MOVIES MAKE EVERYTHING LOOK WORSE THAN IN REAL LIFE.

Locking It Down

Meaghen Brown tells you which bike lock to buy and offers a primer on proper locking technique. Left alone

Left alone Watch out

Watch out Gone

GoneI used to stay up late watching the film of my bicycle being stolen. It’s amazing what you notice on the 38th replay of a surveillance tape, running the grainy recording backward and forward, pausing and advancing. Sometimes I’d back the tape up to before the 17 minutes that changed my life. All the way back to the part where I still had a bicycle.

Rewinding—past all the New Yorkers striding backward toward lunch; past the Algonquin and Royalton hotels inhaling crowds and the door of the Harvard Club admitting well-fed members; past the New York Yacht Club looming impassively like a beached galleon; past all the finery and civility of West 44th Street—you come to the beginning. You come to him.

The thief. There he is. Caught, if only on tape.

He walked into the frame on a beautiful sunny January afternoon, or what the camera mounted on the front of the Penn Club referred to as 13:29:36. He was dressed like pea bike messenger, but he didn’t have a bike. (Yet.) He looked at mine and took out his phone.

After the call, he sat on a standpipe and waited. I was inside the Penn Club, eating a hamburger and talking to my sister. The key to my lock—a foolishly thin flexible Kryptonite cable—was in my pocket.

I suppose I didn’t really believe in the little cable. Maybe I never believed in the bike, either—a blue Novara Metro hybrid. Heavy and ugly, it was the second-cheapest model in my local shop. Maybe it was the sunshine in winter or the teeming crowds or the expensive real estate. Maybe it was the hope—naive, but apparently endemic—that it would never happen to me. Not that quickly. Not in broad daylight.

At 13:40, his partner rode up, dismounted, and locked his bike up alongside mine, a standard maneuver. The lock created an illusion, a bit of street theater. Two guys, two bikes, one plan.

At 13:41, they were making a sawing motion. After a few minutes, they tried a hammering motion. Then they switched to the Brennan—named for the San Francisco man who demonstrated on the Web that jamming the soft tube of a Bic pen into some locks can open them. After a 17-minute assault, the brave little Kryptonite softie finally gave.

By my count, 142 people had walked past in that time. Only one, the very last one, tried to do anything. As the lock yielded and the thief jumped onto my bike, an elderly black man in a Kangol cap lunged for them both. But it was too late. The blue Novara vanished into traffic.

After lunch, when I discovered and reported the theft, two detectives from Midtown South arrived in minutes. The Novara—Bike One, as I came to think of it—was assigned Complaint No. 1026. I never saw it again.

Late at night, though, I would get the DVD out. The building manager at the Penn Club had burned me a copy of the surveillance footage. I’d stay up, watching the injustice unfold, freezing, advancing, making screen grabs. I learned the whole drama by heart: the approach, the call, the partner, the battle with my lock, the civic hero in the Kangol.

When I’d look up, it would be 2 A.M.

I WANT MY BIKE BACK. So do we all. With the rise of the bicycle age has come a rise in bicycle robbery: FBI statistics claim that 204,000 bicycles were stolen nationwide in 2010, but those are only the documented thefts. Transportation Alternatives, a bicycle advocacy group in New York City, estimates the unreported thefts at four or five times that—more than a million bikes a year. New York alone probably sees more than 100,000 bikes stolen annually. Whether in big biking cities like San Francisco and Portland, Oregon, or in sport-loving suburbs and small towns, theft is “one of the biggest reasons people don’t ride bikes,” Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, told me. Although bike commuting has increased by 100 percent in New York City during the past seven years, the lack of secure bike parking was ranked alongside bad drivers and traffic as a primary deterrent to riding more. It’s all about the (stolen) bike; even Lance Armstrong had his custom time-trial Trek nicked from the team van in 2009 after a race in California. Not every bike is that precious, but according to figures from the FBI and the National Bike Registry, the value of stolen bikes is as much as $350 million a year.

