Published in the February 2012 "Things We Can All Agree On" issue, on sale soon

The guys were coming over. That's what Fred and Charlotte Thomas both called them — "the guys," as though they were Fred's poker buddies. Fred and Charlotte were both in their early seventies. They were retired. They were living in a place that was still new to them, and in some ways still foreign. They weren't in the best health — Charlotte had pain in her legs, and Fred, just a month before, had endured having half a lung removed by doctors who had misdiagnosed him. They thought he had cancer, when in fact the growth was a fungus. Fred had lost half a lung by mistake, and now both Fred and Charlotte had trouble climbing the stairs in their tall, narrow house. It had been a tough year, and when Fred told her that the guys were coming over, she was just happy he had friends.

It was March 17, 2011, when they came over the first time. Saint Paddy's Day. Charlotte and Fred had gotten some pizzas and beers so they would have something to eat. Then she went upstairs, to leave Fred alone. Or maybe she went out. She doesn't remember. She didn't know that many of the guys, anyway. Oh, she knew Dan — Fred's friend Dan Roberts. The rest of them were new. There was a guy named Anthony, and another guy whose name she forgot. There was a guy named Joe, and then there was Joe's son, also named Joe. The first Joe was much younger than both Fred and Dan — at least twenty years younger — and the second Joe was just twenty-five. Well, Fred and Charlotte were used to that. They were used to having younger friends.

The meeting went well. The men talked, ate, laughed, and went home. Fred talked a lot, but then he always did. Charlotte couldn't imagine — who could? — that one of the guys was wearing a tape recorder, and that when the meeting was over, he gave the tape to a Department of Homeland Security agent named Scott Matthewson, who had staked out her house and was waiting nearby. And she couldn't imagine that when Matthewson listened to the tape, he'd hear her beloved husband saying what would make him notorious:

"There is no way for us, as militiamen, to save this country, to save Georgia, without doing something that's highly, highly illegal. Murder. That's fucking illegal, but it's gotta be done."

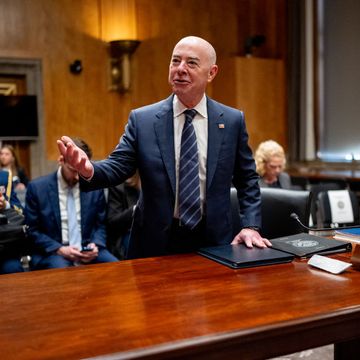

It's amazing whom we're arresting as terrorists these days. Fred Thomas, for instance, top left, is seventy-three years old and suffers from both heart and kidney disease so severe he can't walk up the stairs in his house. He's U.S. Navy — retired and spent his life working for defense contractors. His coconspirators are, clockwise, Samuel Crump, aged sixty-eight; Ray Adams, aged sixty-five; and Dan Roberts, aged sixty-seven.

Now, I've been to that house. I went a few weeks after Fred Thomas, seventy-three, was arrested — along with Dan Roberts, sixty-seven; Samuel Crump, sixty-eight; and Ray Adams, sixty-five — for conspiring to commit acts of terror in what became known nationwide as the case of the "geriatric jihadists," or the "grumpy old terrorists." I live in Georgia, about ninety minutes away from the mountain town of Cleveland where the Thomases live, and like everybody else, I was interested in what seemed like the two big disconnects in the story, the first between what the conspirators allegedly planned to do and what they seemed capable of doing, and the second between the utter familiarity of what we read of their lives and the utter unknowability of their dreams. They'd become famous for having some of their meetings in a Waffle House and a Shoney's — famous, that is, for doing what codgers do in every community in America, and for making Americans wonder, for a moment, if instead of "solving the world's problems," as the codgers like to say, the codgers might really be talking about blowing it up.

I couldn't imagine how hauntingly familiar Fred and Charlotte's life was, though, until I went to their house in Cleveland. It's a house on a dirt road, with a yellow DON'T TREAD ON ME flag flying in the front yard — a description that conveys almost nothing about either the house or the life that Fred and Charlotte enjoyed inside of it, because it conveys a kind of angry hillbilly primitivism. The Thomases aren't hillbillies. They're Yankees. They had retired to Georgia three years before, after living the last thirty years south of Washington, D. C., serving the federal beast. They had chosen Georgia to be close to their son and his family, and because Fred was a hunter — yes, a gun nut, with a collection of fifty firearms, some of them valuable — and loved the mountains. Their house was a house on a dirt road in the same way that the cute country store that sells souvenirs and homemade jellies is a real country store. It's a fantasy of a Georgia mountain house, or, as the Thomases prefer to call it, a "dream home," since they invested most of their savings in it. Sure, it's meant to look rustic, fashioned inside and out of unpainted wood, but it's also three stories tall and part of a development whose office is open for business a couple of houses down. It's decorated with the modest adornments requisite of modern American retirement — prayers and prints of angelic children on the walls, along with humorous reference to who really rules the roost — but it's also highly individualized by Charlotte's adoration of two men: Frederick William Thomas and Francis Albert Sinatra.

