The Fight Over the Most Polarizing Animal in the West

Twenty years after wolves were reintroduced in the Northern Rockies, many politicians would still love to see them eradicated, and hunters and ranchers are allowed to kill them by the hundreds. But the animals are not only surviving—they're expanding their range at a steady clip. For the people who live on the wild edges of wolf country, their presence can be magical and maddening at once.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The switchbacks on the old logging road still held two-foot-deep patches of snow in late March, when we set off on four-wheelers to scout for wolf tracks in the Boise National Forest, north of Garden Valley, Idaho. The riding was easy lower down, where the hardpack traced the course of a snowmelt-swollen stream through a tight canyon. Spiny rock towers rose from the banks, disintegrating into forbidding walls of scree and timber. If you were an elk or a deer, it would be a tempting place to come for a drink, but you’d be taking your life in your hands. Wolves love a terrain trap.

As we climbed, our engines strained against the grade, mud, and snow. We were headed to a vantage point above a place called Granite Basin, where we could scan hundreds of acres of forest with spotting scopes. Zeb Redden, a 35-year-old soldier based in Fort Carson, Colorado, carried his girlfriend, Joni, on the back of his ATV. Zeb had paid Deadwood Outfitters, owned by Tom and Dawn Carter, $3,500 for the weeklong wolf hunt. I was along as an unarmed observer.

Zeb’s tricked-out, AR-15-style rifle was tucked into a scabbard built into his backpack. A couple of days before, I’d watched him drop to the prone position, press his cheek onto the stock behind his scope, and put a 7.62-millimeter round on a bull’s-eye-painted rock 600 yards away. He was deadly at long range, but he said he probably wouldn’t take a first shot at anything farther out than about 500 yards.

“I’m shooting jacketed hollow-point boat-tails, and at that distance they’ll just go right through. They won’t open up like they’re supposed to,” he’d explained. “If he’s wounded and beyond 500, I’ll keep putting lead on him. But if it’s a first shot, I’d rather get in closer.” I wondered if adrenaline would change his mind if we actually saw a wolf.

Thirty-five-year-old Elijah Coley, our guide, halted on one of the switchbacks and pointed down at a patch of grimy snow, where we saw the unmistakable signature of a wolf paw. About four inches wide, a wolf’s track dwarfs that of a large dog. A little farther on we found another. The midday warmth melted the top layer of snow every afternoon, so we knew the tracks had to be fresh, probably from the night before, possibly from that very morning.

Elijah guessed that we were on the heels of a big black male wolf that he’d captured on a trail camera several weeks earlier. In the grainy images, two wolves are seen walking through scrub brush, their eyes glowing in the infrared flash. The black wolf, which probably weighed over 100 pounds, stood a hand taller than its mate, a two-and-a-half-year-old female whose collar data showed that it was whelped just up the road on Scott Mountain. It wasn’t exactly petite, either, weighing 90 pounds.

There’s a photo of this female on Deadwood’s website now, under a tab that advertises wolf hunts, because it was subsequently killed by Tom and Dawn’s son-in-law, Joe Woodcock, who dropped it from 600 yards. In the image, the wolf looks enormous in its thick winter coat, its forelimbs dangling over Woodcock’s arms as he holds it.

We rumbled up to the overlook above Granite Basin and settled in for a couple of hours of glassing. Elijah spotted a big bull elk resting in a draw about a thousand yards away and noted its impressive antlers. A logger by trade, Elijah goes “shed hunting” every spring to earn extra cash. Wholesalers pay a few bucks a pound for dropped antlers, which might end up on the medicinal market in China, next to powdered rhino horn and elephant tusk. Decorative-furniture makers pay as much as $600 for a matching pair from a trophy bull like the one we were watching. But the elk’s calm attitude suggested that the wolf we’d tracked up the hill was long gone. We soon left, too.

Zeb’s ATV crapped out on the way down. While Elijah rigged a tow rope, I stood with my hands in my pockets, wondering how the others felt about getting skunked.

“What would you do if that wolf came trotting around the corner right now?” I asked no one in particular.

“Shoot it in the face,” Zeb replied.

In the 2013 season alone, hunters and trappers killed a total of 598 wolves in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. Statistics for the previous season are about the same. The fact that wolves are killed in such numbers strikes many people as ironic. U.S. taxpayers paid tens of millions to restore and reintroduce Northern Rocky Mountain wolves under the Endangered Species Act, only to have hunters start blowing them away as soon as they were delisted. But another contingent sees wolf hunting as a public service, a way of reducing livestock depredations and boosting elk numbers at no cost to the public. The political impact that wolves have is grossly out of proportion to their ecological significance or their effect on the regional agricultural economy, but they continue to polarize the West. The relationship between the two factions is toxic, and it has only worsened with the advent of wolf hunting.

