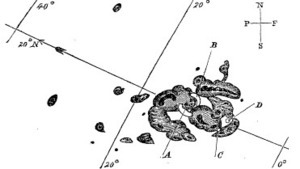

Noon approached on September 1, 1859, and British astronomer Richard Christopher Carrington was busy with his favorite pastime: tracking sunspots, those huge regions of the star darkened by shifts in its magnetic field. He projected the Sun's image from his viewing device onto a plate of glass stained a "pale straw colour," which gave him a picture of the fiery globe one inch shy of a foot in diameter.

The morning's work went as normal. Carrington patiently counted and charted spots, time-lining changes in their positions with a chronometer. Then he saw something unusual.

"Two patches of intensely bright and white light broke out," he later wrote. Carrington puzzled over the flashes. "My first impression was that by some chance a ray of light had penetrated a hole in the screen attached to the object-glass," he explained, given that "the brilliancy was fully equal to that of direct sun-light."

The astronomer checked his gear. He moved the apparatus around a bit. To his surprise, the intense white patches stayed put. Realizing that he was an "unprepared witness of a very different affair," Carrington ran out of his studios to find a second observer. But when he brought this person back, he was "mortified to find" that the bright sections were "already much changed and enfeebled."

"Very shortly afterwards the last trace was gone," Carrington wrote. He kept watch on the region for another hour, but saw nothing more. Meanwhile, the explosive energy that he had seen rushed towards him and everyone else on earth.

Better than batteries

It hit quickly. Twelve hours after Carrington's discovery and a continent away, "We were high up on the Rocky Mountains sleeping in the open air," wrote a correspondent to the Rocky Mountain News. "A little after midnight we were awakened by the auroral light, so bright that one could easily read common print." As the sky brightened further, some of the party began making breakfast on the mistaken assumption that dawn had arrived.

Across the United States and Europe, telegraph operators struggled to keep service going as the electromagnetic gusts enveloped the globe. In 1859, the US telegraph system was about 20 years old, and Cyrus Field had just built his transatlantic cable from Newfoundland to Ireland, which would not succeed in transmitting messages until after the American Civil War.

"Never in my experience of fifteen years in working telegraph lines have I witnessed anything like the extraordinary effect of the Aurora Borealis between Quebec and Father Point last night," wrote one telegraph manager to the Rochester Union & Advertiser on August 30:

The line was in most perfect order, and well skilled operators worked incessantly from 8 o'clock last evening till one this morning to get over in an intelligible form four hundred words of the report per steamer Indian for the Associated Press, and at the latter hour so completely were the wires under the influence of the Aurora Borealis that it was found utterly impossible to communicate between the telegraph stations, and the line had to be closed.

But if the following newspaper transcript of a telegraph operator exchange between Portland and Boston is to be believed, some plucky telegraphers improvised, letting the storm do the work that their disrupted batteries couldn't:

Boston operator, (to Portland operator) - "Please cut off your battery entirely from the line for fifteen minutes."

Portland operator - "Will do so. It is now disconnected."

Boston - "Mine is disconnected, and we are working with the auroral current. How do you receive my writing?"

Portland - "Better than with our batteries on. Current comes and goes gradually."

Boston - "My current is very strong at times, and we can work better without the batteries, as the Aurora seems to neutralize and augment our batteries alternately, making current too strong at times for our relay magnets.

Suppose we work without batteries while we are affected by this trouble."

Portland - "Very well. Shall I go ahead with business?"

Boston - "Yes. Go ahead."

Telegraphers around the US reported similar experiences. "The wire was then worked for about two hours without the usual batteries on the auroral current, working better than with the batteries connected," said the Washington Daily National Intelligencer. "Who now will dispute the theory that the Aurora Borealis is caused by electricity?" asked the Washington Evening Star.

Working with solar-powered telegraph lines sometimes proved to be risky, however. As the sky filled with light, East Coast telegrapher Frederic Royce struggled to get his messages to Richmond, Virginia, his hand resting on the iron plate of his gear. Distracted by the displays, he also leaned on the system's "sounder," which indicated by audio whether the circuit was connected or not. At the same time, his forehead touched its ground wire.

"Immediately, I received a very severe electric shock, which stunned me for an instant," Royce wrote to The New York Times. "An old man who was sitting facing me, and but a few feet distant, said that he saw a spark of fire jump from my forehead."

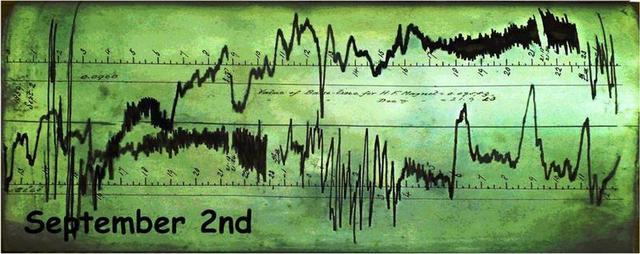

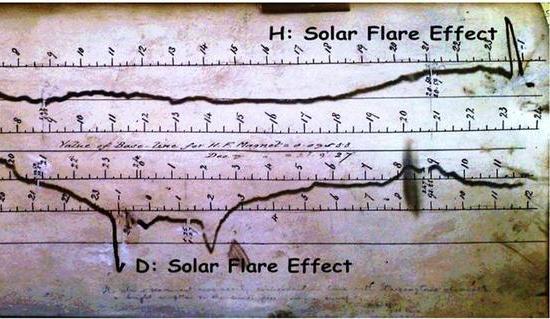

The night of Carrington's discovery, the electrical hurricane that had swept the globe peaked. The Great Auroral Storm had actually begun several days earlier with a similar incident on August 28, but it was Carrington and another astronomer, Richard Hodgson, who identified one of the solar flares that enveloped the earth in a week-long magnetic maelstrom. Because of their work, the episode was dubbed the "Carrington Event," and it consumed the world's attention for the week.

A livid red flame

In New York City, San Francisco, Boston, and Chicago, thousands of sky gazers wandered about the midnight streets, astounded at what they could see. "Crowds of people gathered at the street corners, admiring and commenting upon the singular spectacle," observed the New Orleans Daily Picayune. When the September 1 aurora "was at its greatest brilliancy, the northern heavens were perfectly illuminated," wrote a reporter for The New York Times. He continued:

At that time almost the whole southern heavens were in a livid red flame, brightest still in the southeast and southwest. Streamers of yellow and orange shot up and met and crossed each other, like the bayonets upon a stack of guns, in the open space between the constellations Aries, Taurus and the Head of Medusa—about 15 degrees south of the zenith. In this manner—alternating great pillars, rolling cumuli shooting streamers, curdled and wisped and fleecy waves—rapidly changing its hue from red to orange, orange to yellow, and yellow to white, and back in the same order to brilliant red, the magnificent auroral glory continued its grand and inexplicable movements until the light of morning overpowered to radiance and it was lost in the beams of the rising sun.

Popular descriptions of the spectacle appeared everywhere. In 2006, a team of space scientists assembled a collection of eyewitness newspaper accounts of the storm. What stands out in these reports is the astonishment, awe, and even pleasure that the world experienced for a week—followed by a sobering realization of how close our planet is to its indispensable star.

In Cincinnati, the aurora came "like that preceding the rising moon, while in the west a delicate crimson seemed to be thrown upwards, as if from the sun, long since gone down," wrote a journalist for the Cincinnati Daily Commercial.

Later, these strange fires overran the entire heavens—now separating into streamers, gathered at the zenith, and forming a glorious canopy—then spreading evenly like a vapor, shedding on all things a soft radiance; again, across the sky waves of light would flit, like the almost undistinguishable ripple produced by the faintest breeze upon the quiet surface of an inland lake; a pale green would now cover half the firmament from the east, while rich crimson met it from the west—then the ruddy light would concentrate itself at the zenith, while beneath it fell in folds of beauty the mild purple and green. To the east and to the west lay huge fields of luminous clouds, tinted with a bright rosy flush, wholly unlike that produced by the rising sun and if possible even more beautiful.

And so it went around the United States and the world. The sky appeared "blood red," noted the New York Herald. The storm produced "a beautiful halo, and at another period it had the effect of falling from the apex in showers of nebulous matter like star-dust," reported the The Hobart Town Mercury from Tasmania.

Not all reporters welcomed these images with pleasure. "Half-past eleven. The appearance now is positively awful," wrote a horrified correspondent for the San Francisco Chronicle on September 5. "The red glare is over houses, streets, and fields, and the most dreadful of conflagrations could not cast a deeper hue abroad."

Others took a pragmatic approach to the moment.

"Singular as it may appear, a gentleman actually killed three birds with a gun yesterday morning about one o'clock [in the morning]," disclosed the New Orleans Times Picayune, "a circumstance which perhaps never had its like before. The birds were killed while the beautiful aurora borealis was at its height, and being a very early species—larks—were, no doubt, deceived by the bright appearance of everything, and came forth innocently, supposing it was day."

reader comments

117