The Port of Los Angeles, 23 October 2011. At the Goofy Pool on deck 9 of the Disney Wonder, the Adventures Away celebration party has begun. “Goodbye, stress!” the cruise director shouts. “Hello, vacation!” The ship’s horn sounds out When You Wish Upon a Star, to indicate that we’re about to set sail, to Mexico. It’s a nice touch. The ship has just won the 2010 Condé Nast Traveller crew and service award.

I’m standing on deck 10, looking down at the dancing crowds of guests and crew. There are 2,455 passengers this week, and 1,000 employees. You can spot the Youth Activities team in their yellow tops and blue trousers. They look after the children in the Oceaneers’ Club on deck 5.

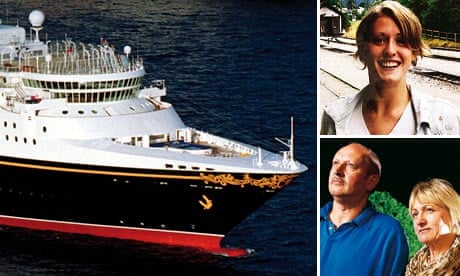

There’s no talk of it, but many people on board know something terrible occurred on this route – to Puerto Vallarta and Cabo San Lucas – earlier this year. At 5.45am on Tuesday 22 March, a CCTV camera captured a young woman on the phone in the crew quarters. Her name was Rebecca Coriam. She was 24, from Chester, and had recently graduated from a sports science degree at Exeter University. She’d been working in Youth Activities on board for nine months, and apparently loved it. But on the phone she was looking upset.

“You see this young boy walk up to her to ask her if she’s all right,” her father Mike told me a few weeks ago, sitting in the family’s back garden in Chester. “She said, ‘Yeah, fine.’ Then she put the phone down. She turned around. She had her hands in her back pockets, which she always did. Then she put her hands to her head like this, pushing her hair back…” Mike did the movement. It looked normal. “And then she walked off.”

And that’s the last anyone has seen of her. She just vanished.

When she didn’t report for work at 9am, the crew Tannoyed her. They searched the ship and called the Mexican coastguard, who searched the waters, all to no avail. That was seven months ago.

“Now, whenever we call anyone, all they say is, ‘The investigation is ongoing,’” Mike says. “We’ve tried emailing, telling them how we feel, how it’s getting harder...” He pauses. “But nothing. Just, ‘It’s ongoing.’”

Mike and his wife Ann have created a website – Help Us To Find Rebecca (rebecca-coriam.com) – and have organised fundraising events. The day I visited, the house was filled with raffle prizes, chocolates, board games and soft toys, donated by well-wishers. Mike said on some days they were just functioning, but on others they didn’t know if they were coming or going.

They said only one police officer has ever been assigned to investigate Rebecca’s disappearance. He flew in from Nassau in the Bahamas, 1,500 miles from the ship – just one man charged with conducting a forensic investigation and interviewing 3,000 passengers and crew. He took charge because the ship is registered in the Bahamas, for tax reasons. It wasn’t deemed relevant that it’s based in Los Angeles, the company’s head office is in the UK, Rebecca was British, and she went missing in international waters between the US and Mexico. (For European passengers, this holds true for all cruise liners, but a law passed last year means if a US citizen disappears on a cruise ship, the FBI now has jurisdiction.)

Mike and Ann have met the Bahamas officer only once. They flew to Los Angeles on 25 March to meet the ship as it arrived back. The Disney people showed them the CCTV footage and introduced them to the policeman.

“I asked him, ‘Are you going back on the ship now?’” Mike said. “He said, ‘No, I’m going back to the Bahamas.’ I thought, ‘Hang on, you only got to the ship on Friday.’ He had just Saturday there and that was it. The passengers weren’t questioned.”

“Not at all?” I asked.

“No. Not many of the crew, either,” Ann said.

I told Mike and Ann that I would book myself on to the cruise, ask a few questions, just see what I could find out. They said they’d be pleased for whatever help they could get.

In the atrium on deck 3, passengers queue for Mickey Mouse’s autograph. I overhear an adult passenger ask a crew member, “Exactly how many Mickey Mouse symbols are there on board?” He looks taken aback. There are about 20 within our immediate vicinity – art deco mouse ears on the frosted glass doorways, swirly mouse ears on the carpet. “I don’t know,” he replies. The passenger looks annoyed that his question can’t be answered. “I can point out some hidden Mickeys,” the crew member adds, conciliatorily. It’s a Disney tradition to embed tiny mouse symbols into the architecture. Fans love to spot them.