Idaho’s and Montana’s wolves lost their endangered species status in 2008, but lawsuits placed them back under federal protection until 2011, when they were finally delisted by Congress. Because of Wyoming’s singularly aggressive wolf-management plan, the state didn’t regain the right to manage wolves until 2012. Since then, Wyoming hunters have killed several high-profile collared wolves on the periphery of Yellowstone National Park, triggering viral outrage among wolf lovers around the world. But Wyoming’s wolf-hunting days were short-lived: in a September 2014 ruling on a lawsuit filed by conservation groups, U.S. District Court Judge Amy Jackson restored federal protections to Wyoming’s wolves indefinitely.

Conservationists are hoping for a similar victory across the border in Idaho, where the state’s wolf population has dropped 23 percent since 2009. “Idaho has been given control over its wolves again, and it has destroyed its breeding populations, driving them down by 60 percent already,” says Don Barry, senior vice president of conservation programs at Defenders of Wildlife. Barry says Idaho’s use of professional sharpshooters and trappers to kill wolves in federal wilderness areas violates the Wilderness Act, and that the Defenders will use every resource available, including lawsuits, to pressure the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to intervene.

If they take legal action, they’re in for a fight. At his confirmation hearing in January 2014, Idaho Fish and Game commissioner Brad Corkill said, “If every wolf in Idaho disappeared, I wouldn’t have a problem with it.”

Some people find it ironic that U.S. taxpayers paid tens of millions to restore Northern Rocky Mountain wolves under the Endangered Species Act, only to have hunters start blowing them away as soon as they were delisted.

Corkill was appointed by Governor C. L. “Butch” Otter, who’s been accused by Defenders of Wildlife of launching a “war on wolves.” Defenders and other conservation groups say that the recent creation of a Wolf Depredation Control Board by the Idaho legislature, at Otter’s urging, is part of a larger effort to push the wolf population over a cliff.

The governor’s office and spokespeople for the Idaho Fish and Game department told me that there are no plans to severely reduce wolf numbers, but the legislators who created the new board have been perfectly clear about their motives. In an e-mail to a Defenders representative sent last March, state senator Jeff Siddoway wrote: “The effort here is to reduce the wolf population to what was agreed to by the State and the [U.S. Fish and Wildlife] Service—10 packs or 100 wolves.” That would mean killing around 550 wolves, or 80 percent of Idaho’s current population.

There wasn’t a single wolf in the Northern Rockies in 1973, when gray wolves became one of the first species listed for protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The eradication of America’s wolves began in the late 19th century, with bounty programs aimed at clearing the way for cattle and sheep. But it took a massive poisoning campaign, launched by the U.S. Biological Survey in the early 1900s, to get the job done. A few isolated populations in Minnesota’s North Woods and on Michigan’s Isle Royale managed to escape the slaughter, but by 1930 gray wolves had been poisoned, shot, and trapped almost to the point of extinction throughout the rest of the Lower 48. Except for a few naturalists who thought this might not be wise—and were ignored—no one saw anything wrong with that.

Things had changed by the late 1970s, when wolves began trickling over the border from Canada into northwest Montana. For one thing, the science of ecology had been developed, and biologists had come to understand the importance of predators to healthy ecosystems. The natural recolonization triggered all the protections under the ESA, and by 1988 there were 30 wolves living along the North Fork of the Flathead River, in and around Montana’s Glacier National Park.

But even with the protections, growth of the border population was slow. Wolf activists began pushing for a more proactive approach, arguing that the ESA obligated Fish and Wildlife to restore “experimental populations” of endangered species wherever they had been eliminated, as long as there was suitable habitat. Yellowstone and the central Idaho wilderness areas offered more than 40,000 square miles of ideal wolf terrain, with few people, fewer roads, and lots of wild ungulates for the wolves to eat. The idea enraged ranchers and hunters, who prophesied a bloodbath of livestock and game, but it gained traction swiftly among scientists and environmentalists.

Seventy-eight-year-old Bob Ream, who at the time was director of the Wolf Ecology Project at the University of Montana and a member of the federally appointed recovery team for the Northern Rockies, also opposed the plan. At the rate wolves were reproducing in Montana, Ream was confident that they would make their way to Yellowstone and central Idaho without any help. But his opposition wasn’t purely scientific.

“The reintroduction, more than anything, really polarized the issue here in the West,” Ream told me last May at his home in Helena. “I think westerners dislike the federal government, but I think they tended to view the natural recovery as sort of an act of God. Whereas the reintroduction was, ‘Those goddamn federal bureaucrats jamming it down our throat again.’ ”

After a fierce political battle and a six-year environmental impact statement (EIS) process, the reintroduction camp won. Over two winters in 1995 and 1996, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service* captured 66 wolves in Alberta and British Columbia and then released them in Yellowstone and central Idaho. The Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan set the threshold for recovery at 100 wolves in each region, with ten breeding pairs producing pups for three successive years. The plan was later revised to include northwest Montana’s naturally recovering population, and the targets were raised to 150 wolves and 15 breeding pairs in each area. With abundant prey and no rival wolf packs, the transplanted wolves doubled their numbers every year for the next three years. The wolf explosion delighted environmentalists and confirmed the worst fears of ranchers and hunters.