That’s a lot of bike. Stolen bicycles have become a solvent in America’s underground economy, a currency in the world of drug addicts and petty thieves. Bikes are portable and easily converted to cash, and they usually vanish without a trace—in some places, only 5 percent are even reported stolen. Stealing one is routinely treated as a misdemeanor, even though, in the age of electronic derailleurs and $5,000 coffee-shop rides, many bike thefts easily surpass the fiscal definition of felony, which varies by state but is typically under the thousand-dollar mark. Yet police departments are reluctant to pull officers from robberies or murder investigations to hunt bike thieves. Even when they do, DAs rarely prosecute the thieves the police bring in.

“It’s just a low priority, to be honest with you,” says Sergeant Joe McCloskey, a bike-theft specialist with the San Francisco police department who estimates that, of the scores of bicycle thieves he has caught, not one did jail time for the crime. Whether police go hard after thieves often depends on whether the officers themselves are passionate riders, like McCloskey, who at one point during our conversation geeked out over his Pivot Mach 5 mountain bike. (“The guy named it Mach 5 because, you know, Speed Racer drove a Mach 5.”) Departments that can muster a peloton, like those in San Francisco, Portland, and Houston, are generally more proactive. By contrast, NYPD officers openly discouraged me from filing reports on the stolen bicycles mentioned in this article, probably because their precincts are judged by crime stats.

It’s nice to believe, as I once did, that there is some grand conspiracy at work, that catching a few bent dealers or bad-guy whole-salers will kill the business. Over the years, there have been a few tantalizing examples of a centralized trade in stolen bikes. In Miami in the 1980s, police found six freighters in the harbor holding hundreds of stolen bicycles, possibly headed for Haiti. Many bicycles stolen in Oregon crop up in San Francisco, evidence of an export network. In California, the Border Patrol has repeatedly caught pickup trucks entering Mexico that had been stuffed with high-end bikes stolen in Santa Cruz; drug dealers there take payment in valuable bikes, which they resell to the Mexican elite.

Certainly the king of bike thieves has been found. In 2008, a quirky Toronto bike-shop owner named Igor Kenk turned out to have 2,865 stolen bikes squirreled away in his store and various warehouses. Kenk, considered the most prolific bike thief in the world, is a messy, dyspeptic Slovenian intellectual who before he was caught lived in a fancy house and associated with the classical music scene. Yet his method was brutally mundane: Kenk was finally caught pointing out bikes he wanted stolen to a mentally ill person, whom he paid with drugs. He served just over a year in jail and is already back out.

I wanted to find a Kenk, to catch those two guys from West 44th Street. Over the long nights nursing my grudge, I thought I found my solution. What if I had followed them on the day they stole my bike? What if I had shadowed them, day after day, as they fenced it? What if I had tracked their every move and knew where my stolen bike was as soon as it got there? The simple vendetta that began that day in January grew to encompass three cities, seven bikes, and repeated encounters with the dangerous underworld of vanished bicycles.

BIKE TWO WILL BE an afterthought in this story but was pivotal all the same. It was a silver Trek, heavy and scarred from city riding. We had our moments—dawn commutes over the Brooklyn Bridge, 17-degree rides during the December 2005 transit strike. But I never loved it enough to treat it carefully, and two years ago I made the same mistake I’d made years earlier with the Novara. I left it, poorly locked, behind my apartment building. Gone, baby, gone.

But Bike Two led me to act. I happened to be in Thailand a few months later and noticed a street vendor selling a small tracking device. The little gizmo, the love child of a GPS unit and a cell phone, was about half the size of a cigarette pack. Attached to my bike, it would respond to a phone prompt by firing back a location in digitized latitude and longitude. Supposedly, it could track and report continuously for days on end or sleep for weeks until, roused by movement, it would ding the satellites and report in. I brought one back from Bangkok and decided to rig my next bike with it. If—when—the bike was stolen, I’d know where it was. Then I could either steal it back or at least call the cops.