I wander into one of the bars and get talking to a waiter. “What’s it like working here?” I ask.

“It’s all about the show,” he replies. “When you’re out among the guests, you’re always on show. Even if you’re a waiter, or a cleaner, or a deck hand.”

“How long have you been on board?” I ask.

“Seven months. I’ll be going home in 40 days – 44 to be exact.” He laughs. “Seven months is long enough. Being away from your family is hard.”

“Were you on board when Rebecca Coriam vanished?” I ask.

He narrows his eyes. “I don’t know anything about it,” he says. There’s a long silence. “It didn’t happen,” he says. He looks at me. “You know that’s the answer I have to give.”

It’s a beautiful, clear night outside on deck 4. Ahead of us are the lights of another cruise ship. A few days later – when we reach Puerto Vallarta – I spot it again. It’s called the Carnival Spirit. Forty-three people have vanished from Carnival cruises since 2000. Theirs is the worst record of all cruise companies. There have been 171 disappearances in total, across all cruise lines, since 2000. Rebecca is Disney’s first. A few days ago, Rebecca’s father emailed me: “Would like to inform you the number of people missing this year has just gone up to 17. A guy has gone missing in the Gulf of Mexico. The Carnival Conquest.” By the time I get off this ship, the figure will have gone up to 19.

When someone vanishes from a cruise ship, one of the first things that happens to their family members is they receive a call from an Arizona man named Kendall Carver. “When you become a victim, you think you’re the only person in the world,” Carver told me on the phone. “Well, the Coriams found out they aren’t alone. Almost every two weeks someone goes overboard.”

Carver says the numbers have reached epidemic proportions and nobody realises it because it’s in the industry’s power to hush it up. He lost his own daughter, Merrian, back in August 2004, from the Celebrity Mercury. Even though the cabin steward reported her missing on day two, Carver said, no alarm was ever raised. “He reported her missing daily and they told him to forget it.”

So the chocolates piled up on her pillow. When the Mercury docked in Vancouver – as Carver later testified at a US Senate subcommittee hearing – nobody from the ship said anything, not to the police, the FBI, nobody. They just quietly placed Merrian’s belongings in storage, then gave them to charity. “If we hadn’t eventually traced her to that ship, she would have vanished,” he said.

At the time, Celebrity Cruise Line issued a statement saying, “Regrettably, there is very little a cruise line, a resort or a hotel can do to prevent someone from committing suicide.” But as Carver points out, the case is still open. Later, the company added, “There is probably nothing we or any company could do that would make the parents feel the company had acted sensitively enough.”

Now Carver leads a lobby group called International Cruise Victims. Over the phone, he told me theories of murder, negligence and cover-ups. Sometimes he sounded angry and xenophobic; at other times he was incredibly compelling.

“Think of where those cruise workers are from,” he said. “They’re low paid, from third-world countries, on those ships for nine months at a time. The sexual crime rate is 50% higher than in the average American city.”

It’s true that passengers on just one ship – the Carnival Valor – reported nine sexual assaults to the FBI in less than one year. “You’re on a ship,” Carver said. “There’s no police. Once you leave the port, you’re in international waters. Who do you think is attracted to working on those ships?”

“Do you think your daughter was murdered?”

“The answer’s yes,” he said. “That’s the story among the crew.” He paused. “Put murder to one side. Just think about the drinking. Royal Caribbean has just started a policy of unlimited drinks for one price. Celebrity is doing it.”

I don’t think drunkenness is an issue on the Disney Wonder. You’d have to drink a frozen piña colada the size of a glacier to get drunk, such are the measly measures they serve here.

“There’s a man in Ireland had a 15-year-old daughter,” Carver said. “One cruise served her eight drinks in an hour. She went to the balcony and threw up and went overboard. She was gone.”

The case he’s talking about is that of Lynsey O’Brien, who went missing on 5 January 2006 while on a cruise with her family off the Mexican coast. The cruise line, Costa Magica, conducted its own investigation into her disappearance and decided there was “no evidence of an accidental fall”, that Lynsey had shown the bartender ID stating that she was 23 years old and that her death was caused by “underage drinking”. While they “continued to extend their deepest sympathy” to the family, they claimed their report cleared them of any wrongdoing.

“In other corporations, police get involved,” Carver said. “On cruise ships they have, quote, security officers, but they work for the cruise lines. They aren’t going to do anything when the lines get sued. We came to the conclusion cover-up is the standard operating procedure.” He paused. “And the Coriam girl. Where is the CCTV footage?”

