Why Noah Went to the Woods

He was a proud Marine who survived three brutal tours in Iraq and had plans to redeploy with the national guard. But when 30-year-old Noah Pippin vanished inside Montana’s remote Bob Marshall Wilderness, he left behind a trail of haunting secrets—and a mystery that may never be solved.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Vern and Donelle Kersey aren’t the type of parents satisfied with hauling their kids to a national park and pitching a tent beneath the floodlights of someone’s motor home. Native Montanans both, when they go to the great outdoors they get all the way there. In the summer of 2010, when Vern’s only week of vacation was pushed into September, the couple were not cowed by the threat of early snow. Along with their two youngest kids, 16-year-old Shelby and 11-year-old Trevor, they set out to hike 30 miles to the Chinese Wall, one of the most magnificent and remote features in the country, a 1,000-foot-high, 26-mile-long spine splitting the Rockies of western Montana.

The Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex—known in these parts as the Bob—is 30 miles wide by 80 miles tall, accessible only by foot and horse (and, in dire circumstances, plane), population zero during winter, then inhabited July through September by five fire lookouts perched like lightning rods on isolated vantage points. At night the lookouts find their only human conversation over the airwaves, their tiny voices crackling in static beneath black skies and swirls of clouds close enough to touch.

The Kerseys bought mummy bags, raingear, and overnight packs, as well as a four-person tent, rain tarp, lightweight stove, and water filter. They weighed out nine days’ worth of freeze-dried food. The Bob is one of the few places in the lower 48 with a robust population of grizzly bears, so the Kerseys packed pepper spray and a 9mm handgun. With no cell coverage, a minor injury like a sprained ankle or hypothermia could be serious.

And that’s why it was strange when, on the fifth evening, shortly after setting up camp and heading off to collect wood, Vern and Trevor came across a man who looked simply unprepared. He wore army fatigues with a nylon poncho over his backpack. He knelt on the trail, filling a plastic milk jug where water trickled through the rocks, pouring it straight into his mouth. The men exchanged hellos. Vern sensed that the stranger wanted to be left alone, so he kept moving, but just to be safe, as the man entered the Kerseys’ camp, where Donelle and Shelby were firing up the stove, Vern lingered on the rocks and listened.

“How you doing?” Donelle sang out. She was vivacious and fit, with a hint of country in her throaty voice.

The man smiled and made a motion to the holster on his hip. “Just to let you know, ma’am, I’m packin’. ”

Big man! Donelle thought to herself. Her own 9mm lay on the log in plain view. But as she studied the man’s face, he looked less dangerous than hungry, thin in the cheeks, maybe as young as her 22-year-old son.

“How long you been on the trail?” she asked.

“Thirteen days.”

“Wow!” she said. “Where did you start?”

He told her he’d walked from Hungry Horse, then spent three days at a lake. Hungry Horse was at least 100 miles away, a tiny town on the northern edge of the wilderness. She asked the man where he was headed.

“I’m just going to follow the Wall,” he said.

Donelle felt her maternal instinct kick in. This is not right. “There’s no trail along the Wall,” she said, showing him on her map where the trail diverged. “And once you get a little down the trail, there’s no camping or fires allowed for four miles.”

The man just nodded.

“There’s plenty of good places around here,” she said, making a welcoming gesture.

“I’m going to keep going.”

“But it’s almost dark.”

“I’ll just curl up under a tree,” he said with a smile.

“We’re going to cook dinner,” Donelle said. “We brought way more food than we can eat.”

“I’m fine.”

“We really don’t want to carry it all out with us.”

“No, thank you, ma’am,” he said.

The man bade them goodbye, and mother and daughter watched him disappear down the trail.

“What if he’s some kind of psycho who’s going to come back and kill us?” said Shelby.

“Nah,” said Donelle. “He just has some things on his mind he’s trying to work out.”

The next morning a storm blew in, icy rain that soon turned to snow. The Kerseys broke camp and trudged out, chilled to the bone even in their new jackets and fleece. Vern built a fire at lunch. The next day the storm was worse, and the waterlogged family still hadn’t reached the trailhead. They spent the seventh night shivering in the tent. Donelle hoped the stranger in his cotton fatigues and surplus poncho had found a place to stay dry.

On August 17, 2010, 30-year-old veteran Noah Pippin arrived at his parents’ home outside Traverse City, in northern Michigan, for a weeklong visit. Earlier that summer, after nearly three years as an officer with the Los Angeles police department, Noah had quit his job and told his parents, Michael and Rosalie, both 60, that he planned to redeploy with the military. He said he was going to vacate his L.A. apartment, haul his possessions to Goodwill, and live out of his car at the National Guard Armory until he could transfer to a unit that was deploying to Afghanistan or Kosovo.

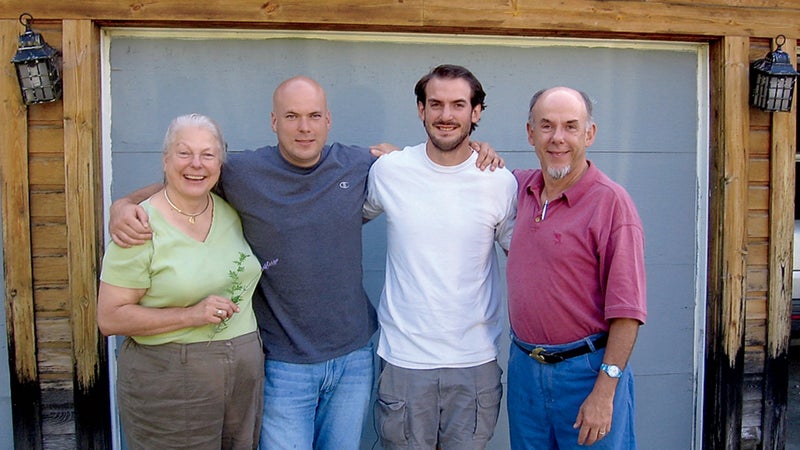

It was an abrupt decision, but not out of character. Noah was already a veteran of three fierce combat tours in Iraq as a Marine and had always seemed most at home among the strict regulations of military life. Many vets can’t tolerate the tedium of a civilian existence, and servicemen routinely discard their possessions before tours, then buy new stuff when they return. Nor did it seem strange to Noah’s parents that he planned to live out of his car. In 2007, after his honorable discharge, Noah had lived in his Buick sedan in a rest area on the freeway near Camp Pendleton, California, while he covered shifts at Lowe’s and gathered letters of recommendation for jobs. No big deal. Rosalie and Mike were thrilled that they had convinced their eldest son to rent a truck and haul his belongings to their house near Lake Michigan. They were doubly thrilled when Noah arrived a day early. He and his dad and his brother Josiah, 29, unloaded the boxes into the basement. Then Noah announced that he would spend that night in a motel.

“It was just plain weird,” said Rosalie, “the beginning of some weird things we did not understand.” But like family often does, the Pippins found ways to explain their son’s behavior. Noah Pippin had always lived by his own code—of duty, structure, and minimal possessions and attachments. He did not date and had never had a girlfriend or, for that matter, a boyfriend. Noah’s father likened the code to that of a samurai warrior. And so it was on this visit. Noah’s plan had been to arrive on August 18, and he meant to stick to it.

