle or a bike. The resort is still growing, bolstered by a sizable addition called Caldera Springs, and even postrecession, homes there still sell for over $1 million.

Until 2002, the Sunriver Owners Association, a volunteer board, ran the place with the help of a general manager. But that year, the association petitioned Deschutes County to create the Sunriver Service District, a kind of mini-government—neither city nor town nor democracy, exactly—to be run by a five-member council appointed by the county commission. Some locals say the district was born largely to make Sunriver’s formerly contract security and fire departments eligible for the state’s pension system. In any case, the district quickly made Sunriver a very well-policed place: its new force, usually 11 officers, beefs up to 19 or more in summer with seasonal bike patrol—one officer for about every 100 year-round residents, compared to nearby Redmond’s ratio of one cop for every 780 people.

As in many resorts and gated communities, the homeowners association kept its hand firmly on the political tiller: the association board and the appointed district council always share two members, to ensure cohesion. In a place engineered for well-to-do part-time residents and vacationers, the mechanics of public safety proved tricky. After one angry driver challenged a citation in court, the Oregon Legislature passed a bill written specifically for Sunriver and Black Butte Ranch, also near Bend, clarifying that police could write tickets on the resorts’ privately owned streets.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Alongside high-desert luxury, the Sunriver area is also home to a different scene: a blue-collar world populated by house cleaners, shopkeepers, and small-business owners essential to the operation of the place.

Foster remembers that when he first came to the area 30 years ago, drifting hippies lived along the Deschutes, putting their clothes in bags to swim to and from a makeshift sweat lodge. No one bothered them. That live-and-let-live ethos charmed Foster, although as a new father he preferred a more conventional lifestyle. He eventually raised three children in Three Rivers, a piney neighborhood just south of Sunriver, and started his business in 1992.

“It used to be like the Wild West,” Foster says. “People who came here from Seattle or Portland thought all of us workers were part of the attraction. It was a lot more free and easy.”

Foster’s house, a 1,100-square-foot A-frame crouched under pine trees along with about 1,000 other homes, wedges between Sunriver’s core and the new Caldera Springs community’s nine-hole executive golf course, man-made kayak lakes, bistro, and lake house. He likes to host poker games in his business’s warehouse off a dirt road, as well as potlucks and band gigs for Three Rivers neighbors. The laid-back milieu long suited Foster, a man who loves the outdoors and guitar, and typically wears jeans and cowboy boots, a white bandanna, and sunglasses.

Then Sunriver began to change.

A lot of the resort’s residents, not just Foster, say the police force ushered in a persnickety new era. As longtimers describe it, the police began spotting every busted taillight, cracked windshield, or bike rider heading the wrong way on a path. “The police department progressively got more and more strict in their enforcement of rules,” says Scott Hartung, a white-haired 15-year resident who manages Sunriver’s airport and served as president of the Sunriver Owners Association. “It was not really the level of enforcement the community was wanting out of a resort.” Hartung and some other influential owners say they’ve tried to get the cops to tone down their enforcement, to little avail. When the service district recently fired its police chief, some locals believed the action—which is now also subject to litigation—stemmed from the cop’s refusal to soften his approach.

The locals’ darkest unease concerns treatment of the resort’s workers: the cooks and cleaning ladies, the construction workers, the hot-tub technicians. As Hartung describes the prevailing mood, “The comment was, ‘If you want to get pulled over, put a bunch of laundry in the backseat of an old car and drive through Sunriver.’”

