On the night of Sunday, October 28, 2012, Coast Guard lieutenant Wes McIntosh and the crew of his C-130 transport plane were holed up in a hotel room at North Carolina’s Raleigh-Durham Airport. They’d been relocated there the day before, after winds from Hurricane Sandy had forced runway closings at their base in Elizabeth City. The seven-man flight crew congregated around the TV, flipping between Sunday Night Football and the Weather Channel.

The sinking of the HMS Bounty.

The sinking of the HMS Bounty. HMS Bounty leaving Greenock on the River Clyde.

HMS Bounty leaving Greenock on the River Clyde.It was nine o’clock, and the Denver Broncos had just taken the lead over the New Orleans Saints when McIntosh’s phone rang: the Coast Guard’s North Carolina Sector Field Office—the regional command center in Wilmington—had received a distress email from Tracie Simonin, director of the HMS Bounty Organization. The 180-foot, three-masted ship, a replica of the famous 18th-century vessel, had lost power and was taking on water somewhere near Hatteras Canyon, a treacherous section of the Atlantic roughly 90 miles southeast of the Outer Banks.

No one knew the ship’s exact position or what kind of shape it—or its 16-member crew—was in. Since the captain’s initial email to Simonin at 8:45, the ship’s onboard electronics had failed, and communication was possible only by hand radio, the range of which is limited to line of sight. Storm conditions had intensified beyond the capabilities of the Coast Guard’s cutters and even its Jayhawk helicopters, so the Sector Field Office issued an urgent marine bulletin requesting Samaritan assistance from the handful of vessels still in the region. Only the Torm Rosetta, a 30,000-ton Danish oil tanker, was in hailing range. But it reported back that conditions were too dangerous to respond.

As far as hurricanes go, Sandy was not particularly powerful—on the weekend of October 28, it was fluctuating between hurricane and tropical-storm status—but it made up for that in size and complexity. Sandy would ultimately cover 1.8 million square miles and take on characteristics of what meteorologists call a hybrid storm: in this case, part hurricane, part nor’easter. The Bounty’s last known position—about 100 miles off Cape Fear around noon—put the vessel right in the worst of it, with winds at 60 knots and pelting rain severe enough to render even a large wooden ship invisible on radar. Sending the C-130 was risky, but Coast Guard officials hoped McIntosh could get close enough to establish communication and assess the situation. Once weather conditions allowed, rescue choppers could fly out from Elizabeth City if need be.

The plane took off from Raleigh around 11 p.m. Before long its anti-icing system failed, forcing McIntosh to fly below 7,000 feet. Then the weather radar malfunctioned. McIntosh and his co-pilot, Mike Myers, were now flying using visual flight rules in zero-visibility conditions. Wearing night-vision goggles to help them pick through layers of clouds, they descended to 1,000 feet. Then to 500 feet—right into the brunt of the storm.

By now it was just after midnight. While McIntosh struggled to steer, Myers searched for the Bounty. “I kept asking Mike, ‘What do you see? What do you see?’” McIntosh recalls. Finally, Myers shot back, “I see a giant pirate ship in the middle of a hurricane.”

The plane initiated a sharp circle so the flight crew could get a better look. The Bounty was listing at a 45-degree angle, its starboard side all but submerged. Waves the size of two-story houses crashed over the hull.

There was little McIntosh and Myers could do. The ship’s rigging, more than 100 feet in the air, threatened to ensnare the C-130. Turbulence was so severe that three of the airmen were vomiting uncontrollably. McIntosh made radio contact with John Svendsen, the Bounty’s first mate, who reassured him that the ship would make it until morning, when the crew planned to make an orderly descent into life rafts.

Still, McIntosh was worried. The ship was without power or sails in a hurricane, and he had a feeling the crew was about to go overboard as well. While Myers prepped Svendsen on protocols for abandoning ship, McIntosh radioed the Sector Field Office, which would coordinate the rescue, then called the Elizabeth City base. Helicopter rescue crews were about to embark on one of the most perilous missions of their careers, and he wanted them to know just how serious the situation was. Then he and his team did the only thing they could: they circled overhead, trying to make sense of the feeling that they had somehow flown 200 years into the past.

As the drama of the Bounty’s final hours unfolded on CNN and the Weather Channel, seamen and landlubbers alike were asking the same question: what was a square-rigged ship doing in the middle of a hurricane—a storm that had been forecast for days? Sailors pointed fingers at the captain, Robin Walbridge, insisting that his poor judgment and bravado were to blame. It’s true that Walbridge had tempted fate before. In each instance, some combination of skill and luck had returned the ship home safely.

But the full answer to why the Bounty sank was much more complex than a captain’s rash decision. It was a story decades in the making, a veritable opera of near misses and fantastic schemes involving a dogged captain, a fiercely loyal crew, and an owner who was looking to sell. And in the ship’s last act, an unlikely new character had emerged: a young woman with Down syndrome who, perhaps inconceivably, held the key to the Bounty’s future.