Despite the curious beginning, it was a wonderful week. The family took their fishing boat and puttered around the lake. (The youngest of the three brothers, Caleb, 27, lives in Texas and wasn’t there.) Noah’s weight had ballooned the previous year after a knee injury, and Rosalie was so pleased to see him back in good physical shape, smiling and basking in the northern summer sun. She forgave him for listening to his iPod instead of chatting. “Listen to this!” he said, placing the buds on his mother’s ears. Wagner’s Ring cycle, as usual.

Eight days after he arrived, Noah hoisted his backpack into a taxi. Mike and Rosalie had offered to drive him to the car-rental office, but he refused. The date was August 25, and he was due in San Diego for National Guard drill on September 10. He did not mention any plans for the drive home. His parents encouraged him to make a vacation of it. The cabdriver snapped a picture of the family, in which Noah looked intensely serene, his arms draped over the shoulders of his mother and brother. They hugged him goodbye and off he went. Minutes later Josiah found Noah’s watch—an expensive Swiss Army model—and Rosalie called her son’s cell. “Just give it to Josiah,” he said.

For the next few weeks they heard nothing, but that wasn’t unusual. On September 11, 2010—four days before the Kerseys encountered the stranger at the base of the Chinese Wall—the Pippins’ phone rang. It was the sergeant from the California National Guard. Noah hadn’t shown up for drill in San Diego. He was AWOL. Did they have any idea where he was?

The Pippins were alarmed. Given their son’s strict adherence to his moral code, a scenario in which Noah had intentionally shirked his military duty was nearly inconceivable. After several calls to his phone went straight to voice mail, they began to investigate, discovering that they knew far less about their son than they had imagined.

From the car-rental agency, the Pippins learned that Noah had returned the vehicle just two days after his departure—not in San Diego but at the airport in Kalispell, Montana, more than 1,000 miles shy of his stated destination. Noah had never been to the state or even mentioned it. His phone records showed that on August 30 he had called a pizza parlor near Kalispell. The final call, placed on August 31 at 10:45 A.M., was to a different area code and had lasted four minutes. Mike dialed the number and explained to the man who answered that he was looking for his missing son.

“Dad,” said the other voice. “This is your son Caleb.”

Caleb’s own phone bill confirmed that he had received the call—although his records indicated only two minutes. Caleb had no recollection of it. He sometimes works nights and sleeps during the day, and he remembered a call from Noah that woke him up, but he couldn’t be sure it was on the day in question.

That fall, Mike Pippin flew to Kalispell, met with Flathead County detective Pat Walsh, and posted homemade signs around town featuring a color photocopy of a family photo with the handwritten words Missing Veteran and an arrow pointing to Noah. After the Kalispell news aired a story about the disappearance, a hunter named Bob Schall called in. He and his buddies had seen Pippin near the Chinese Wall on September 15 and offered him a cup of coffee, which he accepted, and a hot meal, which he declined. Pippin had walked into their camp late that afternoon, a few hours before he met the Kerseys. His bearing was military: “yes, sir” and “no, sir.” The men talked firearms. When Pippin revealed that he was carrying only a .38, a tiny five-shot revolver with a two-inch barrel, Bob Schall let out a hoot. “Well, son, if you come acrost a griz, you better save the last bullet for yourself!”

With Schall’s help, Detective Walsh tracked down others who’d seen him. Earlier that same day, a backcountry ranger with the U.S. Forest Service named Kraig Lange had been leading a string of horses up a set of switchbacks near the Wall, on a section of the Continental Divide Trail, which runs from Canada to Mexico, when he came across a man sleeping smack-dab in the rut of the trail. Lange asked him to move aside. “Yes, sir,” said Pippin. “I’ll take care of it right away, sir.”

Surveying the small pack and spartan gear—Lange remembers Pippin wrapped in a poncho or bivy sack, perhaps without even a pad—the ranger asked if Pippin was a through-hiker. “What’s that?” said Noah.

“It was pretty weird,” said Lange, who has worked 29 years in the Bob. “I’ve never seen anyone sleep in the trail.” Still, Lange felt no reason to be concerned. “He seemed to be very fit,” Lange said. “Not malnourished or at the end of his rope.” After they passed, Lange and another ranger speculated that they’d just met some sort of “Special Forces kid.”

The Pippins set up a Facebook page called Have You Seen Noah Pippin? A woman called from Missoula to report seeing a homeless man in fatigues who looked just like Noah. A Missoula cop questioned a look-alike on the sidewalk, but when the man stood up he was six foot three—three inches taller than Pippin. The case had gone cold.

The following summer, his photo appeared on the cover of the weekly newspaper in Missoula, where I live, 80 miles southwest of the Chinese Wall. The mystery was irresistible. I picked up the phone and called Mike Pippin.

Back in Traverse City, the Pippins had spent the long winter looking for clues at home. Noah was a methodical man, and in the wastebasket of the guest bedroom his parents found evidence of his planning: an instruction manual for a GPS unit, a package for a waterproof carrying case for the device, a sales tag for a Gore-Tex rain jacket, and a plastic bag from a new pair of Magnum-brand “Professional Boots for Tactical Operations.”

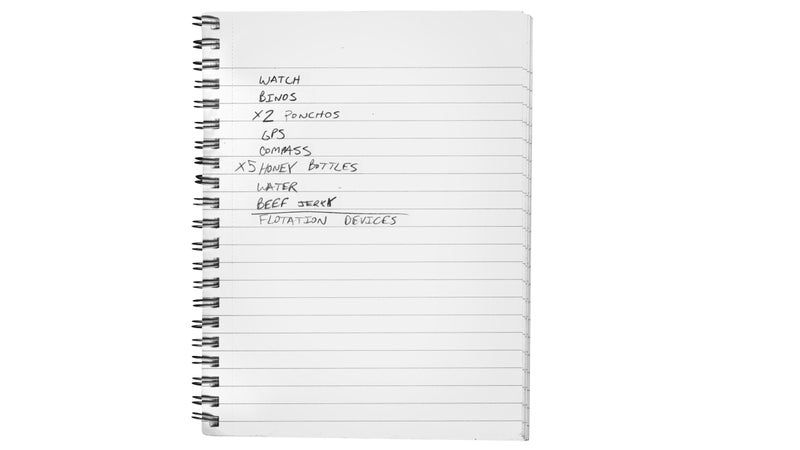

Mike and Rosalie sifted through Noah’s boxes in their basement. They discovered pamphlets about Montana hiking trails that had been mailed to his home in Los Angeles. In his notebook, printed in neat block letters, they found this:

SOUTH FROM HUNGRY HORSE ALONG THE EASTERN EDGE OF THE FLATHEAD RESEVOIR TO THE SPOTTED BEAR RIVER. THEN EAST ON SPOTTED BEAR RIVER (TRAVELING ON IT’S NORTHERN BANK) UNTIL BLUE LAKE(S) IS REACHED.

Here was the first confirmation that Noah had not just wandered into the woods but had plotted his hike for weeks, possibly months. On the next page he had written:

WATCH

BINOS

X2 PONCHOS

GPS

COMPASS

X5 HONEY BOTTLES

WATER

BEEF JERKY

FLOTATION DEVICES

A serious wilderness expedition. But it raised questions. How long did Noah expect to survive the Bob Marshall in September on just jerky and honey? And what was he planning to do with flotation devices? Did he mean a personal flotation device—a life jacket? Why would he need more than one? More puzzling was his destination. Blue Lakes is a nondescript waypoint about 20 miles northwest of the Chinese Wall and would not present itself to someone browsing a guidebook or Googling “hike Bob Marshall” or “isolated wilderness Montana.” Probably the only way Noah could have learned of the existence of Blue Lakes was if somebody had told him about it. But who?