The Sinatra thing killed me, I have to say. You pull into the Thomases' driveway and you're greeted by a sign that says, FRANK SINATRA FAN PARKING ONLY. ALL OTHERS WILL BE LEARNIN' THE BLUES! You're greeted by a timorous black cocker spaniel named Frankie. And you're greeted by Charlotte herself, dressed in maroon sweats, smoking a cigarette and drinking coffee from a Christmas-themed mug. You follow her into the house, and the first room you enter is a shrine to Ol' Blue Eyes in his American Century glory, a room wallpapered with vintage album covers and a big poster of Frank and Dean and Sammy standing in front of the Sands in Vegas. In the middle of all the paraphernalia, there's a small framed black-and-white photograph of Sinatra singing at the Sands, smoky and moody, very dark except for the glimpse of a woman's bare crossed leg, catching the spotlight up front and stage left. "You can't really see, but that's me," she says, pointing to the spotlit leg. "I was on my way out to California to marry Fred, and I stopped in Vegas to see Frank."

And there it is — the conflation of two men whom Charlotte Thomas has loved most of her life. She was seventeen when she met Fred. Fred was nineteen, freshly enlisted in the Navy. "The first thing that attracted me to him was his confidence," she says. He was a little guy with a straight spine and a banty strut, a commanding runt who was never shy about saying what he wanted and how he was going to get it. She met him at a movie theater in Waukegan, Illinois, and she might as well have met Sinatra himself — "I knew the minute I met him that he was the one for me. We've been married for fifty-one years, and he is my life."

You know these people, then. I do, at least — I grew up among people just like Charlotte and Fred, people with realistic hopes and romantic dreams, and a look of care even when they're supposed to be at ease. Charlotte might have been one of my relatives or a friend of my mom's, with her hair cut short and tinctured ginger, her hands divided between coffee and cigarettes, and her mouth cratered by worry. She had plenty to worry about, of course; just a month before, the FBI had broken down the unlocked door of the Sinatra room and thrown flash grenades on the floor, and both the door and the floor still bore the scars and the burns. And then the phone rang. She picked it up and said, "Hi, hon" with such hard-won reflexive intimacy that it was easy to forget, if only for a second, that her husband was calling her from the Hall County Jail, in Gainesville, Georgia.

He was, though, and that's the thing. Fred Thomas was in jail with his alleged conspirators for plotting to assassinate government workers and public officials, to blow up government buildings, and to manufacture and then distribute a sort of moonshined poison called ricin for the purpose of killing as many of his fellow Americans as possible, thus provoking a civil war and a return to "constitutional" government. He had spent fifteen years in the Navy as a communications specialist, and his service included a stint under the polar ice cap in the nuclear submarine James Madison. He worked as an engineer for federal contractors like Sperry, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin and was given, according to Charlotte, "top-level security clearances." He had served not only his country but also his government, and he was the father of two and grandfather of five. He had never committed a crime. Now he was in jail for a crime he might not have been able to commit — for dreaming it, thinking it, planning it, and taking what the government calls "concrete steps" to carry it out. Of course, he never did carry it out, thank God, because of the government's policy of preemption — because the FBI found out that he was in the grip of a murderous fantasy and stopped him before he could make it real. But Fred Thomas was also in the grip of something else besides fantasy, and what he was also in the grip of was the government that used its resources to make his fantasy real so that it could stop him from carrying it out. He was in the grip of a confidential informant who, over an eight-month period, kept calling him and coming to his home, and sat at the very table where I sat with Charlotte Thomas and drank coffee from a Christmas cup. And the confidential informant worked for the government — no, he worked for us, though we're not supposed to know who he is or the nature of his résumé.

Fred Thomas had never committed a crime before the confidential informant came to his house and taped his conversations and turned over the tapes to a DHS agent who, in the language of the search warrant that preceded the broken-down door and the flash grenades in the Sinatra room, "remained in the area" of the Thomases' dream home while the confidential informant ate Charlotte Thomas's homemade lemon bars. Now Fred Thomas stands a good chance of dying in jail. This is not to say that he is entirely innocent, for to watch the plot he conceived unfold over time is to watch a familiar man become gradually unknowable. But he is pushed and prodded along the path of unknowability by two entities that are unknowable by design — by a confidential informant fresh out of jail, and by the government that employed him.

The confidential informant is no longer confidential. His name was mentioned at a bond hearing for Fred Thomas and the other guys. It's Joe Sims, and it turns out that a lot of people knew him. The families of the conspirators knew him, obviously, and spoke cringingly of having met him. The wives and children he'd left behind knew him, because he's not the kind of man they were likely to forget. Men and women associated with militias in Georgia and South Carolina knew him, because he's a social guy who prides himself on his connections. And the law knew him, because he was facing six counts on a pending case and it was their business to keep track of him.