IN SOME WAYS, THE Bounty was lucky to have survived as long as it did. Built in 1960 for the Marlon Brando version of Mutiny on the Bounty, the ship was supposed to be burned for the film’s final scene. Hollywood legend has it that Brando threatened to walk off the set if the vessel was destroyed, so MGM sent it on a worldwide tour to promote the film and then moored it in St. Petersburg, Florida, as a dockside attraction offering public tours.

Thus began a four-decade struggle to keep the Bounty afloat. Wooden ships are notoriously difficult to maintain, especially those docked in warm water. Planks loosen and warp; fasteners corrode. Topsides splinter in the sun and rain accelerates rot. Long, unshelled clams called teredo worms bore through hulls like termites. Even vessels lovingly hauled out of the water and repaired each year disintegrate in these conditions.

By the time the Bounty’s current owner, Robert Hansen Jr., a sailor and the founder of the Long Island heating and air-conditioning company Islandaire, bought the ship in 2001, it had fallen into disrepair. The ship had been acquired by Ted Turner in 1986 as part of MGM’s film library, used in the 1990 Charlton Heston TV movie Treasure Island, and then donated in the early '90s to the town of Fall River, Massachusetts, which planned to use the Bounty to take schoolkids and paying sailing enthusiasts out to sea. But the repairs necessary to obtain Coast Guard classification to carry passengers proved too costly, and the Fall River Chamber of Commerce put the Bounty up for sale for $1.6 million. Hansen bought the ship for an undisclosed sum, but less than the amount owed its creditors, according to reports at the time.

Hansen created the HMS Bounty Organization, a limited-liability company based at Islandaire’s East Setauket, Long Island, headquarters, and hired Tracie Simonin, the company’s staff accountant, as director. He also kept on Walbridge, who’d taken the helm in 1995 at age 46. Walbridge’s widow, Claudia McCann, would later describe him as having two great loves, her and the Bounty; he described the ship as “an extension of myself.” A St. Petersburg native, he’d worked as a diesel mechanic, a pilot, and a truck driver but found his calling on tall ships like the USS Constitution and the Bill of Rights, where he developed a passion for training at-risk kids and children with disabilities to sail. Walbridge had already taken the Bounty through the Panama Canal and on at least two European voyages. He and Hansen hoped to sail it as far as Tahiti, the original Bounty’s last port of call before the famous 1789 mutiny, when mate Fletcher Christian led a small group of sailors against commanding lieutenant William Bligh.

There was reason to believe they would be successful. The tall-ship renaissance, which began just after the U.S. bicentennial in 1976, had grown into a multimillion-dollar industry, with hundreds of ships in North American waters alone. Most of these operate under the Coast Guard classification of passenger vessel or sailing-school vessel. Whether 19th-century originals or modern replicas, they exist within a byzantine system of rules mandating everything from the number of licensed mariners on board to the placement of life preservers.

Keeping a tall ship up to snuff takes a very deep pocketbook, for everything from repairing wooden hulls and canvas sails to maintaining the generators, engines, and navigation systems hidden inside the ships’ historical exteriors. Hansen declined requests for interviews, but one thing is certain: the Bounty proved burdensome from the start. Before he bought it, Coast Guard inspectors estimated it was taking on 20 to 40 gallons of water a minute. Its brokers say it was more like 30,000 gallons an hour—enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool every day. When the bilge pumps failed in September 2001, it took the entire Fall River Fire Department, under the supervision of the Coast Guard, to save the ship. Hansen towed it to Boothbay Harbor, Maine, where it underwent the first of three overhauls, none of them substantial enough to receive Coast Guard classification as a passenger vessel.

And so, as Daniel Parrott, a captain and the author of the 2004 book Tall Ships Down, explained to me, the Bounty operated on the fringe of the tall-ship world, a kind of counter-culture in which vessels try to eke out a profit as what the Coast Guard classifies as moored attractions vessels, which in most cases are prohibited from carrying passengers unless they enlist as crew. The Bounty starred as a merchant ship in two Pirates of the Caribbean movies. Its website advertised sail-training and summer-camp programs, though it was classified to do neither. And according to one former crew member, it sometimes did take on volunteer passengers, including youth groups and corporate teams.

But mostly, Walbridge and his crew made do with what little income the ship fetched through $10-a-head tours, stopping in about 25 ports in the Great Lakes and along the Eastern seaboard each summer—with occasional trips to the West Coast and Europe—then wintering in Florida, Texas, or Puerto Rico. Sometimes, one of the crew told me, they had to use cash from the day’s till to buy groceries. Another crew member, Doug Faunt, said that it was not uncommon for the Bounty to have to wait to dock until more money had been freed up on the ship’s credit card.

Meanwhile, Walbridge worked tirelessly to preserve the vessel. “Robin was the sole vision and energy source for everything associated with the Bounty,” says Jan Cameron Miles, captain of the tall ship Pride of Baltimore II and one of the industry’s most celebrated helmsmen. But that struggle became more difficult every year. In 2010, Hansen put the ship up for sale, asking $4.9 million. It was still on the market when it went down.

Walbridge spent much of 2011 casting about for possible benefactors, including Richard Branson, the billionaire chairman of the Virgin Group, whose family sailed aboard the ship when it visited the British Virgin Islands last winter. “Robin was so proud of the ship,” Branson told me in an email. “He must have shown thousands of people over it but did so with us as if it was his first time. Still brimming with genuine excitement.”