Other discoveries were just as ambiguous. Another to-do list, scrawled on scratch paper in the wastebasket, included “Return vehicle to Toyota Financial.” But Noah had not returned the 2002 Corolla that he still owed a couple thousand dollars on—and which he planned to live in. Instead, he left it in the lot of a Los Angeles shopping mall, where it was promptly impounded and auctioned. The list also included “Close email account(s).” When he was in Iraq, Noah had regularly written his parents from his Yahoo account. If he had been planning to deploy again, why close it?

Months after the disappearance, the Pippins and Detective Walsh were asking the same two questions: Why had Noah walked into the Bob? And where was he now? The simplest explanation was that he had gone hiking, only to be overcome by the elements, a fall, a bear, freezing, or starving. But that didn’t explain why he had concealed his plans from his family.

Suicide was a possibility—especially given Pippin’s recent military service. While only 1 percent of Americans have served, recent studies have shown that vets account for 20 percent of the suicides in the U.S. According to his parents, Noah had seemed preoccupied when they last saw him. He had canceled his accounts on Audible and iTunes and Steam (a video-game site) and given his mother his Kindle, with its 80 nonfiction books—ranging from de Tocqueville to Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein to Nietzsche—saying, “I won’t need this anymore.” It had not struck Rosalie as strange; Noah often gave her his gadgets when he upgraded. But in retrospect his words were ominous. Still, his final known actions did not indicate suicide: Why would a man wanting to die buy all-new gear and plot a hundred-mile hike?

Maybe, then, Noah was still alive. Perhaps he had faked a disappearance and was living a new life, on the streets or in a different country or under a new identity, free of debt and military obligations or some other secret burden he could not share with his family. He was equipped to travel and had last been seen within walking distance of the Canadian border. The Pippins, like any family, clung to this hope, wondering if he had just decided to check out for a while and think things over. His brother Josiah imagined Noah alive and well, and told me, “It will be amusing to hear his reaction to all of this.”

The Pippin home was once a café and boardinghouse for a railroad depot and village that were swept away by a tornado half a century ago. When I visited last October, a homemade sign on the lawn read EGGS $3 DOZ. With a hand-cranked coffee grinder and a woodstove, the house had that comforting smell of plank floors and the old-timey ticktock and hourly yodels of a cuckoo clock. Even with the computers and fax machine, the Pippin home resembled the 1800s as much as the 21st century.

In 1988, after stints in Memphis and Berkeley, the Pippins moved to northern Michigan, where Mike landed a job as a pension adviser. They are devout Christians, and Rosalie said the move was partly a retreat from the chaotic and corrupt world around them. “We wanted more control over our children’s exposure to people,” she told me. “When you see bad influences, you think: Let’s not take them into our home.” Both Mike and Rosalie had grown up with the television always on. They wanted their boys to be outdoors, climbing trees. They required Noah and his brothers to clean the chicken pens and collect the eggs.

Noah and his dad and his brother Josiah unloaded the boxes into the basement. Then Noah announced that he would spend the night in a motel. “It was just plain weird,” said his mother, “the beginning of some things we did not understand.”

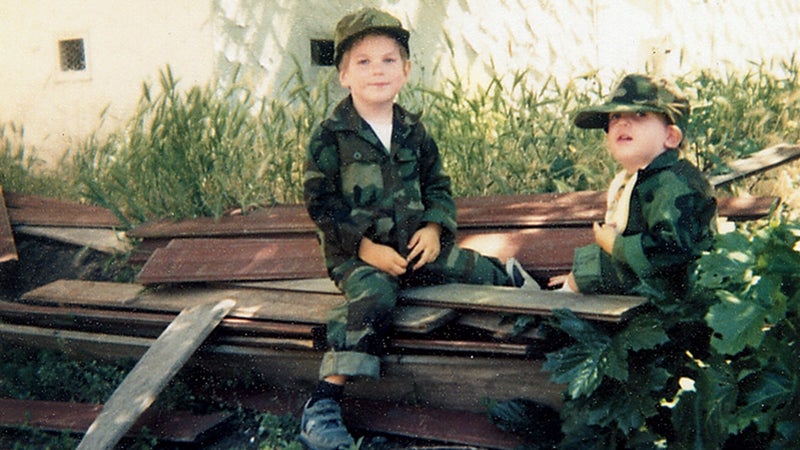

The Pippins created a sheltered haven. Noah was a hardworking kid who tromped miles though the forest to the golf course where he was a groundskeeper. He never so much as sampled a joint. But for Noah, the pastoral idyll was mostly a proving ground for his real passion: the worlds he created in his imagination. With his brothers and friends, the woods became fantastic battlefields for ninjas, warriors, commandos, and space creatures. At night the boys played long games of cover and concealment, searching for one another with flashlights.

Soon enough, Noah discovered the dreaded television and video games. “I had everything at my place he wasn’t allowed at his,” remembers Patrick McDonnell, one of his closest childhood friends. “Cable TV, video games out the wazoo, freedom of expression, swear words. It was his escape into the world he’d often read about but wanted to experience. He’d spend all weekend at my house, glued to the television in my room, channel surfing and soaking everything in like a sponge.”

A big kid, Noah played on the high school football team, but by then he was mining the experience for irony. While he liked the discipline and physical training, what he seemed to relish most—to boast about—was the fact that, in his two years on the squad, the team didn’t win a single game.

In 1998, Noah went off to Central Michigan University, a three-hour drive from Traverse City. He changed his major from journalism to philosophy. Noah had chosen to be baptized when he was 18, but now, citing Nietzsche and Richard Dawkins, he declared first that God did not exist and then, putting a finer point on it, argued that because the existence of God could never be scientifically proven one way or the other, it wasn’t worth debating. Unlike his Christian parents, who tried repeatedly to bring him back to God, Noah was a Man of Reason. After two years, he transferred to Michigan State University for prelaw, a move that his father now thinks was a mistake. “He just didn’t fit in,” said Mike Pippin. “Noah would like to go running—in a snowstorm—and then he’d come back to the dorms and everyone was sitting there smoking pot.” Noah’s grades declined, and in the summer of 2002 he left college without a degree.

Pippin was inducted into the Marine Corps on January 22, 2003, just as the nation was preparing for war in Iraq. He joined less for political or patriotic reasons than for the discipline, strength, and adventure it promised, and—above all—the honor. It was a word Noah used often, one he applied not just to his heroes from war memoirs and science fiction but also to the authors—Plato, Darwin, Adam Smith—whose strict adherence to truth had altered the course of civilization.

“In a very Aristotelian sense, he tried to have a good habit,” said fellow Marine Aaron Nickols, who described Pippin as principled, deliberate, and intentional. Aristotle tells us that we are what we repeatedly do, and therefore excellence is not an act but a habit. “He never wavered from what he believed,” said Nickols. “At all.”

Noah shipped to Iraq in 2004. There, in the presence of his fellow Marines, he seemed embarrassed by his doting parents, letting their care packages sit unopened while his comrades jealously imagined the home-baked brownies and local dried fruits inside. In his two tours in Fallujah and one in Ramadi, Noah saw some of the worst fighting of the war, but he didn’t speak much about it to his parents. During the 30-day leave between his first and second tours, he didn’t even visit home, choosing to remain in the barracks reading and gaming.

