THE VILLAGE OF AHMED AWA—a single street of ramshackle shops and restaurants—sits inside a mountain gorge just above the fertile plains of Iraqi Kurdistan, about ten miles west of the Iranian border. Beyond the village, a dirt parking lot marks the start of the trail to the Ahmed Awa waterfall, one of Iraq’s most popular nature spots. The morning that I visited, in January, was clear and warm, but it was still unmistakably winter. The wild pomegranate, walnut, and fig trees that cover the slopes along the river leading to the cataract were bare, and I could see the torrent rushing by through a skein of skeletal branches. A cold rain had fallen during the night, and as I set off on my hike, joined by a Kurdish interpreter and the driver of our taxi, I had to keep to the edge of the trail, close to the drop-off, to avoid sinking into pools of mud.

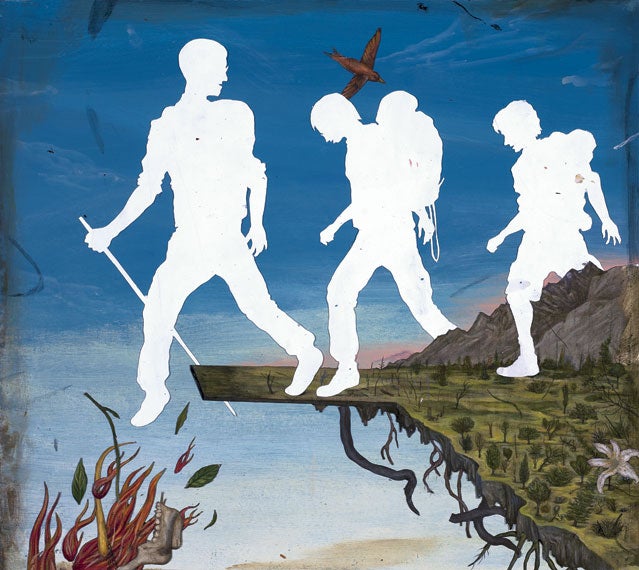

The Iran-Iraq border

The Iran-Iraq border

The Iran-Iraq borderShane Bauer

Shane Bauer

Shane BauerSarah Shourd

Sarah Shourd

Sarah ShourdJosh Fattal

Josh Fattal

Josh FattalShon Meckfessel

Shon Meckfessel

Shon MeckfesselAs we hiked into the Zagros Mountains, which rise to nearly 12,000 feet along the border between Iraq and Iran, the driver grew nervous. “We’re going to have lunch in Tehran,” he said with a tense laugh. He had reason for his gallows humor: Six months earlier, three Americans—Shane Bauer, 27; his girlfriend, Sarah Shourd, 31; and Josh Fattal, 27, Bauer’s former housemate from the University of California at Berkeley—had walked along this same trail, with disastrous results. The hikers had—accidentally, it seems—strayed across the unmarked border into Iran, been seized by border guards, accused of being U.S. spies, and transported to the notorious Evin Prison, in Tehran, where they remained as this story went to press, in March. Bauer, Shourd, and Fattal are experienced globetrotters who’ve traveled to such hot spots as Yemen, Kosovo, and Lebanon; two of the three speak Arabic. Yet somehow—through lack of preparation, cultural misunderstanding, ignorance, or a combination of all three—these sophisticated nomads had wandered into one of the worst places on earth to be an American. Now I was retracing their footsteps, trying to understand how they’d made such a catastrophic error.

The path was deserted; when the American hikers were here, at the height of summer, it would have been crowded with families of Iraqi Kurds. The trees along the river would have been leafy and bountiful with fruit, and wildflowers would have speckled the now monochromatic pale green slopes. Ahead of us, a sign in Kurdish script identified the settlement of Zorm, a cluster of stone-and-mud huts perched on an outcropping. We slid down a muddy slope to talk to a farmer drying pomegranate rinds on the roof of his house. He remembered seeing the Americans when they stopped for tea before continuing to the waterfall. Two mornings later, he said, police and intelligence officers swarmed the village, informing locals that “the Americans have been arrested in Iran.” The farmer suspected that their transgression had been deliberate, though there are no signs to announce the border. “Nobody has ever made that mistake before,” he said. “Who knows? Maybe it was their secret task to go.”