Branson decided not to buy the ship, but as the 2012 tour season wrapped up, Walbridge believed he had secured a fresh infusion of cash and purpose for the Bounty. Both, he believed, could come from the Ashley DeRamus Foundation, a private organization dedicated to raising awareness about Down syndrome. Walbridge looked forward to using the Bounty as an educational platform for people with special needs, and it may have been that new mission, in part, that led him into the storm.

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 25 WAS Walbridge’s 63rd birthday. It was a perfect fall afternoon in New London, Connecticut, where the Bounty had docked just long enough to host the crew of the USS Mississippi. It was a busy time on board: the ship had spent the past four weeks on the rails at Boothbay for a major refit and would depart the next day for the 14-day trip back to Florida. Walbridge freely admitted that the Bounty was underpowered for her size; even with her sails up, she averaged only five knots—about six miles per hour—and St. Petersburg was 1,400 nautical miles away.

That afternoon, Walbridge called his 15-member crew to the Bounty’s capstan, the manual winch at the vessel’s stern where captains have summoned their crews for centuries. For the first time in a long while, say several crew members, he seemed hopeful.

From the start, the captain fostered a devoted crew. I spoke with people who served throughout Walbridge’s tenure on the Bounty, and without exception they talked about their tremendous respect and admiration for the quiet, unassuming man with thick glasses and a small ponytail, describing him as a “genius,” a “father figure,” and a “bad-ass.” They swore time and again that he wasn’t irresponsible. Instead, he was unapologetically—and sometimes myopically—devoted to the Bounty.

Close bonds are common on tall ships. Seasons run six months or longer, and crew members rarely have much more personal space than a coffin. They are notoriously overworked and underpaid—the Bounty’s crew worked 12-to-18-hour days for as little as $100 a week. They are united, however, by their love of being at sea.

Even in that world the Bounty was special. “That ship created friendships stronger than anything,” says Grant Bredeson, a 32-year-old Florida seaman who worked on the ship from 1995 until last May. “The crew is like family, only closer.”

The 2012 crew, Bredeson says, was one of the most experienced the Bounty had ever seen. The well-respected first mate, John Svendsen, a soft-spoken 41-year-old Minnesotan with long blond hair and a perennially serious expression, had joined up in 2010. Two others were licensed captains: 37-year-old second mate Matt Sanders, another Floridian, and Jess Hewitt, a 25-year-old recent graduate of the prestigious Maine Maritime Academy. Four crew members were Merchant Marine-certified able-bodied seamen: third mate Dan Cleveland, 25, Laura Groves, 28, Drew Salapatek, 29, and the ship’s electrician, 66-year-old Doug Faunt, who served as a volunteer.

The remaining hands were a mix of new employees and volunteers. Four paid deckhands in their twenties—Adam Prokosh, John Jones, Josh Scornavacchi, and the youngest crew member, 20-year-old Anna Sprague—had sailed with the ship since the start of its 2012 season. Mark Warner, 33, joined as a deckhand later in the year. The ship’s cook, 34-year-old Jessica Black, and its engineer, Chris Barksdale, 56, had only just come aboard while the ship was in dry dock that September. Finally, there was Claudene Christian, who’d volunteered in May. At 42, she was one of the older crew members and the least experienced.

But that sense of camaraderie was tested on October 25. Earlier that day, tropical storm Sandy had intensified into a Category II hurricane, with sustained winds of more than 110mph. Already, it had claimed the lives of 58 people across the Caribbean, and Coast Guard C-130’s were flying up and down the Atlantic seaboard, issuing radio broadcasts urging mariners to stay in port.

When the crew gathered around the capstan, Walbridge told them he wouldn’t hold it against anyone who wanted to return to the dock. “I know you’ve all been getting a lot of texts and calls from people worried about the hurricane,” he said. He held his hands in a circle, indicating the storm’s expanse. He told the crew he felt pretty confident it would soon track toward land. He reminded them that he’d been in hurricanes before and that the Bounty had always made it.

Walbridge emphasized again that anyone was welcome to leave. No one did. Instead, they began preparing for heavy seas. They took down the topmost rigging and lashed it to the deck. A few crew members told me they’d felt a little apprehension but nothing that would prevent them from going.

“We knew there was weather out there,” says Doug Faunt, the ship’s unofficial white-haired curmudgeon. “But we also respected Robin’s knowledge a great deal. We had a plan, and we were ready.”

That plan, as Walbridge explained it, was to sail due east, wait for Sandy to turn toward land, and then push the vessel into the storm’s southeast quadrant, where hurricane winds are usually weakest. Why he so quickly abandoned that idea once at sea remains a mystery.

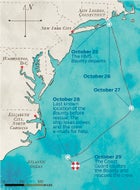

JUST AFTER 5 P.M., the Bounty left New London under clear skies and in light wind. Tracie Simonin posted the news on the ship’s Facebook page, where it was met with notes from fans wishing Walbridge luck.