For “land rich, cash poor” family ranchers like J.T. and Cody Weisner, wolf depredation of cattle is a serious problem. Unexpected losses can mean not being able to pay property taxes or a child's college tuition.

Twenty years after reintroduction, there are at least 1,700 wolves in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming combined—more than five times the original threshold for recovery under the ESA. Depending on whom you ask, the wolves’ outstripping of recovery goals is either a miracle of conservation or a grievous example of federal overreach and bureaucratic impotence. People who view wolves as the bane of agriculture and hunting are furious that delisting took so long. They’ve accused environmentalists of repeatedly moving the goalposts, claiming, accurately, that wolves met the original threshold for delisting as early as 2000. Conservation groups counter that the original recovery targets were absurdly low, a product of political rather than biological reckoning. They want wolves relisted until experts can determine a viable minimum population size.

Oblivious to the controversy, the wolves of the Northern Rockies are expanding across state borders, gaining footholds in eastern Oregon and Washington. There’s little doubt they’ll go farther still, given that the home range of a single pack can exceed 300 square miles and that youngsters looking to establish themselves in new terrain have been known to travel straight-line distances of more than 500 miles. One long-range disperser from Oregon made it to Northern California in a journey that took him all the way through the Cascades. Colorado and Utah face a wolf migration on two sides. To the north, there are the Northern Rockies wolves, and to the south, smaller but equally mobile populations of Mexican wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. The Dakotas, Nevada, and even Texas are all within striking distance. In November, local environmentalists reported a sighting of what is believed to be a northern gray wolf on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. This is the first time in decades that a wolf has been seen there.

“I’m not much of a killer,” J. T. Weisner told me, cradling the wooden stock of a .270 Winchester rifle that he keeps in the cab of his tractor. We were standing in front of the modest ranch house he shares with his wife, Cody, and their two teenage sons, Qwinn and Ben, near Augusta, Montana. Their oldest child, Teslie, works at an insurance company in nearby Choteau and lives in a house that the family keeps closer to town. J.T., who is 61, passed me the rifle so I could peer through the scope at a hillside about half a mile away, where a black bear foraged in the scrub. Just a few weeks before, J.T. had used the same rifle to kill a wolf not far from where we were standing.

It was a Friday afternoon in May, and J.T. and Cody had been loading up to take Qwinn to a track meet. Suddenly, dozens of cattle came running over the hill behind the house. J.T. thought they might be running from a grizzly. He hopped on a four-wheeler and drove over the hill to see what had spooked the cattle. A black form lurked in the tall grass.

That ain’t no bear, J.T. thought. He lined the animal up on the 300-yard hash of his scope and squeezed the trigger. The wolf ran a few steps, then collapsed. J.T. rode back over the hill without even bothering to look at it. On the way out of Augusta, he called the local game warden to report the kill, which turned out to be an 80-pound male yearling. It was the fifth or sixth wolf that J.T. had in his crosshairs over the years but the first he’d actually shot. “I’m not a killer,” he repeated, shaking his head remorsefully. “I’m really not. I’d just had enough.”

The Weisner Ranch is tucked inside a picturesque canyon along Smith Creek, on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountain Front, where the reefs of the Sawtooths rise suddenly from the plains that stretch to the Great Lakes. The Scapegoat and Bob Marshall wilderness areas lie a few miles to the west. For J.T. and Cody, the wolves’ return has coincided with a rise in livestock losses that threatens to put them out of business.

According to USDA statistics, depredation rates on small family ranches are twice as high as on large operations. A ranch with 1,000 head of cattle can absorb a few dead calves each year, but for “land rich, cash poor” families—as Cody phrased it—a few unexpected losses can mean not being able to pay property taxes or a child’s college tuition.

“You’re gonna lose one or two here and there just from sickness or something, so, you know, you figure that,” J.T. told me. He and Cody used to factor a 2 percent loss into their annual budget. Last year, though, they lost 20 percent of their stock.

Wolf activists tend to dismiss the threat to ranchers’ livelihoods posed by wolves and other carnivores. USDA statistics show that the biggest killers are respiratory and digestive problems, weather, and calving complications, which together account for more than half of all cattle deaths. The National Agricultural Statistics Survey blames wolves for a mere 0.2 percent of annual cattle losses—about 7,800 animals—and less than 4 percent of that total were confirmed as wolf kills by state or federal authorities. But such statistics are somewhat meaningless when you consider that very few of America’s cattle and sheep live in large-predator country, let alone in wolf country. Even in places like Montana, which is teeming with heavyweight carnivores, depredations are disproportionately borne by the tiny fraction of ranches, like the Weisners’, that adjoin wilderness areas.

