The Gerlache Strait looks exactly as I imagined Antarctica would: Snow spills to the edge of the passage from the jagged landscape lining either side. The tops of icebergs rise from the flat, dark water like stiff peaks of beaten egg whites; the ice just beneath the surface glows turquoise. The air hangs soft and gray, and by the time the ARSV Laurence M. Gould rounds the southern tip of Anvers Island and enters Arthur Harbour, a light snow is falling.

Through the thick flakes, a handful of Monopoly-size buildings materialize. Figures in bright orange suits amble to the edge of the dock as the ship pulls in. Some grab the research vessel's towlines; others spot the first snowball flying at the exact moment I do. It comes from the stern, where marine biologist Kim Bernard has dipped into a cardboard-box arsenal. The other side quickly retaliates, and soon the residents of Palmer Station—both current and incoming—are locked in battle.

Palmer is the smallest of the three year-round U.S. research stations in Antarctica and the only one on the West Antarctic Peninsula. It's also the only station without an airstrip. Reaching Palmer requires a four-day voyage from Punta Arenas, Chile, on the Gould. The vessel plunges south through the Drake Passage as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the largest current in the world, sweeps through the same narrow channel barreling east.

Just before I left the United States for Chile, Hugh Ducklow, the director of a long-term ecological research project at Palmer, told me that the station's location, chosen in 1965 for its convenience, turned out to be a stroke of great scientific luck. "For decades, nobody had any idea about climate change," he said. "Now we find ourselves at the very spot where it's happening most rapidly."

Over the past 50 years, the average air temperature increased 6 degrees Fahrenheit along the West Antarctic Peninsula, unlike that farther north or south. Scientists have also documented stronger surface winds, cloudier skies, more snowfall, less ice, and warmer ocean water—all adding up to profound changes in the polar ecosystem. Because that ecosystem is relatively uncomplicated, scientists can detect and establish the significance of these changes more easily than, say, in a coral reef or even in a forest in the U.S. By studying climate change at Palmer, Ducklow says, "we can figure out rules of ecosystem response elsewhere."

Thanks to a fellowship from Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory, I've come to document something too: station life. I begin my research in the galley with a penguin-shaped sugar cookie, then go on a tour. It doesn't take long. Pretty much everything is located in two buildings sandwiched between a glacier and the Southern Ocean. A lone street sign points toward Denver (7555 miles) and the South Pole (1744 miles). Three weeks here, I think, could go by very slowly. Instead, they fly far too fast.

"Man overboard!" Katharine Coles is pointing at me from a rubber zodiac as I bob in the 32-degree Fahrenheit polar waters. I'm wearing an extra-large neoprene survival suit, which, because I'm only five foot six, bunches in giant folds around my limbs. I feel surprisingly, pleasingly, warm. Lily Glass, Palmer's boating coordinator, tells Coles to drive away from me; I awkwardly swim to a chunk of ice and cling to it for dramatic effect. Then Glass talks Coles through a Williamson turn, a rescue maneuver that brings the zodiac back to the point where I "fell" out.

Glass grew up on the water, pulling lobster pots in New England, and learned her way around an engine after buying a 1971 Volkswagen bus. But mostly it's her unruffled calm, honed while teaching high school science in Massachusetts and Mongolia, that she brings to Boating II—a mandatory class for anyone who wants to pilot a zodiac onto the Southern Ocean. At Palmer, that's pretty much everyone.

"Some of my favorite days are the crappiest out on the water because you have to be that much more focused," Glass says. "And it's those days that really make you appreciate weekends, when you can turn off the engine and not go anywhere." On a Sunday with exceptionally clear blue skies, people pile into zodiacs to chase reports of breeching humpback whales. Coles—who is Utah's poet laureate and, like me, applied for a grant to visit Palmer—doesn't have to go searching for wildlife. Twice a penguin jumps in a zodiac with her.