That didn't make him any easier to find, however. For one thing, militiamen have an inordinate love of the cloak and dagger and don't like to give out phone numbers. For another, although Sims was a longtime resident of Anderson, South Carolina, and a spine of small surrounding towns, his main militia association was with something called the Militia of Georgia, Toccoa Unit. For another, people associated with him have a tendency to go out of circulation for a while, as when I tracked down a man said to be his friend and sidekick only to find out that the man had pleaded guilty to sexual assault in 2008. And for another, my being able to contact known associates of Joe Sims didn't guarantee that they were happy to hear from me.

One of them was a man named Dean Suttles. He was supposed to be Joe Sims's best friend a few years back. He served with Sims in a volunteer unit chartered by the state of South Carolina called the South Carolina State Guard. Now he lives in Iva, South Carolina, to the south of Anderson, next door to Joe Sims's parents. He's married to Joe Sims's first wife. I called him and told him I was writing a story about Joe Sims, and he asked, "Which one?"

I said, "Joseph Harold Sims."

He said, "Which one?"

I said, "Junior."

He said, "You're writing an article about Joe Sims Jr.?"

I said I was. When he'd answered the phone, he'd spoken in a wary country-boy baritone, and he sounded like Elvis with a vestigial stutter. Now his voice rose to a theatrically offended tenor. "You're going to write an article about Joe Sims? Why you want to waste paper on scum like that for? That man is scum. No, he's lower than scum. I don't know what's lower than scum — maybe a snake. But he's scum, and if you're writing an article about him, then you must be scum, too...."

As it turned out, he didn't believe that I was writing the story for Esquire. Hardly anybody did. When I visited Sims's bail bondsman, he evinced extreme displeasure at my showing up at the front door of his home. He was about five and a half feet tall, an ex-bantamweight bodybuilder with a flattop and a holstered gun. He said, "You better change your story, man."

I said, "What do you mean?"

He said, "C'mon, man. It doesn't add up. You're here for Esquire magazine? You gotta do better than that."

I said, "Why would I come all the way out here to talk about Joe Sims if I wasn't writing a story about him?"

He said, "I can name about ten reasons for coming out here and talking about Joe Sims, and none of them have anything to do with a magazine article. C'mon, man. Change your story...."

And that's the way it was with Joe Sims. It wasn't so much that he had a way of making himself scarce but rather that people had a way of wanting him to be scarce, as in the case of the Georgia militiaman who says that when Sims sent a message inviting him to one of the meetings, he didn't go because Sims had stayed at a house a few years before and had stolen $4,000 and a collection of valuable arrowheads. He left not so much a trail as a nighttime sheen, but still I managed to find out some things about him.

He was forty-six years old. He was a shade under six feet tall and about 180 pounds. He worked delivering pizzas and repoing cars. About a dozen years ago, he was a volunteer fireman in Iva and rode around in a red truck with the word FIREFIGHTER on it. He faced some charges of falsifying information on gun applications and also of possessing a sawed-off shotgun, but the charges were dismissed. He had a tattoo of a tree and an ax on his left arm. He was balding on top and always wore a cap. When he was eighteen, he married a fourteen-year-old girl. He cheated on her extravagantly, and then one day, while performing his duties for his company, JoJo's Repo, he met a woman named Leann. She worked for a loan shop in Anderson, and he took up with her and wound up marrying her.

Unlike his first wife, Leann was a grown woman, and she had two daughters. One of them was around eleven when Joe and Leann got married in 2000. The other was younger. In early 2010, the younger daughter went to the Anderson County sheriff with a complaint that Joe Sims had molested her. After his home was searched and his computers impounded, Sims called the sheriff's detective. He said, "You can take anything you want, you ain't going to find nothing." The search of his computers revealed what the arrest warrant describes as "multiple photographic images ... which depicts minors in various stages of undress and also engaged in sexual activity." In March, the sheriff's detective called him and told him that he had twenty-four hours to report and face arrest. He didn't show. A day later, he was stopped in Maryland, on Interstate 95, for a missing tag light, and brought back to Anderson. On March 25, 2010, he was charged with six counts of sexual crimes starting in 2002. They included the molestation of minors and the dissemination of child pornography to minors, as well as having "carnal intercourse" with his stepdaughter: incest.

Sims's bond was set at $46,000. He couldn't make bond. He went to jail and stayed in jail for seven months. He says that he started trying to contact the FBI almost as soon as he was incarcerated but that the Anderson County Sheriff's Department blocked his every attempt for more than three months. It was July 2010 before a letter from Joseph Sims reached the FBI office in Greenville, South Carolina. Although he had been in jail since March, Sims said that he knew of a plot to blow up buildings in downtown Atlanta. A month later, Scott Matthewson, an agent for the Department of Homeland Security assigned to the Joint Terrorism Task Force in Atlanta, called Gregg Hayden, the sheriff's investigator who had signed the warrants for Sims's arrest. Matthewson told Hayden that a militiaman was in his jail and that Matthewson wanted to interview him. He did, several times — Hayden remembers four — and arranged for Sims to be polygraphed. Sims took the polygraph in August 2010, and failed. Matthewson thanked him for his time and didn't come back. But two months later, Sims still got out of jail. Despite his being unable to make bail since his arrest, he — or, he says, his sister — was able to find a bail bondsman willing to take out a surety bond on him, despite the bondsman's personal policy against bonding out sex offenders. Joe Sims had been considered a fugitive; he was jobless; his ex-wife Leann filed for a protective order against him the day after he got out of jail; he began engaging in regular traffic across the border between South Carolina and Georgia — and yet his bail bondsman says, "I consider him a minimal flight risk. One of the best risks I have, as a matter of fact. I know where he is every second of every single day, and there's only one other person in the world that can say that."