For that I needed a new bike—or rather, a not-new one. The purpose of stealing a bike, after all, is to sell it. SFPD’s McCloskey estimated that 90 percent of bike thieves are drug addicts. In America’s rough streets, there are four forms of currency—cash, sex, drugs, and bicycles. Of those, only one is routinely left outside unattended. So the story of bike thieves would not be complete without a trip through the second half of the transaction—the recycling of cycles.

Stolen bikes suffer many fates. In the Bay Area, they are often sold at flea markets, particularly in Alameda, just south of Oakland. In Portland, within hours of being taken, a few will appear at pawn shops just outside city limits, where documentation rules are lax. But just as they do in New York City, which shut down most ad hoc bike dealers years ago, the majority end up online, either on eBay or on Craigslist, the black hole of bicycles.

But how do you tell which ones are stolen? A Brooklyn bike-shop owner whose store had recently been robbed of 22 bikes pointed me toward “Bobby from Bay Ridge,” one of the most prolific sellers on the site. In a phone conversation, Bobby said he could find a bike in my size within a few days—which sounded almost like a snatch-to-order. But after riding the subway to outer Brooklyn, I found him—he’s not really named Bobby, and he does not live in Bay Ridge—to be less than sinister. He was middle-aged and living on a leafy block, with a garage full of used bikes. “I buy ’em at police auctions,” he said, mostly in New Jersey. I picked out a 1970s ten-speed—a Schwinn Continental, which would become Bike Three. It hardly had a scratch on it, meaning it was no New York City ride.

I flipped it over to look for a serial number, which is often carved on the bottom of a bike frame. Bobby blanched but recovered quickly. “It’s legal,” he said. “The police check ’em all before auctioning.”

Police departments do check all the bikes they recover against databases, but it’s a pointless exercise. The vast majority of bike thefts aren’t reported or are reported with no serial number. Bobby was just a cog in the machine.

I took Bike Three home, affixed the little black GPS tracker under the seat with epoxy, and left it locked behind my apartment, under a surveillance camera. A month later, the Schwinn disappeared.

But the Bangkok tracker didn’t work. When I dialed the number, no latitude or longitude messages came back. It had worked perfectly in tests. Maybe the tracker shorted out in the rain. Maybe the bike was stashed in the basement of a tall building that blocked satellite signals. Maybe a canny thief disabled it. Inexplicably, the surveillance camera had also failed—there was an 11-hour gap surrounding the disappearance. Only the flimsy cable lock was left behind, clipped neatly in two.

BIKE FOUR OFFERED a deeper dive into the cesspool of Craigslist. Dialing the number in a listing for a mountain bike, I reached a clueless guy named Vic. “Yeah,” he explained. “I don’t exactly have the bike. My friend does. He’s got a friend who has the bike, at a friend’s place on 14th.”

The “place on 14th” turned out to be a piece of sidewalk. We agreed on a meeting time, but he immediately called back to request that it be sooner. When I balked at the price—$200—Vic cut it by a third. Cheap, rushed, anonymous. The omens were all bad.

We met in front of an eyeglasses shop on one of the trashiest blocks in Manhattan. Vic and his partner showed up, clean-cut and well dressed—muscle men with chains and patter. They pulled the bike out of a storeroom behind the shop. It was a green Huffy Luna comfort bike. They didn’t know anything about it, not the combination to the lock coiled around the seatpost nor that its tires were flat. The bike was brand-new—it still had packing foam wrapped around the fork, and the brakes had never been connected. Vic had no explanation for this. For $140 in cash, he threw in a tool kit and a helmet.