64°46'S, 64°03'W

1. Biolab with Galley, Offices, Labs, Aquarium, and Dorms

2. GWR Building with Garage, Power Plant, Warehouse, Store, Clinic, Dorms, and Bar

3. Carpentry Shop

4. Earth Station with Satellite Link

5. Fuel Tanks

6. Terra Lab

7. Milivans Containing Hazardous Waste

8. Dock

9. Milivans Containing Frozen Food

10. Boathouse

11. Zodiac Parking Lot

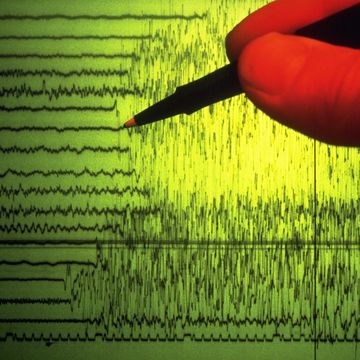

During the Austral Summer, which stretches from roughly November to February, there is no real darkness in Antarctica, just twilight. The sun is still shining brightly at 9:30 on my first Friday night. Behind the BioLab, graduate students are setting up an ocean-acidification experiment in a marine tank; in the tank next to that, six people are soaking in the station hot tub. The sound of Cake floats over from the Terra Lab, where an array of instruments constantly monitors seismic activity, atmospheric radionuclides, and electromagnetic waves generated by lightning strikes around the globe. Brian Nelson, the lab's technician, is leading another suite of instruments in a "Terra Jam": Palmer's band is practicing for open-mike night.

Alice Alpert sits on the edge of Bruiser, the wooden work platform mounted across the zodiac, and dangles her brown XtraTuf boots over the water. Alpert's flotation jacket easily doubles her small size. Despite clumsy insulated rubber gloves, she adroitly cocks the latex band on a gray plastic Niskin bottle so that both ends remain open, and lowers it with a winch 10 meters into the Southern Ocean. Then she fires a weight down the line to snap the ends shut, capturing water.

Researchers have been methodically sampling the ocean here for the past 20 years, and the data reveals changes at the very bottom of the marine food web. As stronger winds churn the water column, for example, phytoplankton are pushed deeper, away from sunlight, so they bloom far less often. These winds also upwell deep, carbon-dioxide-rich water, limiting the amount of CO2 the ocean can absorb from the atmosphere—a process Alpert's team is trying to understand.

I'm tasked with operating the winch to bring the Niskin bottle to the surface. Only, distracted by the line coiling at my feet, I look away at exactly the wrong moment and the bottle hits the top of the winch with a thud. I click the button to try to lower it. No power. The team takes it in stride, heading back to exchange Bruiser for Wonderbread, which has a hand-cranked winch. Later, someone gives me the blown fuse as a souvenir, saying: "Welcome to science."

The Southern Ocean can be glassy and smooth or whipped by 50-knot winds and roiling with giant swells. Because these conditions change within minutes, safety at Palmer is taken very seriously. Whenever a group of boaters signs out a zodiac, they give themselves a name, which may or may not reflect the purpose of their trip. Like Moe at his tavern on The Simpsons, a communications officer dutifully repeats this name over the two-way radio every time crews check in—which is often. During my stay at Palmer, names included Going Viral, Bromance, Sir Ernest Shackleton, Apollo 25, and Hold My Beer and Watch This.

Sleek and yellow, the Slocum Glider autonomous underwater vehicle resembles a torpedo. When I peer inside, it looks much less ominous. Rows of D batteries line the aft end, and I can see all the way through to a buoyancy pump. The glider is propped up on a counter in the lab while Travis Miles, a graduate student at Rutgers University, dismantles it. He's trying to figure out why the leak-detect sensor went off when the team deployed the vehicle. "Being down here has been a whole new world of beta testing," he says.

Once the problem is fixed, the team plans to send the glider across a deep-sea canyon near Palmer. Such canyons allow warm, salty water at the bottom of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to flow up onto the continental shelf. Historically, that's been a boon to marine life, delivering heat and nutrients that stimulate food supplies. Only now they appear to be delivering way too much.

The real engine of the Antarctic ecosystem is the Southern Ocean: Water holds a thousand times more heat per unit volume than air does. Over the past 50 years, water along the peninsula has warmed significantly. Ice transfers this heat to the atmosphere: The midwinter air temperature has risen 11 degrees Fahrenheit, five times the average global increase. The winter ice season has lost 83 days, effectively disappearing.

The gliders, scientists hope, will track how greater volumes of this warm, deep water are being swept onto the shelf. Unlike humans, who are limited by weather and their own endurance, gliders can slalom through the Southern Ocean day and night for hundreds of miles. They move by changing buoyancy: pulling a coffee cup's worth of water into the nose, then pushing it back out again.

Miles shows me the air bladder in the glider's tail, a balloon about the size of an airplane pillow. When it inflates, the tail lifts out of the water so an iridium phone can call Rutgers for the glider's next set of instructions. "If we see something interesting," he says, "we can adapt how we fly the glider and hypothesize as we go."