But instead of sailing east, the ship’s AIS—its automatic indicator system, a kind of GPS tracking device—shows it cutting a sharp angle around the tip of Long Island before establishing a south-southeasterly course of approximately 165 degrees: directly into the hurricane. The Bounty was motor sailing—using engines and sails—and making way at 7.6 knots.

“We were moving as fast as I’ve ever seen the boat move under power,” says Faunt. “We worked those engines hard.”

The pace on board was hectic as the crew prepared for the storm and finished up repair work begun at dry dock. That sort of climate was new to Chris Barksdale, the owner of a handyman business in Nellysford, Virginia. Barksdale was a friend of Svendsen’s with a lifetime of diesel-engine experience, but he hadn’t had much time on the quick voyage from Maine to Connecticut to acclimate himself to such a large marine-engine system.

Barksdale was responsible for maintaining the Bounty’s engine room, two diesel engines on either side of the hull topped by complementary generators that spun electrical power for the vessel. A large fuel bay supplied each. Walbridge had just rebuilt the starboard generator, and he told Barksdale to use the port one as much as possible—so they’d have a fresh generator if anything went wrong. Meanwhile, a supplier’s snafu meant that Barksdale had the wrong fuel filters for the generators—two-micron instead of 20-micron ones, which captured more sediment. But he wasn’t too concerned. “We just decided to be really vigilant, since we knew they’d clog up a whole lot faster,” Barksdale told me. “Everything was running smoothly. It seemed like it was going to be fine.”

As the ship made way, however, Claudene Christian was visibly worried. Her family believed themselves to be descendants of Fletcher Christian, the Bounty’s original mutineer, but she’d only recently come to ocean sailing, crewing aboard a replica of the Niña. The former Miss Alaska National Teenager and University of Southern California song girl arrived on the Bounty last May not with a weathered drybag but with rolling suitcases and a guitar case. Still, she loved tall-ship sailing and proved to be hardworking and a constant source of enthusiasm.

That evening, Christian sent what is now a well-known email to a friend: “You know me, I am not a mechanical person but the generators and engines on this ship are not the most reliable…. They are always stewing over them. I would hate to be out to sea in a storm [and] the engines just quit or we have no power.” As they rounded Long Island, she made what her mother would later describe to the German magazine Der Spiegel as a “distraught” call to her family, then texted a contact who’d be meeting the ship in Florida: “Wow!” she wrote. “Here we go … straight into Hurricane Sandy.”

Friday morning, October 26, found the Bounty sailing about 150 miles off the New Jersey coast, pushed by a 30-knot tailwind. “They were making 10 knots and having a great time,” says Mary Ellen Sprague, mother of Anna Sprague, the youngest crew member on board. “People don’t understand that they were loving it.”

“Robin and I were both watching the storm,” says Simonin. “Every four hours, we would send each other an email update on the ham radio.” Despite the fact that he was no longer heading east, she said, he was still sure his plan would work. The ship’s Facebook page, however, had begun to fill with messages begging the captain to get to shore.

“What Sandy was doing wasn’t a surprise,” says Hugh Willoughby, professor of meteorology at Florida International University and former director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hurricane Research Division. “We knew this was becoming a perfect storm, and it’s very difficult to skirt something of that magnitude—especially if you are in a slow-moving ship.” What’s more, Willoughby adds, Sandy was unique in that her strongest winds were in the southern quadrant. Even if Walbridge made it there, he wasn’t going to find the conditions he’d hoped for.

But the captain was confident; the Bounty had come through plenty of weather before. Several of those times, however, had been close calls. In the fall of 1998, en route from Massachusetts to St. Petersburg, the ship had run into a storm and begun taking on water. What followed was a rescue involving a Coast Guard helicopter, two cutters, a tugboat, and two Navy vessels. A Coast Guard inquiry found that the incident was caused when the captain “misjudged” the severity of leakage.

In 2002, a tropical storm threatened to drag the Bounty across the Gulf of Mexico’s cluttered oil fields. The crew tried anchoring, but the ship still drifted, and Walbridge had to cut the anchor chain to free it. Then, in 2010, as it sailed to its winter berth in Puerto Rico, a storm destroyed several sails, a mast, and one of the two generators. The Bounty was forced to limp to port in Bermuda.

Mitchell Bandklayder, an able-bodied seaman who crewed on several of these trips, insists that it was Walbridge’s mechanical expertise and his ability to take snapped yards and masts and “scarf them back together” that got them out alive. He and others also pointed to Walbridge’s diligence when it came to safety, putting the crew through frequent man-overboard and abandon-ship drills.

Still, the number of incidents surrounding Walbridge has led many to question his judgment. He didn’t do himself any favors last fall when he spoke to a reporter for a Belfast, Maine, public-access station. In a 30-minute shipboard interview first broadcast in August and later posted on YouTube, Walbridge describes taking the ship through 70-foot waves, telling the reporter flat out, “We chase hurricanes.”

Friends and family said that Walbridge didn’t really mean it, but it’s hard to explain what follows: a detailed description of how he drives the ship through major storms. “You don’t want to get in front of it,” he tells the reporter. “You want to stay behind it. But you’ll also get a good ride out of the hurricane.”