Although aloof, he could be tender with his mother, addressing her as Mutti and Madame Le Goose. From Fallujah he sent chatty e-mails about care packages (“I gobbled the cherries right up!”), about the family getting a new animal (“A FREAKING COW???!!! … LOL! Ohhhh man, I thought we had trouble with the chickens”), and about their mutual struggle to maintain their weight.

On September 29, 2006, during his final tour, Noah was almost killed. While he was manning the turret of a Humvee patrolling Fallujah, an SUV sped out of an alley. “Truck in convoy!” came the warning on the radio, but Noah and his team never even saw it. The SUV detonated, and the Humvee erupted in flame, lifted on two wheels, then somehow managed to land flat. The men were knocked unconscious but quickly came to and leaped from the burning wreckage. Noah was confined to the camp for medical observation but returned to work within 24 hours. “It was just a matter of time in my line of work,” he wrote to his father. “I’ve made a full recovery except for my hearing which is pretty much shot. … Please don’t tell mom cause I know she’ll just make trouble for me!”

Mom learned soon enough. “Noah, God saved your life in this last blast and those of your buddies,” she wrote. “For the last 4 years, your Dad and I have been asking Him to save your life until your surrender to him. Oh Noah, turn away from your life of self-will!”

But Noah did not surrender. His rejection of his parents’ religion bordered on defiance. The dog tags he wore in combat were stamped just below his name and blood type with the word ATHEIST. During one visit home, he told his parents that he had employed the services of prostitutes. He also showed them photos of dozens of Iraqi corpses, the results of his efforts as a mortarman. One night his father told him how they had looked up at the moon above Michigan and realized that Noah had seen the same moon from Iraq, and they wondered what their son was thinking. “The only thing I thought about was that there are people out there who are trying to kill me,” Noah laughed, dismissing the chance to confide any more.

“Ever since he was a teenager, he just never liked what we put out on the buffet,” said Mike Pippin. “He did not accept our belief that Jesus is the Messiah. It just wasn’t for him. I think it’s obvious in retrospect that he is well suited to be a soldier or a policeman, and I wasn’t that kind of person myself and I found it difficult to recognize.”

When I visited the Pippins, 14 months after their son’s disappearance, they were beginning to accept the possibility that Noah was dead and were combing their memories of his last visit for clues about his emotional state and intentions. As a child he had been diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and medicated with Ritalin, and during his visit it had seemed to Rosalie that his symptoms were returning. As he sat at the dining room table, Rosalie mentioned a new book about the condition, which she suffered from as well. The author proposed that people with attention deficits were gifted in ways not always appreciated by society.

“Being this way is not an advantage,” he snapped at her. “I’m defective.”

“He was just so hard on himself,” said Rosalie. Three days before his departure, at a party at Good Harbor Beach, she tried to spring Noah from his shell by introducing him to a family friend—also a Marine, also a vet. The men debated religion until Noah cut it short. Later he complained that discourse with the Marine had been like wrestling a beanbag. Any time Noah won a decisive point, the man rehashed the same emotional appeal. He inserted his headphones, oriented his lawn chair toward the sunset, and returned to his hardcover, A House Built on Sand: Exposing Postmodernist Myths About Science.

Noah simply hadn’t been himself that week. “Normally, he would have laid on the couch and I would have scratched his back and he’d tell me the things deep in his heart,” said Rosalie. “But this time we just never got to it. He just didn’t open up.”

Phone and credit card records subpoenaed by Detective Walsh reveal the activities of Noah Pippin’s final week in civilization. After leaving his parents’ house midmorning on August 25, Pippin ate the next day at a diner in Moorhead, Minnesota, nearly 800 miles away. Late that night, he called a motel in Hungry Horse. The following day he dropped off the car at the Kalispell airport, another 1,000 miles to the west. A taxi shuttled him from the airport to Hungry Horse, a settlement of 934 souls on the Flathead River.

For Walsh, a Flathead native and a veteran detective whose father had once been county sheriff, the records presented as many questions as the clues at his parents’ house did. Flanked by such jewels as Flathead Lake, Glacier National Park, and Whitefish resort, Hungry Horse is not a destination but a waypoint, offering little more than two gas stations, two diners, and two motels. Why, after such a deliberate drive west, did Pippin spend five days there? He took meals at the Huckleberry Patch, a tourist magnet that hawks huckleberry jams, pies, syrup, soaps, lotions, and saltwater taffy. He bought groceries—not expedition provisions but casual fare: sandwiches, apples, roast chicken, a couple of cans of Coke Zero. By all accounts Pippin hardly ever drank, yet in three days he bought a bottle of red wine, a bottle of white, a corkscrew, two cans of hard lemonade, and a premixed screwdriver. He placed calls to three credit card companies. Pippin purchased food in Hungry Horse each day between August 27 and 31, but he didn’t check into the Mini Golden Inns until the 29th. Where had he spent the first two nights? Detective Walsh canvassed the other motels, with no luck.

On the morning of August 31, Pippin left without checking out, leaving behind three pairs of pants, a laptop case, a sheet of camouflage netting, and car chargers for his cell phone and laptop. His computer has not been found. From the menu at Elkhorn Grill, where the most expensive breakfast item is $9.95, he racked up a bill of $23. Was Noah with another person? Walsh couldn’t find any waitresses who remembered him. At 10:45 A.M., Noah placed the lost call to his brother. And there the paper trail ends. After that, if what he told the Kerseys is true, he walked 64 miles on a dirt road to the Spotted Bear trailhead, then another 30 miles to the Chinese Wall, where he was last seen 15 days later.

Through the long winter and into the spring of 2011, as authorities waited for snowmelt to allow a search, a few clues trickled in. Then, in August, a Boy Scout troop discovered a shirt stuffed into a tiny creek, just a few miles south of where Pippin was last seen. Three weeks later I boarded a Chinook helicopter at dawn, along with 20 members of the Lewis and Clark County search-and-rescue team, the sheriff himself, three deputies, one ranger, one TV reporter, and a cadaver dog. Rosalie Pippin had posted on Facebook, “The sheriff asked us to ask any praying people to pray for him and the team 4 things: wisdom, discernment, guidance, and for A MIRACLE!”

We flew low beneath the rain clouds, meandered between the forested flanks of Moose Creek, then topped over a grassy ridge and saw it—the Chinese Wall—cresting overhead like a tsunami. We found the shirt within an hour and called for the dog, who arrived with her handler, a man with a potbelly and a gray walrus mustache. Heavy snow was falling. The dog sniffed the fabric without interest and lapped water from the stream. “If sheeda got a scent of cadaver, sheeda lay down, or sat,” the handler said mournfully. A deputy extracted the shirt. It could have been there for years, having grown a pelt of green moss. By now three inches of snow covered the forest floor, wildflowers bending beneath the load. “That’s what the good Lord sent,” said Sheriff Dutton, “so we can know what Noah went through.”

The next morning was sunny, and we broke into teams and combed the forest and boulder fields. “Thousands of hidey-holes out there,” said someone. If Pippin were injured or hypothermic or starved—or suicidal—he could have crawled into any one of them and died. Then again, if he’d walked 15 days debating whether or not life was worth living, this place—if anything—might have convinced him that it was. I belly-crawled into a cave and probed its corners with my flashlight. Maybe he was sitting on a beach in Zihuatanejo.