Some people argue that ranchers who graze on public lands ought to be financially prepared to handle a few predator losses. If they can’t, the argument goes, then the problem is with their business model, not with predators. State livestock agencies also reimburse ranchers for confirmed livestock losses. Last year, the Montana Department of Livestock paid ranchers more than $80,000 for cattle lost to wolves. Along with grazing subsidies and depredation reimbursements, there’s an entire federal agency, USDA Wildlife Services, devoted to killing predators on behalf of the agricultural industry.

In 2013, a portion of Wildlife Services’ $84 million budget went toward killing 321 wolves and 75,000 coyotes.

The agency is a favorite whipping boy for environmental groups, but it’s worth asking: If it was the federal government that eradicated predators in the first place to clear the way for livestock, does the government then have a responsibility to protect businesses that emerged in a predator-free landscape?

For organizations like WildEarth Guardians, which has called Wildlife Services’ mission a “100-year paramilitary assault,” the answer is an emphatic no. Some organizations, like Western Watersheds, are seeking to abolish public-grazing leases altogether. Others, including Defenders of Wildlife, would like to see more money directed toward nonlethal deterrence and controls. They point to the success of projects in Idaho’s Wood River Valley and Montana’s Blackfoot River Valley—where wolf and livestock densities are high and yet conflict has been minimized by employing range riders; the use of an ancient technique called fladry, which involves cordoning off livestock areas with sections of rope festooned with strips of colored cloth; and the development of carcass-removal sites, which prevent wolves and bears from being attracted to bone piles near livestock.

In the Wood River and Blackfoot projects, multiple ranches and outside donors have pooled resources to cover costs. But nothing like that exists where J.T. and Cody live. They told me that they’re interested in nonlethal deterrence methods, but they simply don’t have the financial means to pursue them. They do hire a range rider to keep tabs on their stock during the summer months, but the animals cover a lot of ground and the range rider can’t be everywhere at once.

J.T.’s family has been ranching along Smith Creek for more than 120 years. Every summer, he and Cody turn their stock out onto the Lewis and Clark National Forest, paying a monthly grazing cost of $1.35 per head. That may seem like a pittance, but they resent the implication that they’re freeloading, and you can guess how they feel about the accusation that they’re poor stewards of their stock. For all their losses over the years, only one was confirmed as a wolf kill. Defenders reimbursed the Weisners for it, but they have nothing to show for the dozens of cattle they’ve lost in the woods.

“If I don’t have a right to protect my stuff on public land, then keep the public animals off the private land, because I’m feeding ’em all winter,” J.T. told me over lunch one day in the Weisners’ sunny kitchen. His tone was more exasperated than angry. “I’m not chasing the deer off. You go around and there’s 200 head of mule deer over us. The whitetail are coming up all the time and everything else. I’m feeding them all winter. I’m not charging anybody for it. I’m not getting anything for it.”

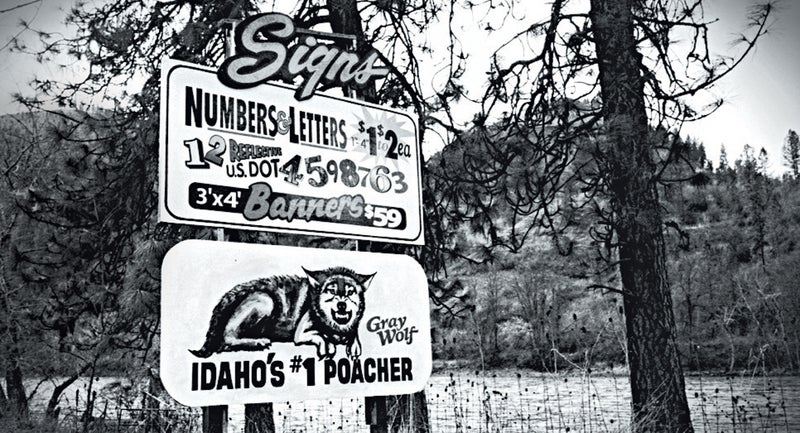

As often as I see bumper stickers in Northern Rockies towns that say things like Save an Elk, Shoot a Wolf and Smoke a Pack a Day, I was surprised to learn that wolf reintroduction actually had significant public support across the region. A 1987 survey by the Fish and Wildlife Service found that more than half of Idahoans supported reintroduction, while only about a quarter opposed it. Among Montanans, the split was closer: 44 percent supported reintroduction, 40 percent opposed it. By 2012, favorable attitudes toward wolves in Montana had plummeted. A Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) survey found that more than 53 percent of households were intolerant of “wolves being on the Montana landscape.” In focus groups, about 81 percent of private landowners and 68 percent of elk and deer hunters were intolerant of wolves. In other words, ranchers and hunters not only still hate wolves, they hate them more than ever.