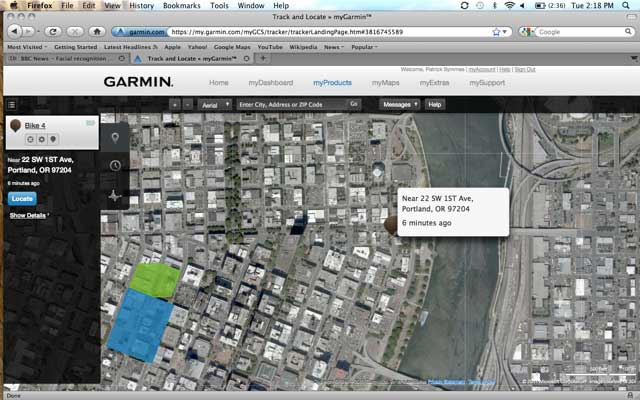

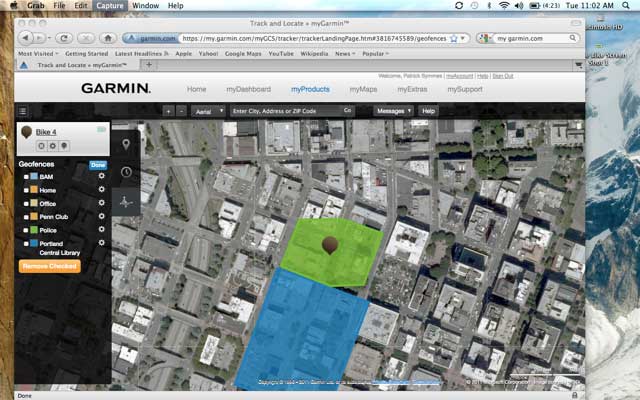

I handed over my money on the sidewalk, pumped the tires, paid my local bike shop $20 to secure the seat with a short length of bicycle chain, and attached a fancy Garmin device to the underside of it. After the failure of my Bangkok special, Garmin agreed to lend me several of its newest GPS locators, devices that allow you to keep tabs on your most prized possessions, be they children or a carbon-fiber 29er. (As gloating Web comments prove, these can also be used—illegally—to track a straying spouse.) The GTU 10 was slimmer than the Thai original—a little thicker than a pack of gum, almost invisible under the seat—and easier to track, thanks to Garmin’s slick mapping software and website. It was time for the Penn Club revenge. I rode the green Huffy into traffic for the first and last time.

I pedaled up to West 44th and, using a $20 cable lock, secured it to the same parking sign where Bike One had disappeared all those years before. For the next few days, checking from my home in Brooklyn, I could see that Bike Four was still sitting on West 44th. I’d hoped, irrationally, to catch the same two guys who’d robbed me previously, but nothing happened. A week later, I followed my wife to a temporary job in Portland and left Bike Four sitting there. The battery lasted a month, and the lock a little longer. But at the six-week mark, Peter Homberg, general manager of the Penn Club, called. An avid cyclist, Homberg had become devoted to my plot, and he relayed that the brakes had been stripped off.

Other parts began to vanish. The bike was slowly being cannibalized. When I returned in the fall, I expected to find at least the frame or a wheel. But there was nothing, not a trace. Bike Four had gone back to where it came from.

THERE HAS BEEN a war for decades, a steady escalation between locks and lock pickers. Kryptonite, which pioneered the U-lock in the 1970s, brags about its up-armored devices and has openly flattered New York City with them, first by issuing anywhere-but-New-York “anti-theft protection programs” for some of its regular locks, then by introducing the super-hardened, nearly-impossible-to-cut-with-hand-tools Fahgettaboudit series. But thieves always counter-attack with their own measures: car jacks to pry open U-locks, liquid Freon to freeze and shatter them, the notorious Brennan.

The futility of locking is shocking. We’re living in an age of surveillance and DNA swab kits; isn’t there a good all-American fix, a tool, gadget, or technology solution? Every technical panacea seems to have its own flaw. Victims of bike theft have created online registries for stolen bikes, but these are obituaries, not a way to preempt the crime. Some riders have urged manufacturers to install cheap RFID tags inside every bike they turn out, like those on clothing; with unique digital signatures, bikes would be completely traceable. But RFID tags can’t be tracked via satellite, only by handheld reader.