The foul weather prevented the searchers from reaching the spot where the trail left the wall, and ultimately the shirt could not be identified as Pippin’s. Bones pulled from caves were animal.

In October, a few weeks before the search team could launch a second mission, the Pippins dropped a bombshell.

“We’ve asked the searchers to stand down,” Mike told me. “We can’t for the moment tell you anything more about it, which is the same thing we told the deputies. We’re going to investigate it ourselves and find out if it’s actually credible. We’ve got information that Noah may be alive.”

In April 2004, Noah Pippin and Charlie Company, First Battalion, Fifth Marines, arrived in Fallujah just days after insurgents ambushed four American contractors, mutilated and burned their bodies, and dangled them from the Euphrates Bridge. The Marines fought a month of intense urban warfare. “It was gruesome,” said Major David Denial, Pippin’s platoon commander. “You’d kill people, and the dogs would come eat them at night.”

By all accounts, Noah Pippin was a good Marine. “He was very quiet and always could be relied on to get the job done,” said Gunnery Sergeant Tracy Reddish, who years after retiring is still called Gunny Reddish by his men. Trying to piece together Pippin’s life in L.A. and at Camp Pendleton, I’d flown to California to meet with Reddish and other members of his platoon. Whether charging an enemy position or scrubbing the toilet, Pippin never questioned an order. He was so averse to getting in trouble that when the men went out for beers in Oceanside in civvies, and were required to wear a flat-bottomed shirt or tuck their tails, Pippin did both.

Pippin’s respect for rank approached meekness. One time a senior Marine throttled Pippin with a leghold until his face was bright pink, and as the others hollered for Pippin to fight back, he gasped that he wouldn’t strike a corporal. His buddies determined that at 220 pounds he resembled a huge panda, and called him Man Panda. When Pippin revealed a fanatical love for Imperials, the cinnamon candies in MREs, his nickname evolved to Manda, the Elite Imperial Guard.

Although his gentleness invited teasing, it also won respect and affection. Adam Padavic joined the Corps when he was just 19, a kid from a small town in Illinois who wanted to be a cop like his mentor, and he remembers Noah as one of the only senior Marines who didn’t scream at the rookies or even raise his voice. “If you had a problem, you could go talk to him,” said Andrew Chavez, another grunt from Charlie Company. “He treated us like a big brother, looking out for us. He’d notice if someone was getting upset, and he’d say, ‘Calm down, it will be fine.’ ” Noah never drank, smoke, or chewed. In his free time at Pendleton, always struggling to maintain his weight, he would sometimes pack his gear and hike solo through the hills.

In February 2005, Pippin arrived for his second tour with Charlie 1/5, in Ramadi, another insurgent stronghold 77 miles west of Baghdad. The 215 men were housed in bunks at Camp Snake Pit, a long brown stucco barracks. Their mission was to drive convoys into the hostile city and capture or kill suspected terrorists. “Every house was considered unfriendly,” said Reddish. “We went in with arms loaded, took over the house, made sure nobody was a threat, moved them all to one room, broke down as soon as possible, and got out of there.”

Sometimes they found bad guys with guns and bombs, sometimes women and children huddled and wailing. Each day, Noah and his fellow Marines loaded into Humvees and trucks and motored toward town, knowing that at any second they could be blown sky-high. Charlie Company would eventually hit 38 improvised explosive devices. “Ramadi was like the Wild, Wild West,” said Reddish. “There was a shootout damn near every day.” The Marines were required to haul the corpses of insurgents they had killed into vehicles for transport to a base, to be identified and then handed over to Iraqi authorities. “Noah was straight-faced,” says Padavic. “He didn’t share emotions. He didn’t talk about killing or how many he’d killed.”

The Marine whom Noah admired most was Matthew Trigo, who had proven himself an exceptional warrior in his first two tours. The letter of commendation for his Bronze Star reads like a Hollywood script. Trigo takes out three enemy vehicles with his Mk 19 automatic grenade launcher. Trigo rushes into gunfire and digs a position with his folding shovel, then decimates the enemy. Trigo loads a single round into his machine gun and from 750 yards kills the driver of a moving car. But Trigo takes no credit for running into gunfire to drag his brothers to safety. “They were lifted by the Holy Spirit,” he told me. “I was just an ambassador. Best case: I save you. Worst case: I’m with my Father in Heaven.” A wall of muscle with a kind face and thin-rimmed eyeglasses, Trigo is a master of nine martial arts disciplines and was something like Charlie Company’s resident mystic. When he learned that Noah was estranged from his Christian upbringing, Trigo tried to coax him back into the flock.

“Bring on your Nietzsche,” Trigo told Pippin. “Give it your best shot. I’m just a Neanderthal Marine, but I’ve got truth and light on my side.”

“You’re my hero,” Noah told Trigo. “I want to be like you.”

“You can’t be nice to me and then hard on yourself,” said Trigo. Like Pippin’s family, Trigo had noticed Noah’s tendency to be self-critical. “I’ve lied, I’ve cheated. I kill men. I’m no better than you. Anything that’s awesome about me is awesome about you.”

Although most men in the platoon were not practicing Christians, Trigo led them in prayer. “Lord, unharden Noah’s heart. No man can hear the prophecy and be unchanged. Intellect without love is educated barbarism.” When I asked if his brother Marines resented his preaching, Trigo seemed surprised.

“They love me,” he said. “They love me.”

Of all the war stories told by Pippin’s fellow Marines, none was more devastating than what happened on June 16, 2005. It was about 115 degrees, and Adam Padavic climbed aboard his Humvee, lead vehicle, rear right seat, same as always. He had carved his initials on the steel bench with his pocketknife. Erik Heldt was up in the turret. As the engines roared, John Maloney opened the door. Maloney was Charlie Company’s veteran captain, and the men loved him. “The best man I ever knew in my life,” said Reddish. He was what Marines called a mustang—a grunt who’d risen to officer by proving himself. He wasn’t some ROTC boy who arrived in Iraq with a textbook, thinking he could tell combat vets what to do. “The best CO we ever had,” Padavic told me one day at his apartment in Los Angeles. “He really loved us.”

That morning, Maloney sent Padavic to another rig. “I’m riding here today,” he said.

They made enemy contact at the first house they stopped at. They were out of the vehicles, up on a rooftop, taking fire, returning it. Then back to the convoy to pick up the Army engineers. On the way back to camp, there was an explosion. The men leaped from the vehicles and broke into a house, blasted through the windows, emptying their magazines into the streets, hot brass shells flying into their faces. “Fucking chaos,” says Padavic. Suddenly Gunny Reddish appeared: “Where are the body bags?” Padavic didn’t understand. Why did they need body bags for these guys? “It’s not for them. Maloney’s been hit.” An IED had ripped open the fuel tank, the Humvee exploding and flipping in a storm of flame. When the fighting subsided, Reddish ordered his men away and brought in another platoon to hoist up the wreckage to find Heldt. He wanted his men to remember their brothers as they were in life.

As Padavic told me this story, he asked if I minded stepping outside with him so he could smoke. “I get kind of emotional,” he said. We stood beneath the eucalyptus trees and hazy L.A. sunshine. He stubbed his cigarette and tossed the butt. “Cap Maloney was a big guy,” he said, his voice cracking. He held his hands apart as if he were measuring a fish. “His body bag was only this big.”