According to articles published at the time of Rebecca’s disappearance, in the Los Angeles Times and Cruise Law News, Disney claims to have no footage of Rebecca going overboard. They refuse to “disclose the number of CCTV cameras or their locations for security reasons”.

“If there’s a video that shows your daughter going overboard,” Carver said, “that’s the end of the story. There’s no way someone can go off a ship and it not be recorded.”

At 7am on the Tuesday, I stand on deck 4 as we pass the stretch of ocean where Rebecca went missing. A school of dolphins leap into the air, doing back-flips. Passengers around me gasp. A young crew member from Ireland passes and I ask her about life in the crew cabins. “It’s like being inside Harry Potter’s closet,” she replies.

She means it’s magical, but tiny and dark. Their cabins are windowless, below sea level, like steel boxes. Crew members are contracted to work seven days a week for four-, six- or eight-month stretches (according to how high up the ladder they are) before being allowed a few months off. At 10pm one night, I see some women from Rebecca’s department – Youth Activities – playing with kids on the stairs. It seems they’re on duty as long as there are kids who need entertaining. A former member of staff, Kim Button, has written a blog about life on the Wonder: “I don’t think it’s possible to imagine how tiny a crew room is without actually seeing it! Seriously, your mind can’t even fathom such things. We had staff meetings at 2am, the only time when one of us wasn’t working, so even if your work day ended at 10pm, you couldn’t get much sleep because you had to be in a meeting at 2am… The crew pool is literally one of the few places where crew members can just hang out and be themselves, without fear of acting improperly in front of guests.”

Even though life on board is, for a guest, assiduously magical, with total professionalism and constant Broadway-style high-budget shows, bingo, origami and acupuncture classes, films under the stars and shore excursions to snorkel with tropical fish and ride horses through Mexican rainforests, from time to time I detect tiny flashes of cabin fever. I watch a children’s entertainer try out a move in which he throws a stuffed pelican to his assistant. It accidentally hits her in the face. “You’re supposed to catch the pelican!” he snaps.

“My boss,” she mutters, looking embarrassed.

In a shore excursion, a Mexican crew member asks some passengers to stand in a straight line, two by two, while we wait for the bus. Every passenger feels the need to say something facetiously passive-aggressive in response.

“Oh, a straight line!” one says.

“Can it not be a little crooked?” says another.

And so on, practically all the way down the line. The crew member looks upset and embarrassed.

I’ve decided the only place Rebecca could have fallen from is the deck 4 jogging track. The railings everywhere else are just too high. She was a keep-fit fanatic. My theory is that after the 5.45am phone call, she went for a jog and slipped. So I’m surprised to spot four CCTV cameras on deck 4 – two on the port side, two on the starboard, evidently capturing every inch of the deck. They’re hard to see at first as they’re shaped like long tubes and look like some kind of nautical equipment.

A man in yellow overalls is varnishing a railing. I glance anxiously inside the atrium. There’s a big Cinderella party going on. Someone is singing a song about how we have to have “faith, trust and pixie dust”. There’s a crew party going on somewhere, too – I hear massive screeching and laughter from behind a steel door. It sounds very different from the guest parties, like a pressure cooker letting off steam.

I sidle up to the man doing the varnishing. “That girl who went missing back in March,” I say. “She must have fallen from this deck?”

He looks surprised: “No, she went from deck 5.”

“But there’s no outside space on deck 5,” I say.

“Go to deck 10, walk to the front of the ship and look down,” he says. “You’ll see the crew swimming pool. That’s where she went from. The starboard side.”

“How do you know this?” I ask him.

“I was on the ship that day. Everyone knows.”

“How?” I ask.

“They found her slipper,” he says.

I walk up to deck 10 and look down. And I see it. The crew swimming pool looks nice – bigger than some of the guest pools. But it’s the swimming pool equivalent of an inside cabin. There is no view of the ocean because behind the railings is a high steel wall. It reaches well above head height. There is no way someone could accidentally fall from there.

Back on deck 4, the man is still varnishing.

“I saw it,” I say.

“God bless her,” he says.

“It must be a very intense life, working on the Disney Wonder,” I say. “You’ve got those tiny, claustrophobic cabins. The passengers are very demanding. You work every day for six months. You have to be a Disney-type person the whole time, even when you’re varnishing railings…”

He looks at me as if I’m nuts. “We don’t spend any time in our cabins,” he says. “We just sleep and shower there. We spend our free time in the mess hall or by the crew pool.”