BY SATURDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 27, avoiding Sandy began to seem impossible. The Bounty was 150 miles off Norfolk, Virginia. Waves had grown to 20 feet, and it took two people to hold the wheel. Crew members estimate that the wind was gusting at 70mph, screaming through the rigging as it threatened to topple the masts.

“At that point,” says Faunt, “we knew the hurricane wasn’t going to turn toward the land. If we continued our course, we were going to slam into it. We had some sea room, so we thought we could cut back toward land.”

The crew pulled in all but the forecourse, a large forward sail crucial for holding a position and maintaining stability, and changed their heading from SSE to SSW. They were bound for Hatteras Canyon, where they thought they could get by the lee of the storm. It wouldn’t be easy: even on a good day, the Gulf Stream wreaks havoc on conditions there, changing already formidable swells into crashing surf.

The AIS records of the Atlantic during those hours are chilling: a sparsely dotted screen of vessels all making their way to port. Simonin attempted to counter growing vitriol online by reminding mariners of the adage that a ship is safer at sea than at port, but that idea was quickly denounced by other captains. Navy vessels and tankers may go to sea, they responded, but only in the interest of national security or averting major environmental disasters. Did Simonin think either applied to the Bounty? She didn’t reply.

At 7:30 p.m. on the 27th, Simonin received Walbridge’s scheduled email update. He told her that his new plan was to “keep trying to go fast and squeeze by the storm and land as fast as we can.” All else, he wrote, “is well.”

On board the Bounty, the ship’s cook, Jessica Black, was no longer able to prepare meals. She and Christian handed out sandwiches and cold hot dogs.

Barksdale was the first to sustain a significant injury, careening into the side of the vessel, jamming his right hand and rendering it all but unusable. Hours later he was thrown against a metal worktable in the engine room. He sustained a severe gash on his arm and was certain that he’d broken his leg.

Sometime on Sunday the 28th, Prokosh, a bearded, tattooed 27-year-old, was thrown across the tween decks, dislocating his shoulder and breaking several ribs. Christian found a mattress, tacoed Prokosh inside it, and wedged him against the vessel’s starboard side. “Claudene was mothering him,” says Barksdale, “stopping by while she was running around doing her duties to make sure he was comfortable.”

Later that day, Barksdale and Walbridge were in the great cabin in the vessel’s stern when the Bounty hit a large wave. The captain’s lower back struck a bolted-down table, and he crumpled to the floor in pain. With Barksdale’s assistance, Walbridge was able to stand, but for the rest of the voyage he was nearly incapacitated, unable to get around without help.

Down in the engine room, crew members were locked in their own struggle as Faunt, Sanders, Barksdale, and deckhand John Jones tried to keep pace with the water rushing in. “It was over a hundred degrees, we were in shorts and T-shirts and pumping constantly,” says Faunt. A torrent of water was streaming in from the forepeak. Water was pouring from the deck into the crew’s cabins, too. Then, around noon, an urgent all-hands call came from above. Wind had destroyed the forecourse sail.

“Damn near everyone climbed aloft but me,” says Barksdale. The crew ascended more than 50 feet up the rigging, struggling to hold on amid the deeply pitching surf as they furled what remained of the enormous square sail. Once back on deck, they fought to raise the staysail, a small fore-and-aft canvas they hoped would counteract the worst of the violent seas.

The engine room was forgotten. But though the generators’ two-micron filters hadn’t been a problem, another one had emerged: In the chaos, no one had noticed that the sight tube—a narrow piece of glass at the base of the port fuel bay—had broken. By the time the crew realized what had happened, all the fuel had drained from the port tank, shutting off the port engine and generator.

Restarting a diesel engine once it has run out of fuel is a major job. While Faunt and Barksdale got the starboard set running, Sanders struggled to bleed the port system. Eventually, he was able to restart the generator, but the engine remained dead. Meanwhile, water continued to pour in as the ship began to slip its position. To make matters worse, the bilge pumps were clogging with debris. “Things were going south fast,” says Barksdale. “We were fighting and fighting and fighting, but we knew we were losing.”

MANY OF THOSE CLOSE to the Bounty say the fight was lost before the ship ever left dock. It was worn out, they say, and its three overhauls—in 2001, 2006, and 2012—never fully addressed a persistent problem with leaking.

During the 2001 refit—the ship’s biggest overhaul—a good deal of work was done to the hull, but structural weaknesses remained. Deckhands took to calling the ship Bondo Bounty after, they say, they were repeatedly told to fix structural problems with hardware-store polyurethane sealant.

“You could see daylight through some of those fixes,” the ship’s bosun at the time, the officer in charge of maintenance, told me. He asked that I not use his name but says he was told to pull shackles and fasteners from a junk pile at the yard, even though they were rusted through. At one point, he says, the ship’s bowsprit fell and injured two crew members. Most serious, he says, was what sounded like “a waterfall” leaking into the ship at its forepeak, up near the bow, the same place where a torrent would enter during Hurricane Sandy.

I spoke with dozens of people—ship captains, yard workers, surveyors, and former crew members—about the condition of the ship in the years that followed. Most agreed that it had certainly improved since Hansen purchased it. And Coast Guard records show that it consistently passed inspections as a dockside attraction. But, said many observers, the Bounty had persistent problems.