That afternoon, Camp Snake Pit was miserable. Maloney and Heldt were dead, and three others were critically burned. Gunny Reddish remembers Pippin and Padavic sitting on the porch, a look of shock and grief on their faces. Reddish didn’t see the good in sitting around and moaning about it all day. What was done was done. They needed to take their minds off it. “Get your gear,” he ordered. “We’re going after the bad guys.”

Noah Pippin was the first man on the truck.

As I waited to hear from the Pippins last fall about the mysterious development, I traveled around Montana tracing Noah’s known whereabouts. Those who had seen him last were struck with a similar impression that he was saddled with a great emotional burden. I spoke with Bob Schall, who arrived at my Missoula home in jeans, a snap-button dress shirt, and a weathered Stetson. He recalled that after Pippin drained his coffee and walked off, Schall said to his friend, “That boy’s got some problems.” A few hours later, as the embers burned red, his friend turned to him and said, “You’re right.”

Schall figured the Marine had been through a divorce or something like that and was wandering the woods to clear his head. “That’s what I did after my divorces,” said Schall. “All of them!”

I drove to Hungry Horse from Missoula. It was a crisp fall day, cottonwoods bursting yellow on the banks of the river. At the Mini Golden Inns, Noah’s last stop, the proprietor, Kodye VanSickle, showed me Room 59, where the aquamarine carpets and blond furnishings and framed watercolors delivered on the marquee’s promise of Squeaky Clean Rooms. VanSickle was a delicate woman with gray hair, glasses, and sparkling eyes.

“He looked like he was carrying way too much,” she told me. “His exterior being was silent, like he could not express it to anyone.”

“What was on the interior?” I said.

“He was suffering,” she said. “The kind you have to do alone. He was searching for that connection that feels whole. I saw a dark shadow over his being.”

“Do you think he’s alive?”

She paused as if communicating with the ether.

“I’m not feeling that at all.” She cupped her breast. “I have a prayer heart—he’s in there. He’s one I wish hadn’t gotten away.”

She looked me in the eyes. “You were meant to be here, too.” Ms. VanSickle placed a medallion in my palm. Saint Jude. “The saint of impossible causes,” she told me. “You’re going to need this.”

From Hungry Horse I crossed the Rockies to Great Falls and looked up the Kerseys. “Not a day goes by when I don’t think about him,” Donelle told me as we sat in their living room more than a year after their encounter. “If I would have known that I was the last person to see him, maybe I could have convinced him to stay.” Vern Kersey has had a recurring dream in which he is searching for Noah in the woods. Finally he comes upon a tiny ramshackle cabin. He pushes open the door. Hunched over a rickety table, eyes hollow and face drawn in emaciation, like a ghost, is Noah Pippin.

It wasn’t until late October that Noah’s parents filled me in about their new development. They had received a phone call from a man named Miguel who told them he had read about Noah’s disappearance online. He said he had a niece who tended bar at the Loco Gringo in Tijuana. She had a boyfriend, a big American with a shaved head who looked just like the pictures Miguel had seen of Noah. Miguel said he had a friend named Carlos from the National Guard who had helped buy the man a fake passport. Miguel wanted to know if it could be Noah, and if so, was it safe for his niece to be dating this man. Was he a killer? Rosalie said that her son was not dangerous. Miguel said he would call back.

A month later, a credit card company called looking for Noah. Rosalie explained that he had been missing for more than a year. The agent said, “Well, someone’s been using this card.” The account had been opened at a department store in Iowa on August 15, 2010, two days before Noah arrived at his parents’ house in Michigan. Someone had been making purchases with the card—and paying it off—as recently as March 2011. The Pippins asked to see the statements but, maddeningly, were told that only Noah himself could request information about his account.

The Pippins were cautious but elated. Regaining hope that Noah was alive, the family was determined to respect his privacy, which was why they decided to investigate the lead themselves instead of going to the police. Mike Pippin canceled his upcoming trip to canvass small towns in Montana and planned a visit to San Diego instead. For the first time in a year, the Pippins believed they were within reach of finding their son.

Noah Pippin returned from Iraq in 2007 to a nation that was largely indifferent. “America is not at war,” said Gunny Reddish. “America is at the mall.” When the war began in 2003, 74 percent of Americans believed it was worth fighting. By the time Noah returned, that number had dropped to 33 percent, where it has remained ever since. An Iraq vet can surmise that two of three people he encounters don’t consider his sacrifice worth the trouble.

“You come back to this oblivion,” says Reddish, “and people don’t even care that you’re in a bad way, that your friends had to be identified from a dog tag in their boots. They say, ‘You did a great job. Now, how much money do you owe me this month?’ ”

A few weeks before his discharge, in March 2007, Noah visited home, and his parents threw him a 27th birthday party. Noah “has learned that he is more anxious than most in social situations and has a tendency toward paranoia and obsessive thinking,” Rosalie wrote to a friend at the time. “Yesterday he described to Josiah that his ‘demons’ are beginning to come back (i.e. depression, anger, anxiety, etc.) and he lightly told Josiah it’s time for him to leave.”

“He looked war weary, subdued and overall just tired, like many vets I’ve seen since,” wrote his friend Patrick McDonnell, who was preparing to deploy to Afghanistan. “It may have been a combination of his experiences overseas and the amount of growing up since we last saw one another, but I could tell at least a little part of my childhood friend wasn’t there in his eyes anymore.”

When Noah returned to Pendleton, his closest buddies had been discharged. “The Marines are allowing him to stay in the barracks until April 21 but he does not know what he’s going to do after that date,” Rosalie wrote to a military support group. “Does anyone in your group have experience with how to help a son transition to civilian life?”

Noah left the Marine Corps with very little savings. After living in his car for six months, he was hired by the LAPD. His training salary didn’t cover all the gear and uniforms, and the California National Guard was offering a hefty incentive. For a Marine, the National Guard was a step down, but he needed the money. “I ended up joining the army (lol),” he wrote to Marine Andrew Chavez, “and they gave me a 20,000 dollar bonus in ’07 for going into the National Guard (lol) as an infantryman.”

While he waited for the payment, Noah lived in his car in the alleys near the police training center. With his military background, he was made a squad leader. But the honor only caused more anxiety: it was stressful enough to arrive an hour early to use the shower. The cadets teased him because sometimes he smelled like a homeless man; they didn’t realize he actually was one.

Eventually, Noah rented a single bedroom in the back of an old house on the southern fringe of Koreatown, on a barred-window stretch of Crenshaw Boulevard, one of the city’s busiest arteries. The landlord lived in front and spoke no English. Noah shared a bathroom and kitchen down the hall with some other cops. He furnished his room with an air mattress, a single chair, a television, and a small table for his laptop. There was no closet, and his few possessions were scattered in boxes on the floor. For the first year or so he ate out or ordered in, until his parents shipped him a Crock-Pot from the Sears catalog.

As a probationary officer, Noah was assigned to the crime-ridden Southeast District. Figueroa Street is dotted with storefront churches, payday-loan merchants, places to send money south of the border, and ratty motels. At night it’s populated by streetwalkers and crack dealers.

Noah felt like he was arresting people for the same misdemeanors day in and day out, only to see them resurface a few days later. Instead of fixing a busted system, he was enabling it. Noah complained that some of the officers who trained him were lazy. They would respond to a call at the end of their shift, and if the senior officer didn’t want to do the paperwork, he would tell the citizen to file it in person at the station. “Noah is a black-and-white guy,” said his father, “but the LAPD was gray.”