There was hope that delisting, and the subsequent opening of wolf hunting, would help defuse tensions. Jeremy Bruskotter, a professor at Ohio State University’s School of Environment and Natural Resources, told me he wasn’t surprised to see things go the other way. He pointed to research in Scandinavia and the Great Lakes showing that attitudes toward wolves typically are harshest among people who live near them. “People who perceive high risks (or costs) associated with wolves and low benefits would be expected to show little tolerance for the species,” he wrote in a recent article.

“What it would take to get rid of wolves right now in the Northern Rockies is decades of poison,” says Mark Hebblewhite, a biologist at the University of Montana. “So all the hyped-up fears, it's just not going to happen.”

The 1994 EIS tried to give local stakeholders an idea of what to expect, predicting that a fully recovered wolf population in the Yellowstone area would take a yearly toll of 19 cattle, 68 sheep, and 1,200 ungulates. In central Idaho, wolves would kill 10 cattle, 57 sheep, and 1,650 ungulates per year. Annual livestock depredations would cost between $4,000 and $50,000 in the entire recovery region, and the total loss to the hunter economy would range from $1.6 million to $3 million. However, the EIS anticipated that wolves would give back more than they took, drawing an increased number of tourists and generating a yearly “existence value” of about $17 million.

On the surface, it seems like the economic benefits dwarf the costs, but when it comes to how those benefits and costs are viewed by the public, the picture isn’t so clear. The risks associated with wolves are tied to obvious financial impacts, while the alleged benefits are more abstract and economically dispersed. When a wolf pack kills a calf in a frozen field, it leaves bones and gore scattered on blood-stained snow. The loss to the rancher can be counted in dollars and cents. The same goes for the subsistence hunter accustomed to filling his freezer with several hundred pounds of elk meat every autumn who suddenly has to replace that game with store-bought beef.

In rural communities, where word-of-mouth is often the most prevalent and trusted source of information, Bruskotter explained, a neighbor’s tale of financial woe caused by wolves can trigger emotional responses that are not warranted by the real risks they pose. Couple that with what Ralph Maughan, professor emeritus of political science at Idaho State, calls the “drip drip” effect of years of local media obsession with wolf depredations and the overwhelmingly baleful rhetoric of some state politicians, and you see why wolves have a bad image.

“You can show them science, but they’ll say, ‘Yeah, whatever, that’s a bunch of eggheaded liberals,’ ” Bruskotter told me. “ ‘We live here, we know what they are. We know what they do.’ ”

Few people have had more experience with wolves, or tried harder to educate westerners about them, than 54-year-old Doug Smith, director of the Yellowstone Wolf Project. “It’s value based, or it’s an emotionally based argument, and so facts don’t matter,” he told me. “That’s the tough part. I used to think that if people got educated and had the facts, they’d make good decisions. That’s got nothing to do with it.”

Last April, Smith invited me to go cross-country skiing in the Yellowstone backcountry, right about the time when grizzlies start coming out of their dens. As we slipped through the timbered areas on a cold, bright morning, we shouted “Hey, bear!” every so often, wary of surprising one. When we paused for a snack along Panther Creek, Smith described watching from the same spot several years earlier as a wolf pack chased an elk herd across the sweeping valley before us.

“Life is plain dull and flat when you take those guys out,” he said. Smith believes there are powerful aesthetic and philosophical values in simply knowing that wolves are out there, making wild places wild. Without apex predators, he said, natural landscapes are simply “scene-ified.”

Smith added that the profound top-down influence of healthy predator populations on ecosystems—what biologists call trophic cascades—is the most tangible biological benefit of wolf recovery. In Yellowstone, wolves have helped restore balance between ungulates and native vegetation. Yellowstone’s northern elk herd had ballooned in the absence of predators, to a high of around 20,000, and the outsize population turned the park’s grasslands to stubble fields. They also devastated the park’s willow and aspen, two critical riparian species that provide habitat for beavers, songbirds, foxes, and rodents. Wolves have not only helped reduce elk numbers, they’ve also altered elk behavior, moving them around so that they’re less likely to overgraze any one area.

I asked Smith if wolves have had similar effects elsewhere in the recovery region. “As soon as you leave Yellowstone, wolf density drops,” he told me. “If the density is not at its natural level, the strong ecosystem effects are absent.”

Preserving complex ecosystems is central to the mission of the National Park Service, but it’s a hard sell in the rural communities of the Northern Rockies. Despite ample evidence to the contrary, hunters are convinced that wolves have destroyed elk and deer herds. Current livestock-depredation figures offer a clue as to why you often hear ranchers use words like “deceived” and “betrayed” when they talk about wolf recovery. In 2012, wolves killed roughly seven times more cattle and twice as many sheep as the USFWS had forecasted back in 1995, more than 600 animals in all. That’s a tiny fraction of the region’s six million cattle and 835,000 sheep, but wolf kills make headlines. Word gets around. Politicians take notice.

“I’m prepared to bid for that first ticket to shoot a wolf myself,” Idaho governor Butch Otter told an enthusiastic crowd at a hunting rally in January 2007. Otter went on to blame wolves for killing too many elk and wounding the state’s hunting economy, and he pledged to do something about it.

“Wolves have decimated our elk” is a common rallying cry throughout the region, but it’s a myth. Elk numbers are at or above objective levels in every hunting district in Wyoming and Montana. There are a few places where elk numbers have dropped significantly—the Montana hunting districts just north of Yellowstone; in Idaho’s Lolo, Selway, and Frank Church zones—but even the state game agencies’ own biologists are reluctant to blame wolves exclusively for that. Weather, habitat, food supply, annual hunter harvests, and kills by bears and mountain lions all contribute to fluctuations and distributions of ungulate populations.

Grant Simonds, of the Boise-based Idaho Outfitters and Guides Association, told me that guiding businesses “are worth 50 cents on the dollar” compared with their pre-wolf valuation. Perhaps, but there’s a lot more happening in Idaho than wolf depredation and elk fluctuations. Idaho Fish and Game deputy director Jim Unsworth told me that an increase in the cost of lucrative nonresident license fees, which coincided with the fallout of the Great Recession, probably had more to do with the drop in nonresident hunters than anything else.

When I asked Tom and Dawn Carter of Deadwood Outfitters how wolves have affected their business, I was prepared to hear some version of “they have decimated the elk.” But after four decades of outfitting experience, they had a more nuanced view. Their main problem, they said, was perception. “We do have wolves, obviously, but our elk numbers are still good,” Dawn said. “Good to maybe even very good, but the perception isn’t always that.

“It’s harder to sell hunts,” she went on, because people have “read all these horror stories about the wolves wiping out the elk.” I asked if she thought Otter’s anti-wolf rhetoric was partly responsible for generating such horror stories. “Yeah, there’s probably some of that,” Dawn said, noting that for some guides, the horror stories are true.

Tom remembers his early days guiding for Dawn’s dad in the seventies, when they would sometimes go weeks without seeing an elk. Back then there weren’t any wolves to blame. “The reality of it is that in the sixties and seventies,” Tom said, “they offered hair tags here, either sex, that people could hunt, and the season was too long. I think, as a result of the way the hunting seasons were, they’d shot up a lot of elk.” Without a doubt, he said, recent elk reductions were tied to predation, but it stemmed from more than just wolves. There are also more bears and mountain lions now.

If the alarmism about the effect of wolves on ungulate populations is out of sync with reality, so too is the panic among environmentalists about wolf hunting and the Idaho Wolf Depredation Board. Wolves may be facing new threats in the Northern Rockies, but they are nowhere near extinction in North America. There are 60,000 wolves in Alaska and Canada, and 3,500 in the Great Lakes states. According to Mark Hebblewhite, an associate professor of ungulate biology at the University of Montana, the entire debate over the new agency is yet another example of wolf-driven political theater.

“What it would take to get rid of wolves now in the Northern Rockies is decades of poison,” he told me. Wildlife Services’ Idaho director, Todd Grimm, has already stated that his agency will not use poison to control wolves. “That’s the only way you can get rid of them,” Hebblewhite said. “So all the hyped-up fears, it’s just not going to happen.”

Defenders has used the current 23 percent population decline to forecast the eventual crash of Idaho’s wolf population, but there’s a limit to how much public hunting pressure can influence wolf numbers. The consensus among wolf biologists is that wolves can absorb a 30 percent annual mortality rate without suffering a population decline. Hunting and trapping success rates are very low. Out of the more than 16,000 wolf tags sold in Idaho in 2013, only about 300 were filled, and very few people bagged more than one wolf. The numbers are similar in Montana. The more wolves are killed, the more their density drops, and the harder it becomes to kill them. They get increasingly wary of humans and are more inclined to seek refuge deep in the heavily timbered wilderness areas and national forests, which make up 70 percent of Idaho’s land and a third of Montana’s. Consider, too, that the states’ minimum counts are somewhere between 30 and 50 percent lower than the number of wolves that are actually out there, according to wildlife managers.

“Hop in an airplane and fly from Boise to Bozeman and then Bonner’s Ferry,” Unsworth said, “and look at the amount of wilderness and country we have in this state. You tell me if you ever think the wolves are going to number below 150 in Idaho. I mean, that’s not going to happen. We have so damn much wild country, we have wolves and wolf packs that are existing in our state that probably haven’t even encountered humans.”

If you want to see a wild wolf, your best bet is to head to Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley in the late winter or early spring. It’s easier to spot wolves when they’re silhouetted against the snow and more pleasant when you don’t have to elbow past the droves of tourists who begin arriving by the RV load after Memorial Day. If you cruise Northeast Entrance Road, you’ll eventually find a group of people clustered around tripods at one of the turnouts, sufficiently insulated to accompany Shackleton.

That’s how I met Lynette and Calvin Johnston, from Kansas, and Sian Jones, from Oxford, England, on a chilly morning last April. The three are among Yellowstone’s most committed wolf fans. The Johnstons haven’t missed a year in Yellowstone since wolves were first reintroduced in 1995. Now that the couple have retired, they come three or four times a year, totaling about three months. Jones is on her seventh year.

Through a spotting scope, far across the Blacktail Plateau, we watched the Junction Butte pack gnaw on a winter-kill bison. A young grizzly ambled onto the scene and tugged at the carcass. In an unusual show of defiance, the wolves chased it away. A dozen tourists oohed and aahed as they shuffled to stay warm. Lynette told me it’s not unusual for first-timers to cry. “I think it’s the excitement of seeing something in the wild that they didn’t think they’d ever see,” she said. “I know that’s it for me. It just hooks you.”

All the excitement around wolves translates into a formidable economic force. A 2006 study supervised by University of Montana economist John Duffield found that Yellowstone visitors who come specifically to see wolves generate about $35.5 million annually in the region. Beyond the Yellowstone gateway towns, wolf-tourism dollars are more difficult to gauge, but statistics from the University of Montana’s Institute of Tourism and Recreation Research show that wildlife watching is holding steady among nonresident visitors to the state: in 2013, they spent some $3 billion. About a third of those visitors did some wildlife watching, while only 3 percent went hunting, down from 6 percent five years ago. The hunting economy has been on a downward slope nationally for years, and wildlife-tourism companies around Yellowstone are eager to provide a sustainable alternative.

That’s the hope of Linda Thurston and Nathan Varley, two former Yellowstone Wolf Project staffers who now own the Wild Side, based in Gardiner, Montana. The Wild Side charges about $1,600 per person for the Spring Wolf Watch, which includes lodging, three full days of expert guiding by wildlife biologists, and gourmet locavore dinners. Not bad, considering that a fully outfitted elk hunt will run you upwards of $5,000, excluding license and tag. In late April, I drove down to Gardiner to join the Spring Wolf Watch along with 12 other tourists. All but one of my companions were old enough to be my parents, and they came primarily from the coasts: Orange County, Seattle, Washington, D.C. The only other client under 50, Elinor Waterworth, had come all the way from South Africa.

“Life is plain dull and flat when you take those guys out,” says Doug Smith, director of the Yellowstone Wolf Project. Smith believes there are powerful aesthetic and philosophical values in simply knowing that wolves are out there, making wild places wild.

The first morning, we clambered aboard a small white school bus in the predawn darkness near Yellowstone’s North Entrance. We passed under the Roosevelt Arch and contoured the Gardner River, which was roiling with spring runoff. Lumbering bison halted our progress, triggering an explosion of shutter clicks. East of Mammoth Hot Springs, the canyon opened onto a glacially carved valley, shrouded that morning in fog and rain. We pulled over to watch a nursing bison calf, a bright orange blob of fur set against a backdrop of thousands of charred Douglas firs.

At the Hellroaring Basin Overlook, we found the usual crowd huddled around their scopes, undeterred by bleary weather. Lynette and Calvin Johnston were there. Sian Jones was there, too, along with her mother, who was visiting from England. The Junction Butte pack were chewing on another bison carcass. From about two miles away, it didn’t look like much, but those tiny, distant wolves delivered a powerful emotional experience for Betty Schmitz, a multicultural-affairs administrator at the University of Washington. “I’m actually sort of in tears right now,” she told me. Schmitz was reminded of her husky, who died a year and a half ago. “It’s the relationship between having this domestic dog and then seeing the ancestors in the wild,” she said. “I think it is one of the reasons that I came.”

To John Duffield, Schmitz’s reaction is worth more than the money she brought to Montana. “In my field of natural-resource economics,” Duffield had told me, “we’ve learned that there are also intrinsic values, ecosystem values, passive values, where you go beyond the cash register.” Those non-monetary values travel to the places where Yellowstone tourists come from, and they inform attitudes all over the world. “When you measure those against the costs of the negatives to the livestock and hunting industries, it’s a very clear story: from the viewpoint of social-benefit cost, wolf recovery in Yellowstone was economically justified.”

Capped in a furry hat with a Celtic wolf pin, Jones looked up from her scope and gave me a knowing look as I listened to Schmitz’s story. Her dainty, silver-haired mother had also been eavesdropping.

“I cry often,” she said.

We were sitting around the table one night during the wolf hunt when T. J. Carter—a guide who is Tom and Dawn Carter’s son—started telling everyone about a documentary he’d seen called Blackfish. The film explores the killing of a SeaWorld trainer by one of the park’s orcas. T. J. described the cruel methods used to capture wild orcas and how one captive orca mother mourned for days after being separated from its calf.

“They’re very family oriented,” he said. “They hunt together, they stay with their pods for life.” Joni said she’d seen the movie, too, and another one called The Whale, about an orphaned orca in British Columbia that develops strong bonds with fishermen and dock workers. “They’re so much like us,” Joni said. They could’ve just as easily been talking about wolves.

Many nonhunters have a hard enough time accepting the idea of hunting for food, let alone the allure of killing highly intelligent predators that you’re not going to eat. Zeb grew up hunting elk and deer near Gunnison, Colorado, and he occasionally hunts mountain lions with his brother, an avid houndsman. He told me that hunting predators is thrilling, because “when they feel the pressure on them, they do things that humans do. They double back on their tracks to see if anything’s following them. You’re not at the top of the food chain. You’re hunting something that has the ability and the desire to hunt you as well.”

We didn’t see a wolf all week, but Zeb said he was satisfied with the hunt. “I go out to hunt, I don’t go out to kill,” he said. “I love being outside. Sitting at my binoculars all day is my idea of heaven. And you’ve got to give these animals credit for how elusive they are.”

I visited the Weisners’ place several times in May and June with Ty Smucker, a wolf specialist with the FWP. Smucker spends about half the year trapping and radio-collaring wolves for tracking purposes. He and his volunteer put 20 traps in the ground during the time I was with them but never caught a wolf. The Weisners were more disappointed than I was. When there is a collar in a nearby pack, it’s easy for Wildlife Services to find it in the event of a livestock depredation.

One evening, the Weisners invited all of us to a bonfire at their favorite picnic spot by the creek. We roasted hot dogs and s’mores while the kids told riddles and recited movie quotes, cracking up at each others’ jokes. Cody wore a hooded sweatshirt and held a long-haired Chihuahua mix in her arms. The other ranch dogs, two border collie mixes and Teslie’s German shepherds, scouted the perimeter and sniffed around for scraps. Cody was curious to know if I’d heard stories about how wolves used to attack horse teams in the Old West.

The kids asked me if I’d seen the movie Frozen, and I thought they meant the Disney animated movie about a princess and a reindeer driver who at one point get chased by snarling wolves. They were actually talking about another movie, in which three snowboarders get stuck on a chairlift and encircled by wolves. The kids imitated the terrified snowboarders, laughing hysterically.

Of the three kids, J.T. and Cody pegged Teslie as the one most likely to take over the ranch. She drove a tractor for the first time not long after she learned to walk, and she loved to stay out in the snow and dark with J.T. while he finished his chores. “She’s hard-headed enough to stick with it,” Cody told me once. “I mean, to fight through it.”

J.T. and Cody had discussed what they might do if the cattle came back too short again this year. They could sell off the herd and try to improve their irrigation, maybe stay afloat by growing alfalfa and hay for sale on the market. Or they could subdivide, sell off the land, and try to start again somewhere else. Either option would be a tragedy for the family, regardless of whether they blamed it on wolves, grizzlies, or themselves.

“I know to a lot of people it doesn’t matter,” Cody had told me one afternoon over lunch. “But you’ve got generations that you’re hoping to be able to pass on to one of your kids.” She broke off, fighting back tears. “If it keeps up, we’re done. We can’t. My garden won’t feed us all year round, and I can’t make enough money away from the ranch to take care of everything else.”

The last time I passed through Augusta, I stopped in at Allen’s Manix Store, a small grocery that Cody Weisner’s family has operated since the seventies. When I checked out, Cody’s cousin was at the register. She asked where I was coming from, and I told her I’d been up in the Bob Marshall Wilderness trying to trap a wolf with an FWP biologist, and that I was the journalist who’d been on Cody and J.T.’s place. “What do you think about the wolves?” she asked.

I said I really didn’t know. “What do you think?” I asked.

“I love seeing them down in Yellowstone,” she said. “But it’s just like the buffalo and the Native American culture that was here before. The world has changed. All of that’s gone now, and you can’t bring it back.”

*An earlier version of this story said that the U.S. Forest Service had captured 66 wolves in Alberta and British Columbia. It was the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Outside regrets the error.

Elliott D. Woods (@ElliottWoods) wrote about the drowning death of Tough Mudder participant Avishek Sengupta in January 2014.