The trail became steeper, and the gorge narrowed. The sun was shining in a cloudless sky, burning off the mist that had shrouded the jagged, snow-dappled peaks ahead of us, in Iran. Fifteen minutes later, we reached a thundering 60-foot cascade that turned the turbines in an adjacent hydroelectric power station. There we met another local, a former peshmerga—a Kurdish freedom fighter—who’d battled the Iraqi army in these mountains in the eighties and now owned walnut orchards here. Over the water’s roar, he told us that the border was a two-hour walk east into the mountains. Almost all hikers come to look at the waterfall and then turn back, he said. But somehow the Americans had kept walking. From what he’d learned, they’d slept outside and crossed the border in the early morning, when the trail was empty.

“Nobody could warn them,” he said.

THE THREE HIKERS could hardly have picked a worse time to fall into Iranian hands. Hostility between the United States and the Islamist regime has reached a level not seen since the 1979 hostage crisis, when a gang of students and militants seized 66 Americans at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and held the majority of them for 444 days. Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Holocaust denials and anti-Israel diatribes, the surging power of Iran’s anti-Western Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and the regime’s suppression of the country’s pro-democracy movement have driven rhetoric to new heights of acrimony.

Several U.S. citizens have been seized or allegedly seized by Iran’s government in the past three years. These include Roxana Saberi, a former Miss North Dakota and Iranian-American journalist for National Public Radio, who was jailed for four months in 2009 on spying charges; Robert Levinson, a former FBI agent and private detective who disappeared in March 2007 while apparently investigating a cigarette-smuggling case for an unnamed client in the Persian Gulf; and Ali Shakeri, an Iranian-born mortgage banker and peace activist from California, who spent 140 days in Evin after he was arrested in 2007 while visiting his ailing mother in Tehran. According to Alireza Nader, an Iran specialist for the RAND Corporation, a California-based think tank, these arrests have become standard procedure, a situation that’s not likely to change. “It has been [the government’s] modus operandi since the 1979 revolution,” Nader says.

When a civilian is jailed in Iran, the U.S. government is dealt a hopeless hand. The State Department has had no diplomatic relations with Iran since 1979 and must rely on the Swiss Embassy’s Foreign Interests Section to help negotiate any release. In typical fashion, State’s diplomats have been extremely cautious about what they will say regarding the three jailed hikers. Philip Frayne, the U.S. Embassy spokesman in Baghdad, will only confirm that they have been reaching out to regional allies like Syria and Turkey. “We’ve asked everyone who has relations with the Iranians to put in a request with the Iranian government to release the three,” he says. One top official in the Kurdish regional government, former freedom fighter Sadi Ahmed Pire, maintains that Iraqi president Jalal Talabani, whose warm relations with Iran date back to the eighties, has appealed personally to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to free the Americans on humanitarian grounds. “The president [is making the case] that it’s a matter of fairness to make their stay in prison very short,” he says.

That’s certainly what their families hope. The hikers’ parents—Shane’s mother, Cindy Hickey, and her husband, Jim, in Pine City, Minnesota; Shane’s dad, Al Bauer, two hours south in Prior Lake; Nora Shourd, in Los Angeles; and Laura and Jacob Fattal, in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania—have reached out to the regime, sending letters to Ahmadinejad and appealing via video to Ayatollah Khamenei. They’ve also called on public figures in the U.S. and abroad to lend their voices to the free-the-hikers campaign.

The silence was finally broken on March 9, when Iranian authorities permitted each of the hikers to call home. Reliable reports had indicated that Bauer, Shourd, and Fattal had been treated with particular severity inside Evin: locked in solitary confinement, subjected to frequent interrogations, and, with the exception of a few letters from home and two visits from Swiss diplomats, denied contact with the outside world. But in the short phone calls—which lasted only several minutes each and were likely monitored by Iranian guards—the Americans said their treatment had been humane. Bauer and Fattal share a cell, they told their parents, and Shourd is permitted daily one-hour visits with her friends. The three said they were getting exercise, eating reasonably well, and even being permitted glances at state-run Iranian TV. But they were still in prison.