Sims says that the person to whom the bail bondsman refers is not a government handler but rather a close friend who's keeping his secrets and "has my back" in case "I disappear or go to jail on some funky charges." He also says that the government had absolutely nothing to do with his making bond, and both the Justice Department and his bail bondsman back him up. But the fact remains that as soon as he got out of jail, he went back to Scott Matthewson. This time he didn't tell Matthewson about a plot; he told him about an individual, and Matthewson decided the individual was worth watching — so worth watching that it was worth having Joe Sims watch him. Sims signed on as a source with the FBI in December 2010. Around the same time, he was supposed to report to a meeting with the public defender. He never showed. He was a free man. He remains a free man, with a case still pending almost two years after his arrest and no court date set, and so I called the former Leann Sims for comment. This is what she said, pretty much in its entirety:

"He's my ex-husband and he molested both my daughters. That's all I'm gonna say. He's a bad man and he's done very bad stuff."

My phone rang the same time that Charlotte's did. We were at her table, and she got up to answer hers with a "Hi, hon" for her husband of fifty-one years. My screen showed: "Unknown." Five minutes later, it rang again: "Unknown." I had found an e-mail address for Joe Sims the day before, on an online message board for one of the militias, and I'd written him with a request for an interview. I didn't think that he, as a confidential informant, would ever answer. Now I checked my messages and heard this:

"You sent me an e-mail about the Militia of Georgia. I'm a very cautious person. I'll call you back in five minutes with another blocked number."

And then this: "I've called you twice. Write me an e-mail and tell me when you can take a call from a private number. I'm not going to give my number out to a total stranger. Thanks."

It was Joe Sims, and when Charlotte returned to the table, I asked her about him. "I only remember meeting him once," she said. "Fred had some of the guys over, and Joe Sims was sitting right here. He was interested in all the Sinatra stuff. Then when he was leaving, he said something to me. He said, 'The one problem with that collection is that Frank Sinatra can't sing.' I said, 'Excuse me?' He looked me right in the eye and said, 'Frank Sinatra can't sing.' The hackles on my neck stood up. Literally. I mean it. When Fred came back, I said, 'He's bad news, Fred. I can tell you right now, he's bad news.' But Fred pooh-poohed it. He said something like, 'Ah, you don't know what you're talking about.'"

It is the central mystery of the case, one even more perplexing than the mystery of whether the old conspirators would ever have been capable of doing what they were talking about doing, or whether, if they weren't capable, they could be guilty of any crimes. By all accounts, Fred Thomas had lived an exemplary life of loyalty and leadership, with a devoted wife, a son nearby, a secure pension income, and a dream home to show for it. Joe Sims, by all accounts, had lived a slippery and slovenly life that made him the equivalent of his cell-phone stamp — unknown. He was a man of unsavory associations and catastrophic divorces, a man who when he tells the truth, tells it slant, a man who stands accused of raping his stepdaughter in a house with her old swing set still planted in the backyard.

And yet Fred Thomas called him and still has his phone number on his speed dial. When Sims called Thomas, Thomas picked up the phone, and even when Charlotte took an icy message, Thomas always called Sims back. The moral order was reversed: The old man who had committed no crime fell under the sway of a much younger man who was already charged with the kind of crimes synonymous with a betrayal of trust, indeed with evil itself. Through the government policy of preempting terror, of making terror happen in order to stop it from happening, the alleged author of a crime from which people instinctively recoil — incest — gained moral advantage over the alleged author of a crime that did not yet exist. What's more, the younger man was given every possible resource to work toward the fruition of the hypothetical crimes of the older man in order to keep his own ass out of jail. It's a kind of madness, and yet Charlotte Thomas didn't see that Fred Thomas was going along with it. Oh, she saw Joe Sims enough to know that she didn't like him. But she could never see that in some ways Joe Sims knew her husband of fifty-one years better than she did.

He had become a little old man. The "little" part he could handle; Fred Thomas had been small all his life, and had countered it with a rigorous self-belief. The old part was harder. He was sick, for one thing. He had kidney disease. He had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He dragged around a tank of oxygen everywhere he went. He had two flights of stairs in his new house and couldn't make it up either of them without stopping halfway. He had torn rotator cuffs and couldn't lift his arms over his head. He had always been a man of action, and now he was enduring the irrelevancy of old age in a place where he was unknown. He retired from Lockheed Martin on June 1, 2008, and moved from his home in Fredericksburg, Virginia, to the new house on the dirt road in Georgia a month later. Charlotte insists that he loved both his retirement and the place to which he'd retired; that his son and his family lived not an hour away; that they spent their days together, exploring the quaint nearby towns, like Helen and Dahlonega, and working in the garden. "Oh, he loved it," Charlotte says. "We love it. We still do."