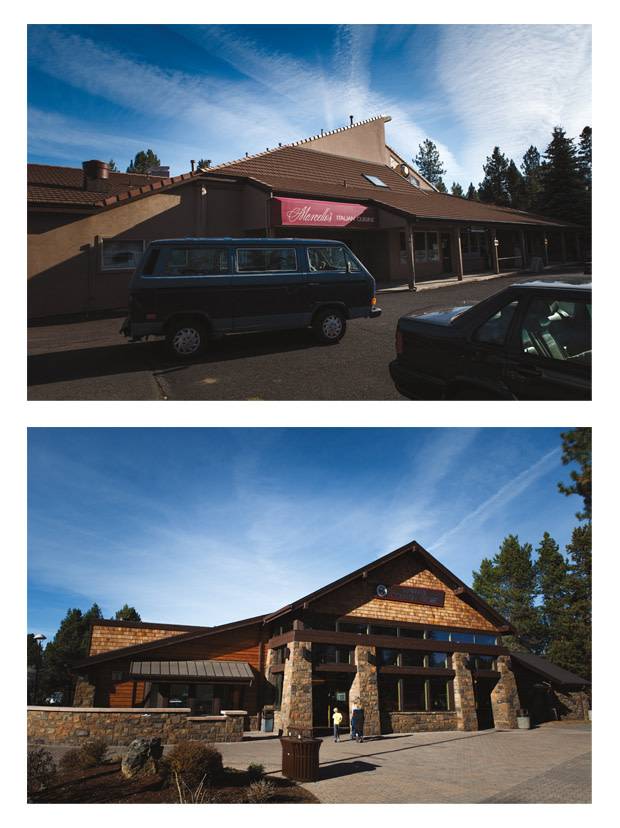

The creation of a governing service district turned Sunriver’s contracted sheriff’s deputies into a municipal police force. During Foster’s conflict with the police, new construction has changed Sunriver.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Bob foster heard that joke. He didn’t like it. He saw seatbelt infraction stings, frequent traffic stops, cars being rifled through. “The Sunriver Police Department would have some poor little housekeeper pulled over, standing in sloshy snow on the side of the road in tennis shoes while they searched her car,” he says.

Foster started attending meetings of the Sunriver Owners Association and service district, speaking out about police. Though his business is headquartered outside the resort and he doesn’t own property in Sunriver proper, Foster set up meetings with board presidents and prominent people there, urging them to halt what looked (at least to him) like an emerging police state.

His perception framed by his hobbyist’s appreciation for American history, Foster believed it his duty to participate in the town’s governance. “We’re supposed to do these things,” he says. “We’re the last free people who can do these things.”

Hartung, whose homeowners association presidency extended into the early days of Foster’s activism, says, “He struck me as a very honest, very direct individual without any kind of selfish motivation. He had a real community spirit. It was, you know, ‘This isn’t what I need for me personally, this is what I think the community needs.’”

The police came to see things differently. Soon after he began testifying about law enforcement, officers began compiling a dossier that fattened with each passing month. Today, the court file on Foster is hundreds of pages long, stuffed with police memos and e-mails about the businessman’s briefest interactions with officers:

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Foster loitered in the parking lot of the police department in his truck, sometimes driving through it several times a day, “facing the department’s back door with his parking lights on ... late in the evening.”

He “pointed his finger and gestured at (Hughes) as he drove past,” “yelled at Hughes in a parking lot,” glared when he saw police, in one case “laughing and staring at the sergeant.”

He revved the engine of his truck behind Hughes.

He called police “the local Gestapo.”

He watched them and took notes, while “staring at us ... ”

He approached traffic stops, once to ask about “the big crime of the night.”

One memo describes Foster laughing like “the villain the Joker from the Batman cartoons.”

Perhaps the most troubling report: that Foster followed Patnode home one night, at speeds of up to 60 miles an hour. Pressed to dismiss the incident later in a deposition, Patnode would not. “Normal behavior is not stalking someone. He shouldn’t have followed me,” he said. “Mr. Foster follows me around. He follows the officers in Sunriver. He does it all the time. He stalks people all the time.”

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Police declined to comment for this article, but the file builds a portrait of Foster at odds with the lithe post-hippie business and family man’s affect. Court documents filed by the officers describe him as a person “more brazen and obsessed as time goes on,” who “carries guns with him,” and “a knife on his belt.” All the same, for a long time, the police did not arrest Foster or cite him for a crime. Instead, after meticulously documenting many interactions with Foster, Hughes and Patnode sought the stalking orders against him.

Neither the officers nor their attorney would comment, but according to Sunriver’s recently ousted police chief, the move wasn’t the officers’ idea. A statement in the lawsuit against Sunriver filed by Mike Kennedy, the former chief, says that members of the Sunriver Service District and the district’s lawyer urged the cops to file their civil complaints. The service district is also paying for their litigation, using tax dollars paid by homeowners. (Current officials with the homeowners association and service district also declined to comment.)