For all the hikers have endured, the stateside response has been muted compared with the attention lavished last year on Roxana Saberi, or on Current TV journalists Laura Ling and Euna Lee—who strayed across North Korea’s border from China in March 2009 and were sentenced to 12 years’ hard labor before being granted amnesty two months later. Few people buy the Iranians’ claim that the hikers were working for the CIA. But they lack powerful media sponsors, and they suffer from a widespread perception that their predicament is their own fault.

“‘Hiking’ between two countries which are in the news every day, and then calling it ‘outrageous’ when they are arrested is…completely ridiculous,” commented one reader on the Web site of the progressive magazine Mother Jones, to which Bauer has contributed occasional freelance stories. “These morons…deserved to be detained.” Many people I talked to about the case expressed bewilderment, even a hint of scorn, at how they could have been so clueless.

For the hikers’ families, the calls seemed a hopeful sign that their children might be released within weeks. But, whenever their ordeal ends, it serves as a frightening reminder of the political fault lines that often run along the world’s geographical boundaries. The trio’s imprisonment has drawn new attention to the dangers of adventure travel in an era when conflict zones can turn overnight into trendy destinations, guidebook writers can’t keep up with expanding appetites for edge-of-the-world experiences, and gung-ho vagabonds venture into places where having a U.S. passport can put you at risk.

As I discovered in my own travels through the region, Bauer, Shourd, and Fattal are indeed partly to blame; they went into Kurdistan with a shocking lack of preparation. Even so, they were not well served by those they turned to for advice, and they fell victim to a sequence of small mistakes and misunderstandings that snowballed into a catastrophe—and turned them from innocent backpackers into pawns in a high-stakes face-off between implacable enemies.

MOST OF WHAT the country has heard about the Americans’ capture has come from the so-called fourth hiker, Shon Meckfessel. A 37-year-old writer, musician, and student of Serbo-Croatian and Arabic now getting his Ph.D. in language theory at the University of Washington, Meckfessel traveled with Bauer, Shourd, and Fattal as far as the regional hub of Sulaymaniyah, a bustling town about 30 miles west of the Zagros Mountains. The night before their camping trip, he came down with a fever and stayed back at the hotel. He last saw his friends on Thursday evening, July 30, as they piled into a taxi for the 90-minute drive up to Ahmed Awa.

Meckfessel and his friends represent an idealistic breed of young American: cosmopolitan, curious, and engaged with the world. Each is the kind of expat—journalist, teacher, activist—who is devoted to bridging the gap between the U.S. and less developed countries, even in unstable areas where anti-American feeling may be rife. These travelers are in many ways the opposite of the ugly American—learning the local language, engaging with people, and debating their country’s policies in the bistros of Eastern Europe or the refugee camps of the Middle East. As Meckfessel says, “I’m interested in cultures that people in the U.S. misunderstand.”

The four converged in the Middle East through activist circles in the San Francisco Bay Area. Bauer, who grew up north of Minneapolis, and Fattal, who’s from the Philadelphia suburbs, met at Berkeley. After graduation, in 2004, Fattal became a staffer at Aprovecho, a nonprofit outside Eugene, Oregon, that designs low-impact stoves for the developing world. Bauer stayed in the Bay Area, trying to get a career as a journalist off the ground. He traveled in the Balkans and the Middle East and protested against the Iraq war.

Around 2005, Bauer met Sarah Shourd, a Berkeley grad from Los Angeles who was teaching English to newly arrived immigrants. The couple soon began living together in Oakland. They also found they had a mutual friend: Shon Meckfessel, another Bay Area resident whom Shourd had met on a relief trip to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and who knew Bauer from local music clubs and the activist scene.

In August 2008, the couple moved to Damascus, Syria, for a year. The capital of a Baathist police state, Damascus is nonetheless a seductive city with a secular atmosphere. Shourd studied Arabic and taught English at a language academy and to Iraqi refugees. Bauer freelanced for Mother Jones and The Nation. They fell easily into the thriving expat scene that revolves around the bars and cafés of the Old City.