No, he didn't sleep very well. But then, he never had. He'd always been a night owl, Charlotte says, and now in retirement he had the chance to stay on the computer into the morning and sleep late into the day. He did not tell Charlotte what he did on his computer; she did not ask, nor think to. He had never been one to keep secrets. But he had one now. He'd developed a disease more wasting even than the disease that caused him to drag around an oxygen tank like a cold metal curse. He couldn't tell Charlotte about it, though, for the disease was regret. He was alone with it, and two nights before Christmas 2006, he shared it in a post submitted to the online forum of his old nuclear submarine, the James Madison. It was called "Reflections," and he wrote of having been young and "seeing older people through the years and thinking that those older people were years away from me and that winter was so far off that I could not fathom it or imagine fully what it would be like....But, here it is...wife retired and she's really getting gray...she moves slower and I see an older woman now. She's in better shape than me...but, I see the great change....Not the one I married who was young and vibrant...but, like me, her age is beginning to show and we are now those older folks that we used to see and never thought we'd be.

"Yes, I have regrets. There are things I wish I hadn't done...things I should have done. But indeed, there are many things I'm happy to have done. It's all in a lifetime....So, if you're not in your winter yet...let me remind you, that it will be here faster than you think. So, whatever you would like to accomplish in your life, please do it quickly!"

He had an answer to the disease of regret, however, and it was the same answer that a lot of men find, especially through the Internet: fantasy.

He'd always been a "conservative Republican," his wife says, who'd gone from Limbaugh to Hannity to Beck, and now started commenting on the Web sites of those who shared his enthusiasm for guns and for Second Amendment absolutism. One he enjoyed in particular was the blog of a former Alabama militiaman named Mike Vanderboegh, who not only wrote for "the 3 percent" of Americans who would shoot back when the government comes to seize their guns but also began posting chapters from his novel Absolved. Styled by Vanderboegh as a "warning," the novel is instead an exercise in wish fulfillment in which virtuous gun owners start a civil war by resisting the effete, decadent, and inevitably corrupt forces of a collectivist government out to steal the weapons that are the only true emblems of a free citizenry. It is no accident that an overwhelming technical facility is the great equalizer between the gun owners and the government, nor that most of the book's heroes are fat, sick, and old.

It was not long before Thomas found the Liberty Forum, which is the message board of the Militia of Georgia. Mostly under the name "Ahab627," he began posting sternly eloquent warnings about government tyranny, and also writing of "hypothetical" situations by which fictional dreams might be realized. Two days before Christmas 2008 — and almost two years to the day after posting about his disillusion watching himself and his wife grow old — he became a man of action again through an act of imagination. While denying actual intention, he envisioned the ease with which the United States government could be overthrown by a program of "patriotic assassinations" carried out by groups of five "committed citizens" executing "lightning strikes" against "problem" politicians. He was not disciplined for this by the moderator nor rebuked by other Liberty Forum posters. Instead he was praised for his "gonads," and finally, on January 2, 2009, six months after moving to Georgia and eighteen days before the inauguration of Barack Obama, he celebrated the New Year by joining the Militia of Georgia, also known as the MOG:

"My name is Frederick W. Thomas RMC (SS), USN, Ret. and I'm new to this forum. I've seen the handwriting on the wall and I believe what I've read. Most of my adult life has been spent in service to America, and here in the twilight of my years I find that my sacrifice and the blood I've shed for this country has led to the enslavement of me and mine. The Constitution I swore to uphold is being abrogated by the very government that called for service and I wonder if there will be my America much longer.

"I've decided I can sit idly by no longer and so freely join with you to do something about this intolerable situation. If membership here-in makes me a member of the Militia of Georgia, then I've succeeded."

He worried that he was too old for membership; he needn't have. He'd stumbled on the secret of the militia movement: that it ignores virtually every reality but the self-actualizing realities of the Internet. It didn't matter that Fred Thomas could barely hold a gun, much less shoot one; he could post, couldn't he, and so he discovered what Jimmy Wynn, the nominal "commander" of the MOG, had discovered ten years earlier, when, as he says, "the message board replaced the meeting, and suddenly anybody with a keyboard could call himself a militiaman." Wynn discovered this the hard way when Joe Sims came across the river from South Carolina. After he won an election that displaced Dan Roberts as "captain" of "the Toccoa Unit" of the MOG, he set his sights on Wynn. "Joe Sims was a little more tech-savvy than I was back then," Wynn says, "and he wanted to start a Militia of Georgia message board. I blindly trusted him, and one morning I wake up and I'm locked out of the message boards and he's the leader of the whole thing."