Money was always an issue. Two seasons ago, the ship’s satellite phone broke and was replaced with a handheld unit. Last year, during the Boothbay refit, the ship was scheduled for repainting and recaulking, along with a reconfiguration of the space below deck. Hansen and Walbridge tried to save money by having the Bounty crew do most of the work themselves. One crew member said that he asked the office for a new fuel-filtering system but was told to make do with the old one. When he purchased $40 worth of parts at a hardware store, he says, he was admonished by his superior, who said they’d both “catch hell.”

The engine systems, said a crew member, were “definitely patched together.” In the past, the generators failed frequently, and the starboard generator remained a particular source of concern until Walbridge and a former engineer rebuilt it last summer. That rebuild, Chris Barksdale judged, was sound.

The captain remained circumspect. “Robin would always tell us it’s about give-and-take,” says Grant Bredeson. “Things would break and we’d have to fix them with what we had. Bob Hansen would always look at the bottom line and say, ‘Tell me why we have to do this.’ A lot of time, our answer would get lost in translation. That could get really frustrating.”

The crew loved the ship—and believed it was seaworthy. But several talked about its rate of leakage. One former crew member told me that after the 2001 refit the Bounty continued to “leak like a sieve.” Even last fall in New London, crew members confirmed, the ship had to be pumped several times a day—when it was docked. At sea, the Bounty took on so much water that it had to be pumped out every four hours in calm weather and every one or two hours when it got rough. Said a crew member who left the ship last summer, “They were the worst conditions I’d ever seen.”

That rate of leakage makes Joe Lobley, president of the Society of Accredited Marine Surveyors, suck in his breath. “That’s huge,” Lobley says. “And extremely problematic.” The way he sees it, the rate suggests, at best, serious warping of planks and butt ends. More likely, he says, the entire structure was showing signs of deterioration and fatigue. “A wooden boat should be a lot tighter than that,” says Lobley. “Especially if it’s going to be in the open ocean.”

Citing a pending Coast Guard investigation into the ship’s sinking, the HMS Bounty Organization declined, through its lawyer, to address these concerns directly. But in an earlier conversation I had with Simonin, she took issue with Lobley’s estimation. “Wooden boats leak,” she said. “All mechanical equipment has issues from time to time. But the fact remains that the Bounty was in the best shape of her life.”

ON THE EVENING OF Sunday, October 28, the Bounty’s starboard generator failed once and for all. The water in the engine room was so high that when the ship struck a wave around 6 p.m. and listed to the side, it submerged the starboard engine. The Bounty was now adrift.

Svendsen tried the vessel’s handheld sat phone, but he couldn’t get reception belowdecks. Up above, the wind was screaming with such ferocity that he couldn’t tell if he was talking to an answering machine or Simonin herself. Fearing the worst, he deployed one of the ship’s four emergency position-indicating radio beacons.

The port generator was by now the only thing running, and it, too, would soon be submerged. Faunt and Svendsen helped the ailing Walbridge up to the navigation shack, where, with effort, he was able to use the last of the ship’s electricity to send an email to Simonin via ham radio. At 8:45, she forwarded the message to the Coast Guard; in the hours that followed, McIntosh’s C-130 carried out its vigil circling over the ship.

By 4:30 a.m., rescue-flight crew members throughout northeastern North Carolina were preparing for their 6:30 a.m. takeoff. It soon became clear that they’d have to leave much sooner than that.

Back on the Bounty, the crew was getting ready for a dawn descent into life rafts. They collected their immersion, or “Gumby,” suits and filled drybags with flares, lights, and cell phones. Some added a few personal items—a wallet, a laptop, a pair of glasses, and Faunt’s small teddy bear. They strung food, water, and ditch kits to life preservers and assisted the injured Prokosh into his Gumby suit. At the behest of the C-130 crew, they also put on flotation devices. Crew members recall that no one had been wearing a life jacket, though Faunt says that some people had been clipped into the ship’s safety lines.

The mood was calm and controlled. With help, Walbridge was able to limp around and check everybody’s suits. This was the last time the crew members I spoke to remember seeing him alive.

Then all hell broke loose.

At 4:45 a.m., the C-130 got a panicked radio call from Svendsen: The vessel was capsizing. Fast.

McIntosh put the plane in a quick descent as his crew rushed around the open hold, reconfiguring the ramp for a life-raft drop as rain pelted in. Within minutes, however, the plane hit its bingo-fuel level, the moment when any aircraft must turn around. They dropped the rafts and headed back, not knowing if anyone had made it off the ship alive.

At least 14 did, but they were fighting to survive. When the vessel capsized, it rolled sharply onto its starboard side, sending the crew and everything on deck—including the emergency drybags—tumbling into the sea. Svendsen, who’d been on the radio with the Coast Guard, was the last off the vessel; he broke his right arm and cut up his face as he crashed into the rigging on the way down.

The wind was blowing 50 knots and gusting higher. The sea was chaos. Its force pulled the Bounty’s masts 20 feet out of the water before slamming the rigging—and the tangled crew—back down. Josh Scornavacchi estimates that he was dragged 15 feet underwater. Barksdale says he was trapped underwater multiple times.