"Birders, this is Dragnet." Silence ensues. Alex Culley, a researcher from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, tries again. He's in a zodiac, sampling for marine viruses. There are a billion in every liter of seawater, and he's trying to tease out their role in the polar ecosystem. Another long pause, then Glass radios from the station: "Dragnet, this is Lily. They have to hike up a hill in order to get reception."

"Thanks, Lily. Actually, maybe you can answer this. We've got a chinstrap [penguin] that's jumped onto our boat. Please advise."

>

POLAR SCIENCE >>>

Kim Bernard and Carolina Funkey, researchers from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, work quickly in the back of the zodiac. Bernard holds the rope attached to a tow net taut while Funkey ties a knot with the slack. I throw three buoys over the side and radio Palmer with our next destination.

"Psycho Krillers headed to Station E. Copy," the comms officer radios back. Bernard pushes the throttle forward.

As our name implies, we're fishing for krill, shrimplike crustaceans that are the favored food of everything from penguins to whales and some types of seals. Over the past several years, catching krill has gotten tougher. On our first pass, we net only five. "Antarctic krill rely very heavily on sea ice for their life cycle," Bernard says in a lilting South African accent, which she also uses to great effect in the station band. "Because the sea ice is declining, they have less and less area where they can survive."

Krill also depend on phytoplankton, but they're not good at grazing the small cells that now dominate the algal community. Other zooplankton are. "One thing that's ringing all the alarm bells is the fact that salps are moving in and taking over," Bernard says. Like creatures from a bad B movie, salps pulse through the water column, trapping food in a mucous mesh. They're voracious eaters, but of little nutritional value themselves. If they run into a phytoplankton bloom, they just eat until they die.

Penguins are engineers. Each spring, they meticulously build nests of rock—some comically high—then take turns lying atop them for weeks. I didn't fully appreciate this until I stepped out of a zodiac onto Torgersen Island with the Birders—the only group that never changes its name. The three Birders weave among colonies of Adélie penguins, careful to steer clear of the occasional elephant seal.

Unlike the other scientists, the Birders work outside Palmer's main lab building in a faded red tent stuffed with Clif Bars and yellow weatherproof notebooks. When they arrive at study sites, on islands near Anvers, they strip off their orange Mustang suits to reveal head-to-toe khaki. After stripping off my own Mustang suit to reveal more neon orange, I learn why: Khaki doesn't scare the birds.

Skuas are crafty. I watch one of the large brown birds saunter up to an Adélie penguin colony. It has a nonchalant air, but the penguins know better. They extend their necks, swinging their heads from side to side for a better look, and chatter angrily. Stock still, the skua waits them out. One of the penguins shifts on its rock nest a little too far and the skua's mate swoops in for its egg.

I'm appalled. It's like seeing a character from Happy Feet picked off. "They're predators, so they get a bad rep," says Jen Blum, a field biologist at Palmer for her sixth season. "I love that they're ballsy." But in the real-life skuas-versus-penguins plot, neither are thriving.

Adélies are hard-wired to return to the same exact spot to breed, at the same exact time, year after year—regardless of krill supplies or spring snowstorms that flood their nests. In the 1970s there were 15,000 breeding pairs on the islands surrounding Palmer; now there are fewer than 3000. "The skuas are following the same trend as the penguins," Blum says.

The Birders census skuas, too, and as Blum measures an egg, the bird's mate dive-bombs her, wings outstretched like a B-57. It lands on her back, then moves up to her head, where it tries to pull off her hood with its beak. Blum is unperturbed: "That's why I wear a hood."

Danger Crevasses Stop! The sign at the top of Marr Glacier is surrounded by ominous black flags. Roped hip to hip, we walk right by them. Palmer's Glacier Search and Rescue (GSAR) team has gallantly offered to drop me into Marr's yawning maw. And then, I hope, pull me back out again.

To get to the glacier, we first have to walk to it. This wasn't always the case. In 1967 the base of the glacier came right to the station. Since then it has pulled back 1600 feet. In fact, 87 percent of all glaciers on the West Antarctic Peninsula are receding. At the end of November, I lost shoe crampons in the glacier as my feet sank through a thick layer of snow. Now, in late December, it's like hiking over the crust of freezer-burned ice cream.

When we reach a manhole-size opening, Paul Queior sets up a belay system, twisting three 9-inch screws into the ice. Palmer has so few staff that they all take on multiple roles: Queior is an IT specialist, but he's also an EMT on the trauma team and leads GSAR. He talks as enthusiastically and knowledgeably about the station's bandwidth as he does about intubating patients and climbing Kilimanjaro.

At Palmer, this isn't particularly unique. "You learn immediately that it doesn't matter what someone's job is—they're brilliant and they're capable," Queior says. "You know you better not prejudge because you'll find out that wastie"—waste management specialist—"has two degrees and can beat the pants off you in a debate."

Ted McKinley, the station's carpenter, descends into the crevasse first, the very top of his wool hat disappearing into the ice. His voice is tiny when we next hear it: "Okay, can't do plan A. There's nothing to anchor to on my left. Going to my right." He finds a good hold and gives the all-clear.

Now it's my turn. Nestled firmly in my harness, I'm lowered down the chimney-like hole until I find footing on an ice bridge. The crevasse yawns, bottomless, below me and as far as I can see in either direction—intensely blue and pocked with cottony snow and sheets of icicles. It's breathtaking.

As I settle into an alcove next to McKinley, my feet hanging over the abyss, I think about something Tracey Baldwin, Palmer's science support manager, told me back at the station. Marr Glacier used to calve into the ocean with a splash, sending giant waves across Arthur Harbour. Now, as she sits in her office, she can still hear the glacier calving, only it sounds like thunder—because it's receded so far it's calving on land.

As a vegetarian, I ignore the chicken bucket and instead scrape my food scraps directly into the baby grinder. The station garbage disposal, presumably named for its size, sends them to a masticator where they're ground up, mixed with wastewater and copious salt water, and pumped into the harbor for the tide to sweep out. The rest of Palmer's trash has to follow the "leave no trace" principle of the Antarctic Treaty: Pack it in, pack it out. There are no landfills in Antarctica.

Jed Miller is Palmer's wastie. His domain comprises a series of rusting metal shipping containers marked with hazard symbols and lined with steel drums. Solid waste—including poultry, lest it introduce an avian disease to the ecosystem—is shipped back to Chile. Hazardous waste, such as lab chemicals, goes all the way to Washington state. "My boss, the head of waste management, says that our department is not supporting science," Miller says. "We're here to uphold the Antarctic Treaty—that's what we care about. We care about making this place clean and pristine."

Miller started working in Antarctica 12 years ago and has cycled through all three U.S. stations—winter-overing twice. When I ask if he'll be back next year, he says his last season was supposed to be two years ago. Glass tells me that's not unusual. "I could potentially never be done with Antarctica," she says. "Part of me sometimes thinks I want a regular life, but then I talk to folks back home who have that 9-to-5, the commute, and all of the above, and I realize if I were to do that I'd be wanting to come back here pretty quick."

"Attention, Palmer Station. There's a leopard seal attacking a penguin in Arthur Harbour." As the alert crackles over the PA system, everyone in the bar grabs a beer and rushes onto the balcony to watch.

SAVED! I think. Glancing over the edge of the gravel dock, I can see the water is filled with sharp chunks of brash ice. Jumping into that would be like leaping into a half-blended margarita, blades and all. It would be crazy.

Only, by lunchtime, the brash has all blown back out. I'm told to go put on my bathing suit.

The polar plunge is a ritual at Palmer. Mostly, it's done as a farewell to the departing Gould—but people also plunge for more spontaneous reasons, such as the initiation of visiting journalists. As polar fleeces and wool hats fall to the ground around me, their owners soaring off the dock in alternating swan dives and cannonballs, I'm torn between getting it over with and postponing the inevitable: Then, with a final glance at the nearby outflow pipe, I decide to go for it.

The hollow rubber fender is firm under my bare toes as I climb up and bounce a few times experimentally. It's freezing in the air, too, so I assess the water, aim for an opening between the few remaining pieces of ice, and leap. For a split second, time stops, suspended—then splash. It's cold! I swim faster than I ever have for the rusted ladder leading back up to the dock, then run 80 yards to the station hot tub. It's already crowded.

I slip into the water between Palmer's logistics coordinator and one of the Birders. The tank, like the Southern Ocean we just jumped into, contains a cross section of life along the West Antarctic Peninsula—representatives of the entire station ecosystem. Steam rises around us. My short, wet hair, meanwhile, freezes into crunchy icicles. The low rumble of elephant seals challenging each other floats across the harbor. Beyond my shoulder, Marr Glacier towers over the still blue water, then calves, thundering. There is no splash.