What Wynn discovered to his detriment, however, Fred Thomas discovered to his advantage. Though suited to no activity other than the virtual kind, he began to rise in the esteem of the MOG's ranks by virtue of his energy and the unstinting posts he wrote with military care. Did anyone know he was just a little old man? No, and he found himself in enthusiastic parlay with some of the more radical voices of the MOG, such as "getawayman," who liked to follow quotes from liberal politicians with quips like "far as I'm concerned just another round in the mag babe" and "just waiting to empty a few mags!!!!!!!!!!" Now Thomas's retirement actually served as a benefit, as he had enough time on his hands to volunteer for an "officer" position that no one else wanted. Jimmy Wynn had to struggle to restore his leadership of the Militia of Georgia after Joe Sims unaccountably disappeared; but within months of joining the MOG, Fred Thomas had become Wynn's second in command — his executive officer, or XO — just by raising his virtual hand.

It didn't last long. Wynn has spent half his life in power struggles with half the militia members of Georgia, and Fred Thomas was no different. He objected to Wynn's moderation on the issue of immigration and his opposition to the Iraq War. Wynn met with him face-to-face and noticed that Fred Thomas in person was not exactly the rational radical of the message board. "He tries to be head honcho of everything. He's pretty aggressive." Thomas resigned from the MOG by early 2010, but instead of fading away he called Dan Roberts in Toccoa. They'd both had fallings out with Jimmy Wynn, and they were united in their disgruntlement. What's more, they had an idea for a new kind of militia, smaller, more purposeful, more covert, more selective, more imbued with vision. Fred Thomas reached out to "getawayman." Dan Roberts reached out to Joe Sims.

First, to get the money thing out of the way: Joe Sims wanted to get paid. He had already sent me an e-mail telling me that he wouldn't give me an interview. He would, however, get on the phone to negotiate, and a few hours after I met Charlotte Thomas, Joe Sims called with his pitch.

He said, "I've had my life threatened, I've had my car keyed, I've had my tires slashed."

He said, "I've had Fox up my behind, I've had CNN up my behind, I've had BBC up my behind. Ev-er-y-body wants to talk to me."

He said, "I'm not sticking my nose in any publication unless I'm getting paid. Just to keep me on the safe side. I'm going to use that money to relocate me and fight the problems that I have. I've spent the last year of my life in this mess. I've been in the militia movement for twenty years. I know ev-er-y-body. I know everybody that's considered a domestic terrorist, I know people that should be considered domestic terrorists but aren't yet because they haven't hit the radar. I mean, I am probably one of the most connected militia people on the planet at this minute. I know everybody's dirty little deeds and I have become persona non grata...."

He wound up talking to me for an hour and fifteen minutes, with no compensation. He was fed up with the feds — "They don't return my calls. They don't return text messages. They don't return e-mails. When I called a certain government agency and told them who I was and that I needed to speak to someone, two hours later my handler was calling me and was mad at me for making the phone call." His handler wasn't going to like him giving an interview, either, but Sims didn't care because to his mind, his handler hadn't been taking care of him. "I'll probably be threatened with something, I might go to jail," he said. "I've been threatened with tampering with evidence, lying to a federal officer, blah blah blah blah blah. I just want to be left in a little hole someplace. I don't want to be Joe Federal Informant."

But his complaint about the government in general and his handler in particular was just that — a complaint. In the end he talked because he's a talker, and he wanted to explain himself. He'd been shamed in Anderson — "The typical, 'Oh, he's a pedophile, blah blah blah blah blah.' " But that, he said, "has kind of died out. None of my ex-stepchildren are still in town, so I don't have to deal with that lie. My ex-wife has apparently moved and gotten remarried, so I don't have to deal with her anymore. Everything I have to deal with now is little people coming to town, wanting to ask me about this and ask me about that."

The shame of the pedophile, then, has given way to the more precarious shame of the snitch. "I'm concerned for my safety every time I walk outside. I'm very well known in this town. I'm concerned when I go to the grocery store. I'm concerned when I stop and get gas." But of course the two brands of opprobrium are intertwined: People think he's a snitch because they think he's a pedophile. They think that he volunteered to rat out his fellow militiamen in order to get out from under the charges that he sexually molested his stepdaughters. He can't address the alleged crimes of Fred Thomas and Dan Roberts without addressing his own. And so he told me:

"I never touched my daughters. That was a case of vindictive prosecution."

"I can prove [the child porn] isn't mine. It was all on the hard drive I had that me and my brother-in-law got free on Craigslist in New Jersey. It was not on the computer I used personally."

"I didn't go to Maryland. I was living in New Jersey. I was working for Domino's Pizza. I was picked up on highway 95 going south. I was heading back to South Carolina to answer the charges."