Although he expressed his unease to his family, Pippin’s code of honor prevented him from publicly speaking ill of his fellow officers. “In Noah’s background and way of thinking, he still owed loyalty to his peers no matter what they did wrong or how those things affected him,” said his brother Caleb. “That’s an idea and pressure that was placed on him mostly due to his military background.”

Just a few months into his rookie year, Noah was called up by the National Guard to deploy to Kosovo, but he tore his ACL during a training exercise. After surgery, the Army paid for a physical rehabilitation program in Los Angeles and gave him a desk job in a downtown skyscraper, in the security office of the Army Corps of Engineers. His boss, Jeffrey Koontz, is an avuncular, bald-headed man who patrols his windowless cubicle in combat fatigues and fields phone calls by punching the speaker button and hollering, “Sergeant Major!” When Pippin arrived for his first day on the job—also bald, also in fatigues—everyone joked that Sergeant Major had hired his own son.

“I’d be proud to have Noah as a son,” said Koontz. He remembers Pippin as quiet, earnest, and unfailingly polite. “We had some great conversations,” says Koontz. “He was a really deep thinker, very analytical, not a typical cop.”

Noah commuted in camo in his Corolla, up Crenshaw and across Wilshire. By parking in the five-story garage, it was possible for him to spend a day at work without ever going outside, or for that matter looking out a window. He arrived with his PT bag and worked out in the building’s gym. Sergeant Major often invited Pippin to lunch, but Noah declined, typically eating from a brown bag by himself in the break room. He never talked about the war; Koontz never even knew he’d been in Iraq. A woman in the office found the stoic GI dreamy and would alter her route to linger at his desk, but he never so much as asked for her phone number.

Near the end of 2009, when Noah left the skyscraper, Sergeant Major offered him a permanent job. For several months he left follow-up messages, but Pippin never called back.

Noah Pippin never sought treatment for, nor was he diagnosed with, post-traumatic stress disorder. He once told his parents that he was worried that any sort of medical treatment—even for the hearing loss he suffered—might rule out future jobs in the military or law enforcement. Nonetheless, Pippin’s behavior after returning from Iraq appears to fit the symptoms, which often include the reexperiencing of combat, avoiding intimacy, and withdrawing from friends and family. Once during training for night-combat operations with the LAPD, in which he and his fellow cadets had to identify paper pop-ups as either threats (a man with a gun) or civilians (a woman with a baby), Pippin screamed “Contact front!” and in a barrage of cursing emptied his magazine at the target. In an exercise where cadets practiced arresting one another, Pippin discovered a gun on his “suspect” and knocked the handcuffed man face-first onto the ground. He was reprimanded but deemed fit to continue his training. I asked an LAPD spokesman if Officer Pippin had ever been evaluated for mental health issues, and he told me that such personnel records were confidential. Pippin’s commander at the National Guard said that Pippin and all guardsmen were regularly evaluated for physical and mental health.

Diagnosed or not, the war has taken its toll on the men of Charlie 1/5. During my visit with Gunny Reddish, he told me that seven years after Ramadi he still gets phone calls, sometimes in the middle of the night, from young men—scared, drunk, about to do something stupid. He starts out gently, telling them to put down the bottle, take a deep breath, calm down. If that doesn’t work, he reverts to drill sergeant, tells them to shut the fuck up right now or he’s driving halfway up the state of California to put his boot in their ass.

Pippin never made such calls to Reddish or any of his other Marines. Indeed, several living in the L.A. area had not even known that he was close by. Pippin told his mother that some of his Marine buddies would get together, but because he’d gained so much weight after his injury, he was embarrassed to meet them. He became isolated. Noah did not keep in touch with his classmates from the academy, nor did he become close to officers from the Southeast Precinct.

When Pippin wasn’t at work or the gym, he was at home, reading books, playing video games, and sinking deeper into his own mind. When I learned from his brother Josiah that Noah used the online moniker “benx6444,” I searched and found a long record of his writings and activities—perhaps the most revealing history of a man who kept largely to himself. He logged hundreds of hours gaming, his favorites being Warhammer 40,000: Dawn of War (106 hours), Command and Conquer (89 hours), and Jagged Alliance (68 hours).

The site he apparently visited most was the Skeptics Guide to the Universe, a forum dedicated to “the paranormal, fringe science, and controversial claims from a scientific point of view.” In the year leading up to his disappearance, Noah posted there 2,774 times. He indulged his passion for speculation and history and philosophy: “You wake up on a stretch of beach outside of Rome [in 10 B.C.] How do you earn your living? What could you contribute? Build? Manufacture? What would be the easiest profession to take on/make to become rich?”

On a site dedicated to the Austrian economist Ludwig Von Mises, Noah split the sort of hairs generally reserved for graduate seminars:

Is there really a contradiction here between what Mises says about the impossibility of planning an economy due, in large part, to the unpredictable nature of human action and Mises’s seeming implicit assertion that he has, according to the reviewer, “a tool for distinguishing one event from another, and for judging when they are the same.”

In the Skeptics’ forum, Noah showed increasing cynicism toward his profession. He quipped, “Cops = glorified janitors.” In a thread offering the glib career advice “ROTC > Full Scholarship > Job > $$$$ > Live somewhere else > Shoot people,” benx amended the final line to “Order other people to shoot people.” To a young man seeking advice on love, benx replied, “It doesn’t exist.”

Pippin’s online writings reveal a man slipping into the rabbit hole of his own mind. Instead of tackling the big questions, Pippin wove ever more complicated defenses of the smallest points. On GameSpot.com, he employed his rhetorical gifts to savage a review of a video game:

Joe Dobson’s whiny review of ‘Army of Two’ isn’t so much about the game as it is about his POLITICAL VIEWS on a subject and how he feels the game treats his political views. … Dobson can’t handle someone else’s perspective, or an interesting dialogue about the effectiveness of State Militarys vs Private ones. He’s already made up his mind, and anyone attempting to even talk about this issue without his stamp of approval, or who isn’t in lockstep with him get’s their game shutdown. What a clown.

In November 2009, Pippin bought an expensive hunting rifle. Taking it to a shooting range was one of the few activities he remained passionate about. “It’s so freakin’ cool!” he wrote. “It’s not like ordering a burger at McDonalds or buying furniture. When you walk into a firing range, you suddenly become aware that your fellow Man is there with you. It’s kinda scary until you look left and right and see that … it’s cool, ya know? You can trust each other.”

He wrote that after mastering his rifle at the range, he might like to try hunting big game like bear, elk, and deer. Another poster mentioned that hunting black bear was illegal in Montana. Sometime thereafter, Pippin requested the hiking pamphlets for Yellowstone and the adjacent Gallatin National Forest. This was the closest link I found between Pippin and the Bob Marshall. But as for the rifle, instead of carrying it into the woods, Pippin left it in the basement of his parents’ house.

Miguel called again in October. He told the Pippins that Carlos’s cousin, an illegal immigrant, and Noah were holed up at a cheap motel in El Cajon, a San Diego suburb. He said that Noah was holding a job in the States, crossing the border to see his girlfriend. Miguel said that one day, while the illegal roommate was at work, Noah invited his buddies over for a party. When the cousin returned, everything had been stolen. Since he was illegal, he couldn’t call the police. He was a real hardworking guy, said Miguel, just trying to get ahead, to support his family back in Mexico, and it was a real shame that because of Noah he’d lost everything.