“That was the scariest part,” he says. “I didn’t know if I was going to make it or not, but I did know that I needed to get the hell away from that ship.”

No one saw Christian or Walbridge.

Eventually, 13 survivors found each other in the water, searching for the ship’s floating life-raft canisters. Six congregated around a thick piece of oak grating, including the injured Prokosh, who was clipped onto the grating with a climbing harness. Through the surf, Dan Cleveland managed to spy one of the white lines attached to the Bounty’s raft canisters; after it deployed, they eased Prokosh inside and joined him. The raft was taking on water, and they couldn’t find a bailer among its supplies.

Nearby, the seven other crew were struggling, too, and in no time the two rafts were more than a mile apart. Somewhere between them, Svendsen bobbed alone in the waves, clutching a five-gallon tub Walbridge had jury-rigged into a kind of rescue beacon.

More than an hour later, the first Jayhawk helicopter arrived. The much watched Coast Guard video shows the heroic and methodical rescue: the calm voice of co-pilot Jenny Fields as she counts wave intervals, swimmer Dan Todd plunging over and over into the angry sea, rescuing first Svendsen and then those in the first raft; flight mechanic Neil Moulder manning the rescue basket and then announcing that he’d dislocated his shoulder. What the video doesn’t show is Moulder slamming his shoulder against the chopper’s open door, trying to get it back in its socket. Nor does it reveal the full extent of this initial recovery—four aircraft and 22 rescuers—and the massive operation that followed. Before it was all over, the Coast Guard would search the Atlantic for 90 hours, covering 12,000 overlapping square nautical miles.

Once they were safely at the base in Elizabeth City, the Bounty crew spent Monday, October 29, hunkered down in a conference room, wearing surplus jumpsuits donated by the flight crews. Outside, a barrage of reporters tried to gain access, but the crew just wanted to get back to their homes. They say they didn’t hear that day from Simonin or Hansen, who was reportedly at a funeral in Colorado. Ultimately, the Red Cross took them to Walmart for a change of clothes and to a nearby motel.

Christian’s body was found that afternoon, floating a mile south of the ship’s last position. She was unresponsive, with bruises and lacerations over much of her face; the helicopter team continued CPR for the 90-minute flight to Albemarle Hospital in Elizabeth City, where she was declared dead. The search for Walbridge continued for days.

ROBIN WALBRIDGE LEFT BEHIND a complicated legacy and the full truth about why he left New London. His ship was too slow to outflank the hurricane; why couldn’t he have waited? In an open Facebook letter to Walbridge in December, Pride of Baltimore II captain Jan Cameron Miles called his friend’s plan “so amateurish as to be off the scale.” Why, he wondered, didn’t Walbridge turn into port while there was time? “It was recklessly poor judgment,” Miles wrote, “to have done anything but find a heavy-weather berth for your ship, rather than instead intentionally navigate directly toward Sandy.”

The ramifications of that plan are only now coming to light. The Coast Guard and the National Transportation Safety Board have subpoenaed crew members and yard workers, dug through emails and cell-phone records, and interviewed friends and family in anticipation of a two-week hearing in Portsmouth, Virginia, February 12 through 21.

At press time, in early February, one person they had not yet spoken with was Ashley DeRamus, a 30-year-old woman from Birmingham, Alabama. DeRamus has Down syndrome, and over the course of 2012, her family and Walbridge devised a plan to transform the Bounty into an educational platform for people with special needs. They would launch this new chapter in St. Petersburg the weekend of November 9, when the ship was scheduled to arrive in port.

On the face of it, the scheme isn’t quite as far-fetched as it seems—Walbridge had long had an interest in bringing people with disabilities on board—but the more I learned about the particulars, the fuzzier the whole vision got. The idea had its genesis last February, when the Bounty’s dockside photographer, 65-year-old Gary Kannegiesser, met a vacationing Connie DeRamus, Ashley’s mother, in Puerto Rico, where the ship was wintering. Kannegiesser has a background in photo marketing; he and Connie decided to create the Ashley DeRamus Foundation, dedicated to raising awareness about Down syndrome by turning Ashley into a role model. Connie created an Ashley fashion line, and they began touring the country, stopping off for Ashley to recite the Pledge of Allegiance at high-exposure locales like the Grand Canyon and the Rose Bowl parade.

Kannegiesser says the Bounty connection seemed natural. “We knew we wanted to get Ashley’s foundation some exposure,” he told me when I met up with them before the Rose Bowl parade, in Pasadena, beneath a square-rigged ship made of flowers. “The Bounty is the most famous ship in the world. What better place to get the word out?”

At first, Connie sold rubber bracelets printed at the dock. Before long she and Ashley were on the ship itself. Kannegiesser thought they might get more exposure by capitalizing on the Bounty’s role in Pirates of the Caribbean, so he began dressing up like Jack Sparrow. Connie worried that the female crew members didn’t seem very feminine, so she bought them Tahitian dresses. Finally, last August, Ashley crewed for a week on the ship.