Indeed, Joe Sims is an unusual government asset in that he is a government asset who has not pleaded guilty to the charges against him. He is fighting them and trying to prove that the stepdaughters who stepped up to accuse him are liars. At the same time he is fighting to make people believe that the only reason he told the feds about the plot to kill public officials is that he knew it was happening and was a concerned citizen. And yet both claims are connected, because he didn't try to contact the FBI until he went to jail and had the necessary motivation. What would have happened if he hadn't alerted the feds?

"If they'd pulled this off, tens of thousands of people would have died. So I did the right thing."

Why did he do it?

"To keep people from dying."

You really think that would have happened?

"It would have."

Are you a hero?

"I'm just a grunt. I'm the wrong guy in the wrong place at the wrong time who did the right thing."

One of the peculiarities of the federal policy of preemption, however, is that the right thing is usually inextricable from the wrong thing. And one of the things that the story of Joe Sims asks us to believe is that our safety was purchased by his sin — that we were spared because two girls in Anderson, South Carolina, say they were not.

On October 29, 2010, Joe Sims posted on a militia site on the Internet. He'd been out of jail for nine days, but he did not say where he'd been or why. He just announced his return:

another old face checking in hello from sc

time for a change

Seven days later, he began posting again on Jimmy Wynn's MOG site, the Liberty Forum. It was another reintroduction. He wrote: anybody here from toccoa? wondering how my old unit is doing?

And then he kept posting. Over the next three months, he was one of the most active members on the message board. He posted about rebuilding the Toccoa unit of the MOG; he posted setting the date for meetings; he posted to recruit "three lieutenants" for Toccoa; he posted to list his phone number

and Web address; and he posted to name himself "captain" of the Toccoa unit. He posted with manic fervor, and finally Wynn stepped in. They got into a flame war over Sims's right to call himself "captain," and on February 19, Wynn informed members that "on February 15, Joe Sims was removed as Captain in the Militia of Georgia." A month later, he went further, calling Sims "a danger to the movement," and issuing a warning: "If you associate with this gentleman and end up in jail, I am going to come and visit you and tell you I TOLD YOU SO."

It was too late. Sims had already attended the meeting at the house of Fred and Charlotte Thomas. And this is how he responded to Wynn a day later:

hahahahahahahahahahahahahahah now this is your best stunt ever jimmy winn your responding to a post that you deleted hahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahah your talking to your self out loud over the internet and under multiple screen names again you really need to get some meds.... ☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺

☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺☺

joe sims poseur come to some meetings your welcome we need entertainment

I asked Sims about these posts. He had told me that he had no leadership role in the "covert group" started by Thomas and Roberts — "The only thing I was, was another soldier." But here the soldier contradicts himself by calling himself the captain.

"That was trying to build up the militia," he explained. "That was what they wanted to do."

He posted like that because he was following orders issued by Fred Thomas and Dan Roberts?

"That's what they wanted to do."

This cannot be true. Sims wasn't working for the "covert group" when he was posting on the MOG message board. He was working for the FBI. He had been working for the FBI since December and trying to work for the FBI since he got out of jail, and so in his posts on the MOG message boards he was either putting on a show or casting a net. What he was not doing was following the orders of the conspirators. There were no conspirators at that time. There was no conspiracy. The covert group was not the covert group until the first meeting, and Sims had not yet met Fred Thomas. Indeed, in February, when Sims was at the frenzied peak of his posting, Fred Thomas was in the hospital getting his lung excised. The government has asked us to believe that Thomas and the others were inherently dangerous — that their conspiracy had started without Joe Sims and would have kept going without Joe Sims. But Sims was inherently catalytic, both online and off. He was working hard even before the conspiracy was afoot, and he kept working hard for its duration. He had to. The conspirators were frail old men, stranded at the corner. It took a much younger man to help them all across the street.

Of all the men, Dan Roberts was the closest to being what he said he was. He had bled for his country. He had spent all his life in the mountain town of Toccoa, Georgia, and he had suffered disfiguring wounds in Vietnam. He was thickset and potbellied, with a thick head of silver hair; he was quiet and kindhearted, with a passion for rescuing dogs with his wife, Margaret, and buying bags of dog food for those who couldn't afford it.

He was also a longtime militiaman who had captained the "Toccoa unit" both before and after the arrival of Joe Sims, and an ardent defender of the Confederate flag; he had helped lead protests when the local middle school banned the flag's display. The protests had gotten out of hand, and a friend had gone to jail. By the time Fred Thomas called him, "he had pretty much gotten out of" the militias, says Margaret Roberts. But anyone who lived in Toccoa still knew where Dan Roberts stood, because if the front yard of his house was notable for its population of rescued mutts, the property he owned next door was notable for the bucket trucks he used for his sign business and the three flagpoles flying the American flag, the old Georgia flag that incorporated the Confederate one, and the battle flag of the Confederate army.