Overall, they struck other Damascus expats as friendly and well-intentioned: Bauer is slight and energetic, while Shourd exudes a sweet, homey vibe that can belie her countercultural ideas. “They were very idealistic—a nice couple of kids,” says British freelance correspondent Kate Clark. “They wanted to make the world a better place.”

Last summer, Fattal and Meckfessel caught up with Bauer and Shourd. Fattal had just finished a semester as a teaching fellow at the International Honors Program, traveling around the world with 33 undergraduates. Meckfessel was spending the summer in Damascus after studying Arabic throughout the region. The four began planning a ten-day trip to coincide with Shourd’s summer break. They’d already seen Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan and were looking for a new adventure; after talking to a number of other expatriates, they settled on Iraqi Kurdistan.

“Friends told us they’d been to Sulaymaniyah, to the mountains,” Meckfessel says. “One said it was the most beautiful nature he’d ever seen in his life.” Known by travel-savvy Westerners as the “safe Iraq,” Kurdistan has been pro-American since George H. W. Bush sided with the Kurds in their uprising against Saddam Hussein after the Gulf war of 1991. There hasn’t been a significant terrorist attack there since 2004.

But getting precise travel information proved difficult. The Americans had loaned their Middle East Lonely Planet guide to a friend and resorted to a poorly detailed map printed from the Web. “We didn’t feel we had to do real in-depth preparation,” Meckfessel admits.

FOR DECADES, the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan was one of the most violent corners of the Middle East. The center of an ethnic Kurdish belt that extends from eastern Turkey to western Iran, it was targeted in the eighties by Saddam Hussein, who—in an effort to stamp out a series of rebellions—razed 4,000 Kurdish villages, slaughtering at least 50,000 civilians. In April 1991, Saddam’s forces drove hundreds of thousands of Kurds across the mountains into Turkey. The first President Bush demanded the withdrawal of Iraq’s troops, which helped the Kurds run an autonomous government. After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003, the Kurds began to develop their economy and open up to foreign tourists.

Many of these are European, but over the past two years a steady trickle of Americans—low-budget travelers who work in the region and retirees on package tours—have made their way here, drawn by the snowy mountains and green valleys, the culture, or simply the thrill of visiting Iraq. The standard route is overland across the Turkish border, or by Atlasjet flights from Istanbul to the Kurdish capital of Erbil. Still, Rebwar Daoud, who runs Babel Tours, in Erbil, told me that drumming up business isn’t easy. “We are trying to create a good image of Kurdistan,” he said, “but many people of Europe and America think, ‘You are going to Iraq? Oh, no, you are crazy.’ “

To get a sense of the hikers’ overland journey, I flew to Diyarbakir, in the Kurdish region of Turkey. I spent a night in a 16th-century converted caravansary, then hired a taxi to take me 175 miles east to the border at Silopi, where the four had crossed into Iraq. Darkness fell and, as the lights of the Iraqi border town of Zakho shone on the horizon, we rumbled across a suspension bridge over the Khabur River. At the border post—flying only a Kurdish flag, not an Iraqi one—a smiling official served me tea and stamped my U.S. passport after a cursory scan. There, I met my translator—an Iranian Kurd named Jamshid—and hired a driver before heading on in the morning to Sulaymaniyah, six hours southeast.

The road twisted and turned through treeless mountains and fertile plains, past villages rebuilt after being bulldozed by Saddam. We reached Sulaymaniyah around nightfall and retraced the hikers’ path to the Miwan Hotel, a second-floor hole-in-the-wall a few doors down from a pirated-DVD shop.

“They were polite, no trouble; they didn’t even ask to take a shower,” said Muzafad Mohammed Zeli, the proprietor, a mustachioed 55-year-old wearing traditional baggy cotton pants. On the wall of the reception area, I noticed three photos of the Ahmed Awa waterfall. These pictures, Meckfessel recalls, were part of what had piqued the hikers’ interest in the first place. “All of us asked the owner where we should go to see the mountains,” he says, “and he pointed at the photos.”

Zeli, Meckfessel says, was one of ten people in Kurdistan who recommended they visit Ahmed Awa, but none of them mentioned that it was anywhere near the border. Zeli, however, insisted that he’d never discussed Ahmed Awa with the four. “If I had known,” he told me, “I would have warned them not to go.”

Ahmed Awa wasn’t on the Americans’ map, but they decided that it must lie in a mountain range near Dukhan, north of Sulaymaniyah and about 30 miles west of the border. They imagined following a hiking circuit through the mountains, camping under the stars. “For the Kurds, Ahmed Awa is a two-hour trip,” Meckfessel says. “We were thinking in terms of Yosemite—several days.”

The friends settled into a brightly painted room with four beds, for which they paid 40,000 Iraqi dinars (about $35). The next day they toured the city, stocked up on provisions for their trip, and e-mailed home. “Hey sweetness,” Shourd wrote her mother. “So, we’re traveling. Actually, we’re in N. Iraq! It’s totally safe. The Kurds in this area have been pro-American since 1991. …So, don’t worry. Tonight we’re going camping. I love you.”

On the walk back to the hotel, Meckfessel began to feel feverish. He stayed behind as the other three set off in a taxi for the mountains at about 6:30 P.M. The plan was to meet on the trail the next day. Early in the morning, Friday, July 31, he got a cell-phone call from Bauer, who urged him to hurry and join them. “You totally could have slept here,” Bauer told him. “The weather was warm all night. It was really comfortable.” The hikers had camped under blankets in a clearing beyond the waterfall, Bauer said, then gotten up at 4 A.M. and started hiking again in the dawn light.

Astonishingly, Bauer and the others still didn’t realize they were anywhere near Iran; armed only with their Web map, they continued east, oblivious to their true location. Later, local newspapers would report that the three Americans were indeed warned—by a soldier at the last checkpoint before Ahmed Awa. “Be careful,” he allegedly told them. “There are no signs about the Iranian border.” If he did tell them, the message didn’t sink in. But six months later, when I passed through the same checkpoint, two guards inspected my passport carefully and demanded that Jamshid, my interpreter, leave his own identification card behind.

“If you are arrested in Iran,” one of them affably explained, “we can find the clues more easily.”

Even if the hikers had known the border was nearby, they still could have missed it. According to retired U.S. colonel Harry Schute, who runs tourism and security businesses in Erbil, “you would think that it would be a readily identifiable feature like the top of hill or a river, but it’s just the middle of a slope, with some blocks on the ground. And if you don’t know what that rock means, you can cross without realizing it.” There’s a huge smuggling industry on the border, Schute says, and the hikers—who speak no Farsi or Kurdish—could’ve been reassured by the movement back and forth. “There’s a lot of traffic. Watching these folks, you might think you’re OK, and next thing you know…”

Shortly after noon that Friday, Meckfessel sent Bauer two text messages saying he was on his way. Both went unanswered. “Then, at 1:13 P.M., I saw Shane was calling,” Meckfessel recalls. “I said, ‘How are you doing?’ and he said, ‘We’re in trouble.’ He was really serious. Worried, but not panicked.”

Bauer was inside a vehicle. “We were hiking and suddenly we had Iranian guards around us,” Meckfessel remembers him saying. “We had hiked up to the border and we didn’t realize it. We’ve been taken into custody, and they’re taking us somewhere.”

“When he said ‘Iran,’ ” Meckfessel tells me, “it was like saying he’d just landed in Vanuatu. It was the most shocking thing I’d ever heard.”

CINDY HICKEY was working at her Pine City, Minnesota, animal-training-and-nutrition business on a sweltering July morning when she received an overseas call. Through a crackling connection, a consular officer from the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad informed her that her son, Shane, had apparently been arrested by “authorities” inside Iran. At that point, the embassy’s only information came from Meckfessel, who, after reaching a duty officer at the embassy by cell phone from Sulaymaniyah, had been flown to Baghdad and debriefed. Twenty minutes later, Hickey got a second call from the State Department, joined by the FBI. “They had no more details,” she says. “They said, ‘As soon as we find out anything, we’ll call you.’ “

Several days passed before both Iran and the U.S. confirmed the hikers were in custody. For their families, this set off an all-consuming campaign of vigils, letters to Ahmadinejad and other Iranians, and meetings with U.S. public officials, including senators Al Franken and Arlen Specter and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

At first daily, and now “regularly,” Hickey says, the families check in with a State Department contact who keeps them apprised—up to a point—about the government’s efforts. “I feel like they are doing the best job they can, considering the relations between the U.S. and Iran,” she told me in early February. “There are a lot of things they can’t tell us.”