A group of his fellow deck workers join us. “Disney aren’t slave masters,” one says. “We get to go on shore. We get breaks. Everything you’ve got up here, we’ve got down there.” He points to the bowels of the ship. “We’ve got a library, a gym, a games room, a swimming pool. I don’t have a flatscreen TV or a gym at home. I have them here. The only thing I miss is my family.”

“But all that having to be on show for the guests all the time…” I say.

“All the big smiles and happiness,” someone replies, “it’s all real. You couldn’t act that.”

“Disney wouldn’t hire you if you weren’t that sort of person,” someone else says.

“But what about Rebecca Coriam?” I say. “Did you know her?”

A few of them nod. “She was a lovely girl,” one says. “Not emotional. Just like everyone here. Nice and friendly and happy.”

“Then why…?” I say.

“I don’t know,” he shrugs. “But there’s nothing dark or sinister going on. This is Disney.”

Over the next few days I ask more people, and every time I get the exact same response: she jumped from the front of deck 5, at the crew pool.

“Disney knows exactly what happened,” one crew member tells me. “That phone call she had? It was taped. Everything here is taped. There’s CCTV everywhere. Disney have the tape.”

“What’s in the tape?” I ask her.

“I don’t know, but I know someone who knew her well. Would you like me to introduce you?”

And so, after everyone has gone to bed, I have a brief conversation with one of Rebecca’s closer friends from the ship.

“Do you know what was in the tape?” I ask him.

He shakes his head. “Not exactly. I know she was having a fight with her partner.” He pauses. “What’s it ever about? It’s about love, relationships. There’s no mystery. She was just a lovely girl with underlying sadness.”

The next morning, as we sail back into the Port of Los Angeles, a crew member beckons me over. He says he’s heard I’ve been asking questions about Rebecca Coriam and he wants me to know that suicide is not the only possibility. Maybe, he says, after the phone call she took a walk to clear her head and the wind lifted her away.

“But the steel wall is so high down there,” I say.

“I was on the ship that day,” he says. “It was a rocky day. One time a friend of mine was called early in the morning. The deck by the crew pool was really windy and slippy, and someone was walking there, and my friend was called to get them inside. Disney took it really seriously. The guy got sent home.”

“So she could have fallen?” I ask.

“She could have fallen,” he says.

We pull into the port. This is where Mike and Ann came on 25 March after receiving a call from Disney executive Jim Orie to say Rebecca was missing. They were here in time to see the passengers disembark.

“We were hoping we could have spoken to some of them, but we never got the opportunity,” Mike told me back in Chester. Ann added: “They kept us in a car with the windows all blacked out.”

“Did you get the feeling they were deliberately keeping you away from the passengers?”

Mike: “Well…”

Ann: “Probably.”

“But Disney were being polite and helpful and sympathetic?” I asked.

“Oh yeah,” said Mike.

After the passengers had disembarked, Mike and Ann were taken on board. They were put in a room that quickly filled with Disney executives and the girl Rebecca had spoken to on the phone at 5.45am.

“Did you ask her what they’d talked about?” I asked. “Why Rebecca had been upset?”

They shook their heads. “We would have liked to have asked more, but by the time we’d flown over we were jet-lagged,” Ann said. “We hadn’t slept since the Tuesday. We flew out on the Friday. We hadn’t eaten…”

“With hindsight, it might have been better if we’d gone out a little later,” Mike said.

“When you were more able to ask questions?”

He nodded. “But your daughter’s missing, so you don’t think like that, do you? Also, we wanted to be quick to meet some of the passengers.”

Mike remembers thinking, as he sat in that room on the ship, that their uselessness at getting information wouldn’t be a problem because there would be plenty of other opportunities to ask questions. They had no idea they would never have another chance.

The next day, 1 November, Rebecca is discussed in the House of Commons. Her MP, Stephen Mosley, says Disney was “more interested in getting the ship back to sea than in the case of a missing crew member” and “it’s appalling” that only one policeman from the Bahamas – “an authority internationally recognised as almost toothless” – was called to investigate. He said “flag of convenience” countries such as the Bahamas – as they’re called in the shipping world – shouldn’t be left to conduct these kinds of investigations.

I call Disney. Their spokesperson tells me, “If you talked to crew members, you’ll know Rebecca’s disappearance has been difficult and heartbreaking for everyone.” And beyond that they can say nothing much else except, “The police in the Bahamas are also telling us the investigation is still ongoing. They have not shared a timeline with us, either.”

“Is it true the telephone call Rebecca made shortly before vanishing was taped?” I ask.

“That pertains to specific details about the investigation and so it’s not appropriate for us to share that kind of information,” she replies.

“Is there anything you can tell me?” I ask.