DeRamus’s disability doesn’t slow her down: she medaled in Special Olympics swimming 43 times and works as a teacher’s assistant at a special-needs preschool in Birmingham. A petite blonde with a pixie haircut, she tells stories about her time on the Bounty in a voice that is husky and slow but also clear and funny. She wasn’t able to do much work on the ship, she says—her hands are too small to manage most of the rigging, and multiple operations have left her with fused ankles—but she liked being on board. Claudene Christian was her watch partner, and as DeRamus prepared to leave the ship, she found Christian crying in the galley. “I’m going to miss you,” Christian said. “I’ll see you on your birthday.”

The plan was for Ashley, and others, to crew again on the ship, starting in St. Petersburg the weekend of November 9. To launch the venture, Kannegiesser was arranging to fly in several children with Down’s, and the Down Syndrome Network of Tampa Bay confirmed that it would be inviting some 400 families with Down’s children to the event. Ashley would recite the Pledge of Allegiance, kicking off the Bounty’s new chapter as a place of learning and inspiration.

From St. Petersburg, Ashley and several others with Down syndrome would sail with the ship to Galveston, Texas, arriving by her birthday, December 9. Over the winter, Christian would work with them as the Bounty was modified to accommodate special-needs crew. As the summer season got under way, the foundation would pay for other kids with Down’s to join each leg as crew. In 2014, they hoped to attempt the first-ever tall-ship voyage through the Northwest Passage, again with special-needs people among the crew.

It’s unclear how the HMS Bounty Organization intended to reconcile this with its Coast Guard restrictions on carrying passengers. When asked, Kannegiesser said that he didn’t know the Bounty was not classified to do so. He believed that the ship was in good repair but could use a financial boost. “That ship needed a major infusion of resources,” he told me. “We thought we could be that shot.”

The foundation would contribute some money, Kannegiesser says, but the main funding would come from corporate sponsorship. The foundation was in talks, he says, with a soft-drink company, a car dealer, and a producer who hoped to land them a show on the History Channel. Simonin says that was her understanding as well. But Kannegiesser acknowledged that initial sponsor contributions might have amounted only to $10,000 or so. He believed that ongoing media attention would bring in the rest.

The plan made some of the crew uneasy. None were trained to care for special-needs people, and they were already stretched to the limit with their existing duties.

But Walbridge seemed sure it would work. Kannegiesser showed me a series of texts from both the captain and Christian, sent last fall as plans materialized. Walbridge reported that he’d secured permission for the ship’s new mission, and as the Bounty set sail, Kannegiesser wrote that things were moving along nicely on his end.

“Great,” Walbridge responded. “I think we (mostly you) will make it happen.”

It’s unclear how much all this factored into Walbridge’s decision to set sail on October 25. Kannegiesser and Doug Faunt both say that the St. Petersburg event was on the captain’s mind. But Simonin told me that the HMS Bounty Organization was “not aware of any concrete plans with the DeRamus Foundation at that time.”

Waiting for Sandy to pass, she suggested, just hadn’t seemed necessary. “We’ve been in seas like that before, even worse,” she said, “and we didn’t think it was insurmountable. We always had the utmost confidence in him.”

ON A SNOWY DAY in December, the Bounty’s extended family, including more than 100 former crew, assembled in Fall River, Massachusetts, to memorialize Robin Walbridge and Claudene Christian. They tossed wreathes into the ocean, struggled through eulogies, and stood on the deck of a battleship while DeRamus recited the Pledge of Allegiance. It was an exhausting day. The survivors that I spoke to were all having trouble sleeping. Many were in therapy; some were on indefinite walkabouts as they waited to see what’s next.

But first they’d have to make it through the Coast Guard hearings. Coast Guard spokesperson Michael Patterson said that investigators were particularly interested in last summer’s Boothbay refit. Yard workers and crew would be required to testify, and all material witnesses were told to be available for the full two weeks.

The hearings are part of a larger investigation to determine the cause of the accident and whether there is evidence of “misconduct, inattention to duty, negligence, or willful violation of the law.” The investigation will only make recommendations, but those may be taken into account in any future proceedings—whether Coast Guard, criminal, or civil. Svendsen and the other licensed captains on board could face anything from license restrictions to outright revocation. One question will be whether Walbridge was capable of making sound judgments, both before leaving the dock and after he was injured. In extreme cases, subordinate officers can be held accountable if the master is deemed unfit.

The stakes may be highest for Robert Hansen, who could face additional civil and criminal proceedings. Everyone’s actions, from Simonin to the Boothbay yard workers, will be scrutinized. “A lot of things have to go wrong for a ship to sink in these circumstances,” says Martin Davies, director of Tulane University’s Maritime Law Center. “There may very well be plenty of blame to go around.”

And while the Bounty lies at the bottom of the Atlantic, the future may be dim for ships like it. The Coast Guard could choose to enact more rigorous regulations, seeking to reel in these ships sailing out on the fringe. That, says Daniel Parrott, is probably a good thing. “Robin spent so long operating in the margins that he no longer recognized how marginal the operation was. If you spend enough time tiptoeing on the edge of something, sooner or later you’re going to fall.”

Kathryn Miles (@Kathryn_Miles) is the author of All Standing: The Remarkable Story of the Jeanie Johnston, the Legendary Irish Famine Ship.