Pegasus Technologies, a company in California, created a long-distance system for tracking bikes, which Sacramento police installed in the handlebars of a bait bike. It worked: when the wired bicycle was stolen, police located it across town and arrested the thief. Four months later, they tried it again; the same guy stole the same bike, threw it in a pool, and left the cops a note: “You got jacked U punk motherfucker.” Pegasus now sells a similar, consumer-grade device—the Spylamp Bicycle GPS Tracker—for $178. To help avoid detection, it comes encapsulated inside a rear bike light. Which, of course, is all well and good until the thieves catch on. This past year, Kryptonite introduced a system of supposedly tamperproof security stickers, which can be scanned with a cell-phone camera for instant ownership checks. It’s a fine idea, but in our tests the stickers came off with a knife.

Maybe catharsis is all we have. YouTube is awash in surveillance-tape dramas like mine and patiently filmed revenge scenes, in which bike thieves are caught, busted, beaten, set up, tricked, shamed, and exposed, but it’s all to little or no avail. We are left with missing bikes and unlimited rage. Bike mechanics in Brooklyn can be found wearing T-shirts that read BIKE THIEVES SHOT ON SITE. It’s entirely possible that last word is misspelled.

In the end, we remain about where we were decades ago. I still rely on 1970s tech: a small hardened padlock and a three-foot length of hardware-store chain. For others, the most salient fact about a lock is not its strength but its convenience. The burden of big locks deters many people from riding, while others turn Kryptonite’s heavy-duty chain into a fashion statement, belted around the waist. (Don’t lose the key.)

Oddly, the sanest strategy I’ve encountered was outlined by musician and devoted rider David Byrne. In his quirky memoir Bicycle Diaries, Byrne advocates for folding bikes, which can be put in a closet. For the rest of us, he recommends security bolts on the wheels (harder to remove), smaller U-locks (harder to pry open), and cheap bikes (because everything gets stolen).

PORTLAND BILLS ITSELF as Bike City, USA. Like any new citizen, I needed a ride in my adopted city. The day after arriving in town I spotted a trio of dubious bike salesmen in the Southeast neighborhood. A line of 20 battered bikes and things like dishwashers and toaster ovens were for sale in front of their house. A transvestite with heavy face glitter sat on the curb, hawking the goods while knocking back malt liquor at 11:15 A.M. The shop assistant was shirtless, and the boss was a disabled man strapped into a wheelchair, plucking bike parts from buckets of spares arrayed around him—crates of grimy handlebars, dozens of cables, rows of wheels stripped from other rides.

To help conceal their identities, stolen bicycles are often converted into Frankenbikes—quick, haphazard rebuilds—which was likely what was going on here. I focused on a purple Giant Yukon. (“It’s your color!” the transvestite said.) Their negotiating tactic was to give in: they asked for $190 until I frowned, whereupon the price became $170; more silence brought it down to $160; when I started to walk away, they let it go for $70.

The Giant was a junker, but within an hour I had duct-taped a Garmin tracker beneath the seat and was headed down the Spring-water Corridor bike path to downtown Portland. On the way, I detoured through an area recommended to me by Portland police detective Joe Luiz. When I met him, Luiz, a devoted cyclist who had just returned from riding in the wine country of Walla Walla, Washington, had discussed the futility of many locks and then directed my attention to a freeway underpass along the Willamette River. I found the spot, home to dozens of homeless people in a semipermanent encampment. Most had bicycles; some had three. But Luiz and his colleagues were almost powerless here: for public relations reasons, police usually warn occupants in advance before searching the camp, which kind of nullifies the effort.

Luiz had also tipped me off to my final destination, Portland’s Central Library, across the river in the heart of downtown. Bikes vanished there all the time. I left the purple Giant unlocked and propped against a mailbox, at SW 10th and Alder, about two blocks from the library and its benches crowded with vagrants. I stepped across the street to the Governor Hotel, ordered a glass of Walla Walla white, and sat in a picture window, laptop open, camera at the ready. After two hours, I was briefly distracted. When I looked up, the bike was gone.

In the Wi-Fi bubble at the Governor, I watched on my laptop as my stolen bike progressed north and then east through downtown. Every few minutes, I pinged the GPS tracker, which got a fix and popped a marker onto the site’s map. Book ’em, Danno! Here was my stolen-bike fantasy brought to life, the unknowing thief tracked from the sky, his every move revealed in real time:

5:05 PM—at 303 SW 6th Ave less than a minute ago

5:11 PM—at 426 W Burnside St

less than a minute ago

5:13 PM—at 201 W Burnside St less than a minute ago

5:16 PM—NW Naito Parkway & NW Couch St less than a minute ago

Eventually, the thief decided to leave downtown and headed over the Steel Bridge, an ugly double-decker from 1912 with extra-wide bike lanes. But at 5:23 P.M., he changed his mind and returned to the west side. By 5:40, he’d pedaled south, .61 mile, to the Morrison Bridge, moving slowly (“1 MPH,” the GPS reported) but still moving. The Morrison Bridge points directly to that bike-dense homeless encampment I’d visited, but the thief seemed in no hurry to get there.

5:46 PM—at 82 SW Naito Parkway

5:50 PM—at 28 SW 1st St

He circumnavigated the Saturday Market, a spot for craft vendors, three times, but around 6 P.M. the readings became consistent. He was riding up and down the Waterfront Bike Trail, a green esplanade between the bridges. When I saw this pattern—north, then south, then north, at just 1 mph—I feared he was trolling for customers. I paid my bill and dived into a taxi.

AS WE APPROACHED the river, I no longer had a Wi-Fi signal. The Garmin unit works with some cell phones but not with mine, so I just picked a random point and told the cab driver to pull to the curb.

The very first thing I saw—seconds after exiting the cab—was a bearded white man on a familiar bike. He almost crashed into me. Indeed, he had to swerve to avoid me and nearly took out the fellow he was talking to.

When I’d told Luiz and his colleagues what I was up to, another detective had texted me: “If you need police help call 911 and we will figure out a mission to help in an undercover capacity. Have fun and be safe.” I’m no vigilante, and you really should call the police the moment you figure out where your bike is. But I was unprepared. Instead of being safe, I decided to have some fun.

The thief was talking to someone, and the only word I caught was “silver.” So, apropos of nothing, I blurted out, “Hey, are you into silver?” He stopped, and I launched into a nervous monologue. About silver. About colloidal silver. Silver prices. The color silver. Anything I could think of. It was idiotic but successful. The thief made conversation. Yes, he was into silver, he told me. Yes, he said, to whatever I said. He agreed completely.

After some crazy talk, I realized that the thief wasn’t just acting crazy. The silver was all hidden somewhere, he said. At the bottom of the ocean. He’d nearly died at the bottom of the ocean while in the Navy. He was in fact the legitimate son and heir of King Richard III. A trillion dollars in gold and silver—“All that money in the U.S. Treasury”—actually belonged to him.

This continued for about five minutes, until I pointed to the bike helmet tucked under my arm, and then the Giant Yukon he was riding. “I have a helmet,” I observed, “but no bike.”

“Oh,” he said, visibly deflating. “How did you find me so fast? It’s GPS, isn’t it?”

He didn’t mean my GPS, which was still pinging the satellites from under his rear end. He was schizophrenic, it seemed, and presumed he was always being followed. He got off the bike and handed it to me. We parted without drama.

I rode south for four miles, letting the grind of the pedals help my thinking. Richard IV was a thief but the wrong kind. He needed help, not vengeance. GPS units and police patrols and thick chains would never stop the lost legions of our streets.

This sad truth was reinforced when I later put Bike Five back on the street. I locked it this time, to avoid picking on someone like Richard IV. Yet no Kenkian mastermind or West 44th Street bad boys came to light. The bike just sat there, for days, then weeks:

Latitude: 45.51983498968184

Longitude: 122.68337331712246

Speed: 0 mph

After a month, the wheels had been removed. A few days after that, just after I removed the tracker, the seat was taken. Then someone who needed a fix stripped off the brakes. Bike Five—nothing left but a trapezoid of tubes—is sitting in my garage right now.

BIKE SIX, I LOVED YOU at first sight. Plucked from the streets of San Francisco, you were the finest I ever had, although that isn’t saying much.

Over the years, Sergeant McCloskey had launched dozens of stakeouts, stings, and reverse stings against bike thieves in the city’s Tenderloin District, becoming a legendary Lone Ranger in the bike wars, a one-man encyclopedia of cycle crime. He once spent an hour telling me his favorite techniques for catching thieves. The best spot was the San Francisco Public Library’s main branch, a few steps from Market Street. “We took a nice Cannondale and locked it to the bike rack there, set up a robbery detail, and watched the guys stealing the bikes,” he explained. “It worked really well. They’re very slick. They ride up on their own bike, park next to it. They have bolt cutters on a shoelace around their neck and lean down to cut it. They’re very fast. We did this successfully more than 20 times. We’ve only been skunked once. About 90 percent of the people we get are drug addicts, meth heads. Speeders, we call them.”

In Portland, Joe Luiz had confessed that he’d never quite figured out where all the bikes were going, but in San Francisco this wasn’t an issue. Stolen bikes were for sale, openly, at Market and 7th, a block from where Sergeant McCloskey got so many stolen.

I’d come to San Francisco for a funeral—my father-in-law had passed away. I drove downtown to pick up his ashes and, combining two errands into one, drove down Market Street to buy a stolen bike. I parked and walked to the corner of 7th, where there was an open-air market in fenced goods, from canned food to blue jeans to batteries. Within 60 seconds, a kid rode up on a black single-speed and smiled at me.

He wanted $175. When I bargained, he said, “It’s a $700 bicycle. I looked it up.”

We finally agreed on $125. As I counted out my money, two other bike deals were going down at the same moment. One, involving a delivery bike with a basket wired to the front, started to go bad, heading toward a fight. I shoved the cash at the kid and sprinted away on Bike Six.

Minutes later, I was driving around San Francisco with a stolen bike in back and my father-in-law’s ashes up front. The bike was beautiful—an IRO track bike, designed and built in Pennsylvania, with a flip-flop hub, slim handlebars, and a tiny leather seat. There was a serial number on it, but when I checked registries of stolen bikes online, no one in San Francisco—or anywhere else that I could find—had reported it missing.

The hot-bike market in downtown San Francisco was shameless, a disgrace to the city. But it wasn’t the Bay Area’s only dubious bicycle venue. The Alameda flea market was notorious for recycling stolen bikes, and in Golden Gate Park there was a chop shop where amateur mechanics swapped components and resold stolen bikes for profit.

I rode the IRO through verdant Golden Gate, enjoying the smooth ride. I’d always thought single-speeds were an illin’ pose, but the IRO was nimble and ridiculously light. Standing on the pedals, I climbed past 15-speeders in my only gear. It was like having a skinnier, younger girlfriend. I never found the chop shop or carried out my plan to sell the IRO. Later I called Sergeant McCloskey and told him about the track bike.

“You got burned,” he said. “You paid $25 too much.”

I put the IRO back in the car, near the old man’s ashes. I still have it, and I ride it everywhere, but I need to go straight. If you lost one in San Francisco, contact me with the serial number.