“I can tell you we wish we knew what happened as much as anyone,” she says.

The officer in the Bahamas, Paul Rolle, doesn’t return my calls.

I call Mike and Ann. I tell them about my week on the ship. When I get to the part about the waiter saying, “It didn’t happen”, Mike sighs and says, “Oh. Yeah.”

I tell them about all the CCTV cameras and Mike says, “They could have had them fitted since.” (It’s a measure of him that he’ll not descend to conspiracy theories about Disney.) I tell them about the high steel wall on deck 5, about how that sadly points to suicide, although not definitely. I ask if I’m telling them things they didn’t know.

“No, we’ve been through all this,” Mike says.

“Was there any underlying sadness?” I ask.

“No, no, no,” Mike says. “There isn’t.”

“A crew member told me Disney have a tape of the telephone conversation,” I say.

There’s a silence. “Did they say...” Mike pauses. “Was there any idea…?

“No,” I say. “No idea.”

I say I regret never talking to one of her really good friends on board. And then – later that night – a woman telephones. I’ll call her Melissa. She says she’d never have talked to me had Mike and Ann not asked her to.

“When did you last see Rebecca?” I ask her.

“It was at 11pm, the night before she went missing. We’d both just finished work, and she was trying to pull my false eyelashes off.” She laughs. “She had her head on my knee and we were chatting and messing about.”

“Where was this?” I ask.

“In the secret corridor,” she says. “There’s a whole different world underneath the ship deck. We have parties down there, private showings of films. It’s absolutely brilliant. Bex said, ‘Are you going to the bar?’ I said, ‘Yeah’ but I didn’t for some reason. And that was the last time I saw her.” She pauses. “She was the most amazing little burst of energy. You were completely drawn to her. She loved life. Bouncing around all the time. She was one of my best friends, but it could get a bit much.” She laughs again. “You come in from a heavy night and she’d be zapping around everywhere. Playing tricks on you. She’s very mischievous.”

“Someone told me she’d had a fight with her partner,” I say.

“That ship absolutely seethes with rumours,” Melissa says. “Yes. She was in a relationship, and there were problems, and it was upsetting her. It was a very, very intense relationship. It was great and then it was awful. They were both fiery, passionate personalities.”

“Do you think that’s what the call was about?”

“I can’t think of any other reason why she’d have been upset and wandering around by herself at 6am,” Melissa says. “From what I’ve heard, she was on the phone to a mutual friend. Not the girl she’d been having the relationship with.”

And then Melissa starts telling me some odd little things. She says after Rebecca went missing, Disney had a little ceremony. They put flowers at the wall next to the crew pool, “where they think she might have jumped from. But they didn’t say. They put these flowers down but refused to answer any questions as to why. It was left unsaid. It really stirred things up. Why are they putting them there? Nothing was clear.”

“I thought they knew she went from there because they found her slipper,” I say.

“Those weren’t her flip-flops,” says Melissa. “Mike and Ann showed them to me. They were too big. They weren’t her style. They were pink and flowery and Hawaiian. I’d never seen her wear them. Why didn’t Disney come to me or her girlfriend and say, ‘Can you identify these as Bex’s?’ Instead they put them in her room for when her parents got on board. Who does that?” She pauses. “Disney swear they’ve told us everything they know, which is that they don’t know anything, but most of us think, bullshit. Someone must know something. Someone’s covering something up.”

Melissa has her own theory. “Bex was a bit of a risk taker. She was always pouring soap over people. Classic Bex. I was welcoming a family on board one time and she came over and rugby tackled me to the ground!”

Melissa thinks she went to the crew pool at 6am to be alone, with no intention of harming herself. “She loved deck 5. It’s where we always used to go. I bet she climbed on to the wall and sat on the ledge in a ‘I need to feel like I’m off the ship for a second’ way. She wouldn’t have thought, ‘It’s very high. I might fall.’ She’d have just sat on it and thought, ‘Oh crap. What have I done?’ And fell.” She pauses. “Security on that ship is ultra-tight. You can’t get on or off without your ID card. Down by the crew pool there’s HR offices, the crew gym, the crew office that deals with passports, money, documentation. And they’re saying there’s no CCTV cameras?”

“But why would they suppress that?” I ask.

“To try to protect the brand. If it was 6am and they were doing their job and watching the front, someone must have seen her go over. Or if they didn’t, they’re covering up why they didn’t.” She falls silent. Then she says, “Bex made hundreds of people happy. The passengers loved her. They all loved her. You’d think Disney would give something back. They owe it to her to find out what happened.”

rebecca-coriam.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion