The man's deep voice booms from inside his office, his accent thick and Ukrainian and a little menacing. "I want to show you the black market," he says. He is big—a few inches over 6 feet, round in a sturdy way, goatee trimmed short. He strides around his desk, his feet and belly leading the way. He wears shiny black shoes, black pants, a black pinstriped suit jacket.

His name is Alex Holden, although that's not the surname he was born with. The room is in an office park in the grassy Milwaukee suburbs, across the hall from a meat broker that sells beef to school-lunch programs. Hold Security, the name of Holden's firm, is spelled out on the door, slightly crooked, in those reflective letters people stick on their mailboxes. There is no receptionist, almost nothing on the walls. The employee lounge is an unadorned brown sofa from a friend's attic. In one of the few occupied offices, a young analyst named Olga stands in the dark, staring silently at a screen.

Holden settles into a tall black swivel chair, his eyes scanning one of the four monitors lined up on his massive desk. He types, his thick fingers pressing the keys with surprising speed and grace. Images start to appear on his screen. Assault rifles for sale. Counterfeit euros and dollars. Heroin, arranged like a glossy-food-magazine photo of crumbled Parmigiano cheese. Holden types, clicks. Here is Justin Bieber's home address in Calabasas, California. Here's the address, email, and Social Security number for outgoing United States attorney general Eric Holder. All of this in the span of 5 minutes.

Last summer Holden and his firm landed on the front page of newspapers across the country when Hold Security found that Russian hackers had amassed the largest trove of stolen online credentials ever discovered. There were 542 million email addresses and 1.2 billion unique records—email-and-password combinations—in all. Many of the passwords had been decrypted, making them ready for sale on the black market. When I called him a few weeks ago asking to talk with him, he said, "I'm pretty sure after you come visit, you will change your passwords."

Hold Security employs just 16 people. One victim of last year's mass hack, JPMorgan Chase, spends $250 million a year to defend its digital fences, and yet the Russian criminals had been rooting around inside the investment bank's site for months, hacking, digging, stealing. Holden and his team found them.

"The Internet is a bad place," he says. "We are playing an interesting game of defense here." Despite the accent and the heft, Holden himself is actually not menacing at all. He once wanted to be a history teacher and can be windy as a lecturer. He also likes to drop quick, unexpected jokes.

Holden tells me to take a chair. He tilts a big monitor toward me so I can get a better view and gets back to work. The only sounds in the room are the clack of the keyboard and the soft scrape of the mouse on the desk.

As he types, his posture stiffens slightly, and his smile evaporates.

"Good morning, husband!" a small Asian waitress chirps to Holden as he walks into Maxfield's Pancake House, where he's a regular. Holden, who is divorced, grins big. He only glances at the menu and orders his usual: feta–gyro omelet, no toast, side of cottage cheese. "Atkins," he says in his Hunt for Red October accent.

He talks with enthusiasm about his firm, just two years old and very busy. Being Ukrainian helps, he says—he advertises in Milwaukee's free Russian-language weekly for people he can train as analysts. This makes Hold Security uniquely suited to focus on the countries of the former Soviet Union, where much financial cybercrime originates. "We're trying to play where we're good," he says, plowing through his omelet.

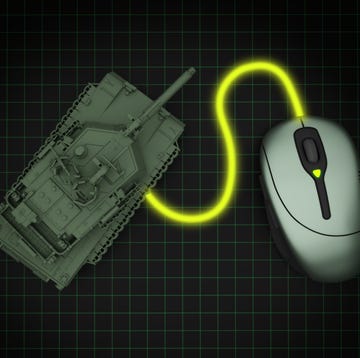

There are routine computer attacks, like spam and basic kinds of malware, that most security systems will catch or stop. Then there are the kinds of cybercrimes that only people like Alex Holden can find in places that most of us have no idea how to even access. He functions with unusual success in a world of endless shadows, unknown people in unknown places committing sophisticated crimes no one can see, never even having to leave their homes. And that's hard. How is Holden able to flourish in a world where corporations and governments are foundering?

When he was a student at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee in 1993, Holden talked his way into a programming job by telling a professor that he knew the Visual Basic computer language (he didn't), then bought a book and taught himself. In the years that followed, most people used the Internet to find information, shop, email friends. Holden, who found the computer and the worlds it contained to be intuitive and compelling, began to explore the tissue that held it together. He never earned his degree, but he did get a job at Robert W. Baird & Co., a global financial-services company in Milwaukee that manages more than $100 billion in assets. When he was just 27, Holden became its chief information security officer.

In 2013 he was working at a small security company called Cyopsis that split in two, and Holden wound up with his own firm in 4,400 square feet of the suburban office park. Hold's primary service is "auditing and penetration testing," he says, which means his team identifies potential weaknesses in clients' networks that allow thefts while also skulking around online to determine whether their information has been stolen. Sometimes Hold Security tracks the hackers themselves.

Online, Holden is always calculating "when to push, when to let people go"—when to press a hacker for information and when to simply sit back and see where the hacker leads him. There is a psychology to his work, but he is hardly a master manipulator, he says. He might, for example, anonymously approach someone for a small favor—"We just need directions to a forum" or "Point us to documentation on something." Now he has not only established contact, he also owes the person. He might repay this debt by passing on some useful bit. Maybe the hacker asks him to recommend a new server for spam. "All I have to say is 'I don't know much about spam, but I know you can buy good servers in this legitimate business.' Now we have friendship. We can engage in conversations. Why not? We don't have to talk all about work. I'm going to ask about family. I'm going to say, how do you feel about what's going on in Ukraine, or what's going on with something in politics. It's important not to disagree."

The files Holden keeps on international hackers are stamped CONFIDENTIAL. They are a record of suspects and known criminals. In some of the files are the hackers from October 2013 who Holden and another researcher discovered had broken into Adobe Systems and stolen 3 million customer credit-card records, along with login data and source code for several titles, including Acrobat—a significant theft because of the potential to invite new waves of viruses through popular software.

In more of the files: the criminals who hacked a limousine-software company and leaked credit-card numbers and embarrassing details about 1 million customers, including athletes, politicians, and movie stars. Holden found them in November 2013.

In still others: The criminals from Eastern Europe who broke into and stole a cache of data from the National White Collar Crime Center, the nonprofit that helps law enforcement investigate and prevent cybercrime.

The total number of hacker dossiers, in all, is about 6,500.

Everyone can see most of the internet, Holden says, but only some people can find the rest, the so-called Deep Web that's not searchable by Google. The Deep Web is hundreds, perhaps thousands, of times larger. Much of it is benign—private company sites and such. "And then there is the black part of the Internet," says Holden—the Dark Web, or Darknet. He enters it on a browser that makes him anonymous and untraceable.

"I'm gonna show you a hacker forum from the inside out," he says, scooting in his chair. He calls up a discussion board, types in two passwords, and gains administrator status, meaning he can move godlike through the forum and read private conversations. A standard board appears, new threads in yellow: "Plastic and Documents." "Passports." "All About Phreaking," or phone hacking.

"They are not giving away kittens or free hugs," he says.

This is the black market?

"It's one of many," Holden says. "We know of maybe 800. We hold seats at many of them."

What happens if, say, your MasterCard was vacuumed up in the breach last Christmas at Neiman Marcus? Holden clicks on another site and up pops a giant picture of a credit card. He logs in. A list appears of Platinum MasterCards for sale, with names, security codes, expiration dates. They are for sale for $5.20 each. "Shop all you can!" Holden booms.

Once Holden uncovers evidence of theft, he has several options. If instructed by his client, his firm can pay to get information back—like a ransom—though he doesn't like that option because it encourages more theft. Once, when his firm caught hackers siphoning information from a client, Holden seeded the illegal download with bad data, spoiling its value. Sometimes, hackers simply hand him information, ratting out others. "We actually see hackers hack each other," he says. "It's competitive."

While we're talking, a CNN producer calls. Holden apologizes and politely asks me to leave—then puts her on speakerphone loud enough for me to hear. The question is about hackers stealing frequent-flyer points. "Is this something you think is the next frontier of data theft?" she asks.

"We are already seeing this," Holden tells her. "For six to 12 months." He begins a long, detailed explanation. The producer sounds like she's trying hard to keep up.

These forums Holden visits, these passwords—how does he get this access? He has required, as a ground rule, that I agree not to name any of his 100-plus clients, which he says include brand-name oil companies and Internet firms, nor to reveal his exact sources and methods, which could compromise his work.

"Hackers share these things," he says. He pauses. "We have good, friendly relationships with them."

When Holden was 5, in 1979, his parents tried to emigrate to the United States from Ukraine, then a Soviet republic, and were denied. Once a citizen applied to leave and was blocked, the USSR became a difficult place, but Holden and his family were trapped.

Seven years later the Chernobyl nuclear power plant melted down north of Kiev, leading to mass evacuations. The disaster was the family's ticket out. They fled to Moldova, then reached a temporary location in Italy where they waited to emigrate. Holden, then 14, was put to work cutting grape vines and moving rocks out of farm fields. He missed a year of school.

Eventually the family made it to Wisconsin, where his parents legally changed their surname to better assimilate. (Holden declined to reveal what the old one was, to protect relatives back home from repercussions related to his work.) Holden was an awkward, husky kid, a loner who struggled so much with English that teachers tried to hold him back a grade. After being assigned to eighth grade, he went home and told his parents he wasn't going back. The school bumped him up to ninth. He also felt deeply confused about the United States, which he had always been taught was evil. Suddenly he was told he'd been lied to his whole life. "There was no guidebook Coming to America for Dummies," Holden says.

Both his parents had been engineers in Ukraine, and they raised Holden and his brother, Rich, to use their brains. Holden became so skilled at chess, his parents hired a private coach. Their father gave his sons almost weekly engineering puzzles: Let's figure out why water freezes at this temperature, and how much energy it gives off. The lessons stuck: Today they're both professional problem solvers—Rich is an assistant professor of informatics and computing at Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis.

As Holden came of age, so did the personal computer. He began to realize its power when a high school biology teacher allowed students to bring one 3 x 5–inch card of notes to the final exam. Holden printed 30 pages of terms and equations on one card, in 2-point font. He graduated six months early.

But Holden has never forgotten how it feels to be a perennial outsider. The frustration and lack of opportunity—it was palpable in the men in south central Russia with whom he connected about 18 months ago. There were about a dozen low-level spammers, all in their 20s, led by a man they called Mr. Grey. Holden chatted up the gang anonymously. At first Mr. Grey's group was only after old lists of emails they could get cheap. But eventually the group became more ambitious, acquiring logins and passwords to access social-media sites, a more effective way to spam because messages look like products endorsed by friends.

By last spring the gang, which Hold Security dubbed CyberVor (vor is Russian for "thief"), was bagging up to 100 million credentials at a time, including data fresher than the old email lists. Holden learned that CyberVor was controlling a botnet—an army of computers run by malware, or malicious software. When an infected user visits a website, hackers use the botnet to see if the site is vulnerable in a way that would allow them to steal data from it. When CyberVor ended up with the largest data theft ever, Holden was the first security expert to know.

Holden wants a steak. After he eats a thick Midwestern slab at a downtown Milwaukee steakhouse, he takes me up to a penthouse bar. He'd mentioned the great views—across the city to Lake Michigan and beyond—but clouds blot out the skyline. He leans back in a tall, upholstered chair, and after a sip of a rum and Diet Coke he says, "Let's do an experiment." When he visited southern Italy, he noticed the manhole covers were square. He asks me, why would they make square manholes?

I sit for some time in uncomfortable silence. Finally, I answer: Old Italy equals cobble streets. A round manhole wouldn't fit among blocks, but a square one would.

He seems a little surprised, but the correct answer is not what interests him. Look how you're folded up in your chair, he says. You're not relaxed. On the other hand, he points out, your head is tilted down and to the left—you're thinking, hard. When he interviews people for jobs, he's interested not just in the answers but in how they react to stress. As he puts it: "We have 'oh my God' moments quite often."

For much of his boyhood, Alex Holden was unsure of his place in the world, his family moving from country to country as if fleeing, the boy searching for an acceptance he rarely felt. When his aloneness led him to something he was good at, that made him feel good, he used his knowledge to do good in return. Now he looks for people who feel the way he did about their place in the world, but who have succumbed to the alienation.

The morning after the bar, Holden shows me one of the confidential dossiers. Here is the criminal's online alias, home address, marital status. Here are pictures—of the hacker dancing, at the beach, with friends. One of them, a young Eastern European, was looking for programming work in 2013. After striking out, he helped design the malware that shredded Target's network that Christmas season, stealing personal data from as many as 70 million customers. Thieves used some of the stolen credit-card numbers to go on spending sprees; banks imposed tight debit-card restrictions, further infuriating travelers and holiday shoppers and inflaming fears about the safety of online information and identities. But Holden echoes what he said during the experiment in the bar, about not getting emotional. "If you're angry about this," he says, "you lose your good judgment."

About 10 years ago Holden was auditing a large financial institution's network. He found a gaping vulnerability. At one moment, "I can see I can access $272 million as an electronic funds transfer," he says. He was alone, just him and a whirring computer. "At that point, your eyes kind of glaze over. And you think about it. This is bigger than most lotteries." For 10 long seconds he sat staring at the monitor. Wow, I don't even know what $272 million would look like.

Then he blinked, shook off the daydream, documented the bug, and got back to work.