Foster offers a simple explanation for most of the incidents: his constant drives around Sunriver inevitably bring him near the police. He wasn’t following Patnode home that night, he says, but visiting a friend. (That man, now a former friend, disputes Foster’s account in an affidavit.) On a more sinister level, Foster claims that ever since a particularly divisive community meeting in 2007, in which he says he felt he was finally making headway with local leaders, the police have been actively dogging him.

“From that day forward, it’s been follow me everywhere I go,” he says. In one episode, he says he looped through one of Sunriver’s many traffic circles to see if police would continue tailing him. He made it through a couple of times with a cop car close behind. Police, he claims, once videotaped him walking his toddler grandchildren through a grocery store, then putting them in car seats.

Police even follow him outside their legal patrol area. “A disproportionate amount of everything they claim I’ve done, had I done it, has happened outside their jurisdiction,” Foster says. “When you look at the police files, it gets pretty obvious who’s following who.”

Meanwhile, Foster’s daughter hired a private investigator to interview locals about their interactions with cops. The recordings of those talks provide at least a glimpse—slanted though it may be—into the feelings of some members of Sunriver’s working class.

One man tells of being held at gunpoint and ordered out of an RV, suspected of breaking into it. (It was his.) Another woman says she was held at gunpoint after she got out of her car in a parking lot, unaware of why she had just been pulled over. Another woman reports seeing three officers draw guns on an elderly couple in a car. The interview subjects complain of warrantless car searches, vehicle profiling, and the heckling of housekeepers.

Not many people would talk to a reporter about this aspect of Sunriver life. But one restaurant worker who did underlined the perceived double standard: “They don’t pull over the tourists who are drinking at the bar.”

Foster hopes these perspectives help to vindicate him after his case’s repeated judicial delays. (Foster’s own health problems, including insomnia and anxiety, caused some of those delays.) He says the lingering stalking orders make living and working in Sunriver nearly impossible. He has coped by leaving his business in the care of his daughter and a trusted employee, and hiring an extra worker specifically to accompany him around the resort, more as a witness than as an assistant.

In these efforts, Foster says he’s trying to avoid repeats of an incident that occurred in August 2010—one of many in his case that left behind conflicting accounts of what really happened. Foster parked alongside Sunriver’s Spring River Road, the hood of his Super Duty up, and would later say that the truck’s starter had malfunctioned. According to reports filed by Hughes, Foster had stopped near a traffic incident. Hughes wrote that it was the third time he’d seen Foster that day. He summoned a bike officer to take video while Foster fiddled under the hood of the truck. Within minutes, Patnode also arrived with a second camera.

“He was leaning over and staring in my direction,” wrote Hughes. “As I passed his truck, Foster appeared to be taking a picture of me with his cell phone.”

Though nothing came of it immediately, the moment marked mounting tension between Foster and Sunriver police. About a month later, Hughes reported Foster at a gas station “standing outside his vehicle staring at me. I also noticed him washing his windshield very slowly.” Three sheriff’s deputies came to Foster’s business office and arrested him for violating the stalking orders. Foster says the deputies pulled him from behind his desk and cuffed his wrists in front of his screaming grandchildren. It was the first time he’d been arrested.

Foster claims he’s spent $250,000 on his defense, and an estimated $300,000 on running his business in absentia. In August, he filed his own lawsuit: a $566,000 claim against Hughes, Patnode, and the Sunriver Service District for abuse of process. That complaint recently moved from state court to federal court.

Years after they started keeping tabs on Foster (or he started keeping tabs on them), Sunriver’s police aren’t backing down. “He’s stalking our officers,” Hughes said under oath. “It’s not normal to follow a person around for six years.”

Foster may be a citizen-activist who raised an unwelcome stir in a place that literally sells peace and quiet. Or he may be a gadfly gone horribly astray. There is evidence for both possibilities scattered through the huge stack of reports, files, and statements documenting the saga of Bob Foster and the Sunriver cops.

On a recent reading, one particular document stuck out: a receipt for a new starter for Bob Foster’s Ford Super Duty, purchased the day the police videotaped him with his truck’s hood up on Spring River Road.