Through the State Department, they received sketchy accounts of visits made by two Swiss diplomats to Evin Prison on September 29 and October 29. Each hiker, Hickey says, “passed a private message to the Swiss, four or five sentences. Shane said, ‘I love you, I miss you,’ he talked about his sisters, and said he was able to get some of our letters. He said, ‘I’m physically OK, I’m strong, but lonely.’ “

In addition to the State meetings, the families began conferring on their own. “We brainstorm, we put things on the table, we weigh and balance things,” Hickey says. In the early days, they wrestled with the question of how they should handle the media—whether to keep a low profile and let State work its back channels or to make as much noise as possible. Hickey initially contacted Outside about her son’s plight. But last December, when I reached out to the families, she responded with a brief e-mail thanking me for my interest but letting me know that they weren’t granting any interviews. Weeks later, they changed their minds and have since made themselves available to the press.

They’ve also worked to keep their children from being forgotten: Laura and Jacob Fattal have organized vigils in their Cheltenham, Pennsylvania, hometown, as well as a public appeal on the families’ Web site, FreeTheHikers.org. In December, Nora Shourd donned a chador, the floor-length garment worn by women in Iran, and released a video addressed to Ayatollah Khamenei. “Your Excellency,” she said. “They are good people. They did not mean to enter Iran. They meant no harm to the Islamic Republic…and have a deep respect for your ancient and noble civilization. If they entered Iran, it was an innocent mistake.”

For a long time, their appeals were met with silence. Iran refused the Swiss Embassy’s requests for further prison visits, and information dried up. Iranian lawyer Masoud Shafie—whom the family hired last fall, anticipating espionage charges—has continued to demand that the judiciary allow him to meet his clients. Reached by phone in Tehran in January, the attorney told me he’d gotten nowhere. “They don’t allow me to see them, and it is not according to the rule,” he said. “I told the judge that they must charge them after four months. Already six months have passed. They say, ‘Wait, wait, wait.’ “

In February, the door cracked: Iran’s top human-rights official, Mohammad Javad Larijani, told journalists in Geneva that he’d recommended to Iran’s judiciary and security forces that the mothers be allowed to visit their children. They immediately sent a letter to Ahmadinejad urging him to grant them visas. And then came the day in March.

“We got no warning, and neither did they,” Nora Shourd says. That morning, she noticed an unknown caller ID on her cell phone and let the call go to voice mail. When she played back the message, she was astonished to hear her daughter’s voice: “Hi, Mom,” Sarah said, “it’s me. They’re giving me the chance to call from prison. I’m ok and I’m coping.” Shourd was overwhelmed with emotion—and regret that she’d missed the call. But Sarah phoned back 20 minutes later, and the mother and daughter spoke for three rushed minutes. Sarah quickly sketched in prison life—she was reading the GRE preparation guide Nora had sent (before her capture, she’d planned to return to the States to study women’s issues) and was able to see Bauer and Fattal. “The big fear,” Nora says, “was whether or not they were OK, and that big fear was lifted. It feels like things are moving a little. It could be that they just threw us a crumb, but the kids are hopeful.”

According to Alireza Nader of the RAND Corporation, the calls are indeed a positive sign, but they don’t necessarily presage the hikers’ release. The regime, he says, “ramps up repression when it feels threatened, but it’s been feeling less threatened lately, so they could be more relaxed.” Despite this goodwill gesture, Nader says, a real breakthrough may still require backroom negotiations.

“These innocent people have become bargaining chips,” agrees Abbas Milani, director of Iranian studies at Stanford University, who spent a month in solitary confinement at Evin during the reign of the last shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Iran wants the U.S. to ease pressure for reform and to lift economic sanctions, Milani believes; more specifically, it is seeking the release of 11 Iranian nationals, reportedly including intelligence officers and Revolutionary Guards, held by the U.S. military in Baghdad jails.