The Pippins grew suspicious and asked Miguel for his phone number, but he declined. They asked if he had a Facebook page, and he said yes. They saw that it had been created that same day. The photo of Miguel was one easily available online. Feeling like they were in over their heads, the Pippins finally revealed their conversations to Detective Walsh, who told them without hesitation that the calls were part of a common scam used to shake down families of missing persons. “I see this kind of thing every day,” he said. The phone calls from Miguel ceased.

Walsh also subpoenaed the credit card records. He didn’t give much credence to the theory that Pippin was alive and shopping. More likely, someone had found Noah’s wallet and had been using the card. As it turned out, the hope offered by the credit card agent was false; what appeared to be recent activity was actually just paperwork blips caused by the transfer of Noah’s account from one bank to another.

“Not a day goes by when i don’t think about him,” Donelle told me more than a year after their encounter. Vern Kersey has had a recurring dream in which he comes upon a tiny cabin. hunched over a rickety table, face drawn in emaciation, like a ghost, is Noah Pippin.

Then, just as the case seemed to turn cold once again, another witness came forward. In October, Steven Pierce was driving near his home in Kalispell when he heard the story on the radio about the missing Marine. By then, a year had passed since his hunting trip in the Bob. Noah—that biblical name—rang a bell. Pierce called Detective Walsh.

On the evening of September 12, 2010, three days before Noah had last been seen by the Kerseys, Pierce had hauled his trailer along the 64 miles of dirt road from Hungry Horse to the campground at Beaver Creek on the Spotted Bear River. He led the horses off the trailer and fed them some hay. He noticed the man at the adjacent site with no vehicle and said hello.

Pierce remembers the stranger as none too friendly. Pippin kept his back turned when Pierce started asking questions and said curtly that he’d hiked in from Hungry Horse. Seeing the fatigues, Pierce asked if he was military, and Noah told him he was a vet.

“You been over in Iraq?”

“Got back a little while ago.”

“I was in Vietnam,” said Pierce, hoping to break the ice. “Navy.”

Noah didn’t answer.

“If you’re going hiking in these parts, you need a gun,” said Pierce. “Do you have one?”

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Just a .38.”

“That ain’t much to stuff in the face of a grizzly when he’s chewing on your foot.”

“It’s all I got.”

“Where you from?”

“Southern California.”

Pierce surveyed Noah’s camp: a one-man bivy tent, a lightweight sleeping bag, a hunting knife, a small backpack, a plastic jug. It appeared to be all his worldly possessions. No provisions that Pierce could see.

“You’re obviously not a hunter,” said Pierce. “What are you doing out here, anyway?”

Pippin admitted that he’d had some financial problems. The only way to get out from under them, he said, had been to join the National Guard for the signing bonus—which he’d already spent—and now he was locked into more duty. He told the hunter he didn’t want to go back to Iraq or Afghanistan. He was adamant about it.

This was a drastic break from what he had told everyone else. Like so much in the case of Noah Pippin, it just doesn’t add up. If his financial problems were paramount, his parents, who had often encouraged him to finish college with the GI Bill, would have helped him make the transition. If his chief concern was avoiding a fourth tour, simply remaining in his Guard unit would have afforded him more than a year to figure out a solution. Maybe he felt that he had checkmated himself: by quitting his job, he had no choice but to redeploy, but now 12 days alone in the woods had brought the fatal clarity that he couldn’t go back to combat, and neither could he face the shame of having failed to report.

Two things are clear. First, the date was September 12, a full two days after he was legally required to report for drill, a fact that surely weighed heavily on a Marine who valued honor above all. The man who found sanctuary in the rules had, for the first time, broken them. Raised in black and white, saved or damned, he could not help but consider himself one of the defective. Second, as he grappled with these life-and-death decisions, he did so without the parents, brothers, and Marines who loved him.

The two war veterans regarded one another at that campground picnic table.

“Are you AWOL right now?” said Pierce.

Noah wouldn’t face him.

Pierce asked again.

“Yes, I’m AWOL.”

“That’s not good, son,” said Pierce. “Marines don’t do that shit. We don’t cop out on our country.”

Noah turned his back and said, “I’m going to bed now.”

“There’s bad weather coming,” said Pierce. “You gonna be all right?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You know the trails out here?”

“Yes, sir.”

Pierce returned to his truck and brought Noah a couple of granola bars and an old map. When he set out on the trail in the morning, he didn’t notice whether or not Pippin was still there.

Where is Saint Jude when we need him? Kodye VanSickle at the Mini Golden Inns prays the novena to the patron saint of lost causes, of cases despaired of. As of February, Pippin’s whereabouts were still a mystery. Beset by nightmares, Vern Kersey has volunteered himself for the next search mission, sure he could lead them to the right spot. Detective Walsh retired before solving the case, but during his final month as a police officer he went hunting, and of all the grounds he could have chosen, he picked the Spotted Bear River, where he retraced Noah’s path; he saw a couple of bucks but didn’t take a shot. Gunny Reddish is retired, too, and when he fields those midnight phone calls from his men, he’s glad he spared them the horror of what lay beneath that incinerated wreck in Ramadi, a vision he’s never been able to shake. When I left the Pippins in November, they prayed with me, asking for an end to this, hoping that if Noah is alive he might contact them. The war is officially over now, but it wanders our woods, haunts our dreams, and occupies our prayers.

On a Sunday afternoon in Los Angeles, back in October, I got a call from Matthew Trigo. I drove north three hours through the high desert and found him in a spacious home with a green lawn, kids on bikes, afternoon sunshine on the streets. While we talked in his backyard, the distant sun dropping slowly as the hours eased by, his three children crawled onto his lap and he twirled them with his Popeye arms as if they were kittens. Trigo told me he is on disability for his wounds, has trouble holding a job, and doesn’t use the phone much. “I’m a believer in being completely present in the moment,” he said. If a call distracts him from his children, he ignores it.

“I wish I was still there,” he told me. “When you hear another friend is dead, you think: I should be there.” I asked how he reconciled the demands of war with the tenets of his faith: Thou shall not kill and Turn the other cheek. He spoke of the Old Testament warriors, of David slaying Goliath, of Samson destroying a thousand enemies with the jawbone of a donkey. “I’m a hypocrite and a sinner,” said Trigo. “But we are redeemed by the blood of Christ.”

Across this landscape of believers, Pippin’s knell rings in biblical tones. His Father created a Garden, but Noah Pippin walked out of it, then found the fallen world impossible. While Trigo is able to navigate the jagged terrain between Camp Snake Pit and here, Pippin has not found his way home. Trigo told me that the last he heard from Noah was a few years back, when Trigo agreed to serve as a reference for the police job. He and Noah were messaging, Trigo’s wife doing the actual typing, and Noah tapped in the same lines he used in Iraq. “You’re my hero,” Noah wrote. “I want to be like you.”

“He was searching for peace,” Trigo speculated, “and couldn’t find it, so he went to wilderness, where there is nothing to rebel against. You can’t rebel against nature.”

I asked Trigo if the police department had ever called him.

“No, they did not,” he told me. “I was waiting for them. I had a lot of good things to say about him.”

If you have any information concerning the whereabouts of Noah Pippin, please contact the Lewis and Clark County Sheriff’s Office at 406-447-8293.