I NEVER OWNED Bike Seven, a.k.a. the Last Bike, which belongs (still) to the Portland police’s burglary task force. But it was an impressive machine, a brilliant silver Trek triathlon bike, valued at about $1,500. Not coincidentally, this sum qualified it as a felony theft in Oregon. It was light as a feather, despite the elbow rests and gear changers mounted on the upright bars.

At the Central Precinct one morning, Officer Hilary Scott, one of Detective Luiz’s colleagues, handed over Bike Seven, allowed me a few minutes to install a GPS tracker under the seat, and then walked me out of the building. A fellow committed rider, Scott gave me precise instructions on where to lock it up, and I set off through traffic, bugged and tailed, for Operation Steal My Bike.

I’d never ridden with aero bars and nearly smeared myself across a police cruiser before discovering there were no brakes up there. Only one gear worked. The robbery squad rides poky bikes, and they had disabled the bait bike’s other gears—they didn’t want to be outsprinted by some meth head channeling Mario Cipollini.

Eventually, I struggled up to the address Scott had picked. It was only half a block from where my Giant Yukon had been stolen by Richard IV. About 1,100 bikes had been reported stolen in Portland that year, some 600 of them here in the Central Precinct, and most of those within a short ride of this exact spot.

I locked up the bike, badly. Six cops were out here somewhere, watching in plain clothes. But I’d met only officer Scott. So where were the cops who supposedly had my back? Across the street was a fisherman-type guy in a blue windbreaker. He was waiting with a bike at a streetcar stop. A streetcar came and went, and he was still there.

My phone rang. From offstage Scott was watching me lock the bike. She had me change its position. Then she sent me to a Starbucks up the street while she stood by with a recovery team, uniformed officers charged with nabbing a thief.

A couple of hours went by. I drank too much coffee. Occasionally, I poked my head out into the street or walked around the block. The Fisherman in blue was still there. Who else was on the job? The guy in the white grocer’s smock? The happy couple laughing as they adjusted their bike helmets?

I logged on to the coffee shop’s Wi-Fi, and my laptop revealed the tracker’s position from all of a block away. I set the Garmin software to report every 30 seconds and to send me a text message if the bike moved.

Scott called. Cops get lunch breaks, and we quit for 90 minutes. I rode the fussy Trek back to my car. En route, bouncing up SW 3rd Avenue, I noticed the happy couple pedaling along behind me. They made a left turn, toward the Central Precinct.

WE DIDN’T catch anyone in the afternoon, either. We did a second shift, a few hours in different spots around town, ending at one of the sleaziest areas in Portland, under the bridge. The street was full of homeless people, addicts, preachers, drunks, the curious, the insane. I locked the bike—using a $5.99 kids’ model. Fisherman rode past on his bike, dismounting and pretending to make a phone call.

I got a coffee, checked the tracker, and glanced down the street. The happy couple was out there now. An hour later they’d separated, and Mrs. Happy Couple was chilling with the Fisherman instead. The police bike was sitting patiently, waiting to be stolen, the fate of all bikes.

Until the cannibalizing of Bike Four, I was optimistic, convinced that bike theft could be stopped by technology. Bike Five’s demolishing left me burned out, believing there’s little we can do about bike theft. Bike Six gave me back my joy, just as Bike Seven restored my resolve. This is a war of attrition. Like the police, we can and must resist, even when it’s futile. I’m still pimping around Portland on Bike Six, my little black IRO, with 11 pounds of chain wrapped around my waist and hex nuts on my wheels. All the partial solutions—a national bike registry, better serial numbering, more secure parking, GPS trackers disguised like bells and reflectors—are getting better. We aren’t going away.

Unfortunately, the thieves aren’t either. When I arrived back at Central Precinct, Mr. Happy Couple was in the robbery squad’s tight warren of cubicles, stripping off his sweaty gear and laughing about something. As he’d left the scene of the stakeout, an agitated man had called over to him.

“Hey,” he said, “I just had my bike stolen!”

I know how it is, brother. So many bikes, so little time.