There may be a precedent for such a swap. Two months after Roxana Saberi’s release in May 2009, the U.S. military freed five Iranian prisoners in Baghdad. Embassy spokesman Philip Frayne insists that “there was no deal on Saberi, despite how it may look.” Regardless, in early February, Ahmadinejad publicly raised the possibility of a prisoner exchange in an interview with Iranian state television. Secretary of State Clinton immediately rejected the idea and again called for Iran to release the three “on humanitarian grounds.”

While some experts had cautioned that, given the depth of animosity between the U.S. and Iran, the Americans could be in for a longer stay, Milani can envision an eventual pardon by Ahmadinejad. Or the case might follow the Saberi model: She was sentenced to eight years for espionage, but an appeals court knocked the charge down to possession of classified information and gave her a two-year suspended sentence.

“I think Iran has realized there isn’t much wiggle room there,” he says, “and gradually they will step down. I would not be surprised if, a year from now, these young people are writing their memoirs at home.”

IT IS A ROUGH eight-hour drive east from the border near Ahmed Awa to Evin Prison, built at the foot of the Elburz Mountains in northern Tehran. A pale-blue metal gate in the dull-red brick facade leads to cell blocks, solitary-confinement and interrogation wards, a courtroom, and an execution yard—where 29 convicted murderers, rapists, armed robbers, and drug traffickers were hanged on a single day in July 2008. In recent years, the prison has also become the destination for opponents of the Islamist regime.

In March, the hikers described a tolerable existence inside Evin. But the calls were short, and Nora Shourd says that she could hear what sounded like an Iranian male voice speaking English in the background, indicating that they were being closely monitored.

From accounts of others who’ve spent time inside Evin, including Roxana Saberi, a picture has emerged of what the Americans may have gone through. Prison officials likely separated them upon arrival. The three would have received uniforms—beige synthetic sweats for all three, and, for Shourd, a chador. Then they would have been placed in single-person interrogation rooms, isolated from the other prisoners—about 2,600 men and 400 women in 2006, the last time the international press had access.

Saberi, who spent 18 days in solitary last winter, says that, as high-value prisoners, the Americans were likely settled either in Ward 209—run by the Intelligence Ministry—or Ward 240, administered by the Revolutionary Guards. Each ward consists of several corridors painted antiseptic white, each lined with four or five cells, with a thin carpet and a tiny window covered by a wire-mesh screen that lets in a trickle of daylight. In the first weeks of their captivity, they may have been kept blindfolded and interrogated for hours a day, an experience that Saberi describes as disorienting and often terrifying.

“You don’t know how many people are in the room with you,” says Saberi, who chronicled her experiences in Between Two Worlds: My Life and Captivity in Iran, which was published in March. “They claim you are guilty [of spying], and you believe they believe it. They threaten you with a long time in prison unless you confess.”

Saberi’s quarters were a spare cell; she slept on the floor beneath a blanket, with a bare bulb kept on 24 hours a day and a small heater that never seemed to generate enough warmth. Her only contact came when the guards delivered meals: white bread and a cheese slice for breakfast, rice and stew for lunch, canned food for dinner. “Time passes so slowly, especially when you’re in solitary,” she says. “They are wondering every day, when will they get out of there?”

Halfway across the world, the hikers’ friends and families wait with them. In Washington State, Shon Meckfessel can’t keep his mind on his studies; he admits he’s dealing with a form of survivor’s guilt. “I’ve struggled,” he says. “I know my friends wouldn’t want my life to fall apart, and when they get out I don’t want them to see everything in shambles. Sometimes I think they’re going to get out soon, then I read something and I think they’ll be there forever. It’s horrible, unimaginable stress.”

Meanwhile, in Minnesota, Cindy Hickey was relieved to find out that her son was not languishing in solitary and clings to the belief that the Iranians’ attitudes are softening. “I know my son,” she says. “I know how responsible he is, and I can’t believe he’d put anyone in harm’s way. We are both hikers,” she says. “It’s beautiful, there’s a trail, and you want to know what’s around the next corner.”