Roberts had associated with some racist groups when he was orchestrating the flag protests. He was not, however, known as a racist, and sometimes he went camping with a black friend named Anthony Howard. Howard was sympathetic to the militia cause; hell, he was sympathetic to the Confederate flag. He was in his early forties, and he had been court-martialed from the armed services. He was a long-distance trucker who lived near Savannah and who was known for driving great lengths to do the militia's recruiting work. He was also known both for being hotheaded — he had both joined and left most of the militias in Georgia — and increasingly "radicalized," in the words of a female militia member named Jaimie Blackstone. He was "getawayman" of the MOG message boards, and his posts, particularly those in answer to "Ahab," seem plainly unhinged. Indeed, when Joe Sims went back to the FBI's joint task force after failing the polygraph in jail, it was the name of Anthony Howard that restored his credibility. Sims told the FBI that Howard was using his truck to run guns, and Howard became someone the FBI was "interested in."

They were not interested in Fred Thomas. Like Sims, they barely knew who he was. But Dan Roberts invited Sims to a meeting at Thomas's house, and when Sims heard that Anthony Howard was also going to attend, Sims told Agent Matthewson. On March 17, Joe Sims went for the first time to the home of Fred and Charlotte Thomas. He brought his son, because he didn't have a car. His son gave him a ride. But Scott Matthewson equipped him with a tape recorder, and then waited near the Thomases' house. When the meeting was over, Sims gave Matthewson the tape recorder back. Matthewson took the machine, and pressed play.

The FBI would never lack interest in Fred Thomas again, for he was not Fred Thomas at the meeting. He was Ahab. He spoke of the program of "patriotic assassinations" he introduced in an early post on the MOG message board, but now without disclaimers. And so the template for the conspiracy was set from the start: Joe Sims wearing a wire and Fred Thomas being extravagantly self-incriminating. But conspiracies need bodies, and this one lacked them. Sims never brought his son back; Anthony Howard's first meeting was his last. Two weeks later, on March 30, he was arrested crossing the Canadian border in his truck. It was not for gun running; it was for possession of two handguns, a .22 and a .380, and for possession of child porn on a computer. His arrest may have been the result of a random stop; when asked if he had anything to do with it, Sims answered, "Not that I am aware of." But this stretches credulity. Howard has pleaded guilty. He is in jail awaiting sentencing and is considered likely to testify against Fred Thomas and Dan Roberts as authors of a conspiracy that after its first meeting lacked members, lacked money, and existed nowhere but in the suspicions of the FBI and the heads of two old men.

There were a lot of meetings — more than twenty of them referenced in the federal indictment alone. There were meetings at the Waffle House and the Shoney's. There were meetings at the homes of Fred Thomas and later of Ray Adams. There were a few car rides. Once Sims drove with Thomas to downtown Atlanta, and they cased out federal buildings. He also drove Thomas and Roberts to a militia gathering near Valdosta, Georgia, and to a roadside rest stop where Sims introduced them to a man who would turn out to be a second confidential informant and who said he could get them guns and explosives. There was the addition of Ray Adams and later still Sammy Crump, the first with experience working for the Department of Agriculture, the second with experience doing maintenance work for the Centers for Disease Control. These guys were brought in to make ricin, and two weeks before he was arrested, Crump was so enthusiastic about the prospect that he's quoted as saying that if the ricin works, they can get the financial backing to go to Africa and get the ingredients for botulism — "I know somebody can make it."

Listen: Sammy Crump was never going to go to Africa. He was never going to make botulism, and he wasn't going to make ricin, either, despite shopping for things like lye and acetone and having a stash of castor beans. The preposterous extravagance of his plans should have been exculpatory. As you listen to him on the tapes, you just want someone — perhaps Sims; maybe Scott Matthewson, the FBI agent who collected many of the tapes from Sims once they were made — to tell him to just stop, the show's over, time to go home. Instead he's fixed to a conspiracy to make weapons of mass destruction. The first thing you ought to know about the conspiracy is that it could have been stopped at any time. The second thing is that it never was.

It never stopped. It didn't stop, even after Thomas found out that Joe Sims had just gotten out of jail and that Anthony Howard had been arrested, because Dan Roberts vouched for Joe Sims. It didn't stop, even when Fred Thomas told the undercover agent that they didn't have the money to buy what they wanted; it didn't stop even when Dan Roberts is heard on tape worrying that they're stepping into a sting. It didn't stop because it was powered by Fred Thomas's Ahab-like obsessions and Joe Sims's need to stay out of jail. It didn't stop because the old men had too much time on their hands and the government had too much invested in the outcome.

Sims says that he was scared of the old men, because they came armed to every meeting, when all Sims had was a Gerber knife. He says, "If I wasn't the kind of person I am, I'd be shaking constantly. And a couple of meetings I was shaking constantly." But if this is the truth, he was good at hiding it. He was the one constant in the conspiracy. He figured in nearly every interaction and in all his interactions displayed a cool understanding of what the men wanted to hear, especially Fred Thomas, the old man Sims called "Mr. Fred" and "young man."

"My dad actually thought this guy was gay," says Sam Crump's daughter, Karon Bond. "He literally followed him everywhere. If my father wasn't at the meetings, he'd text him: Where you at? He'd call him: Where you at? It's pretty scary, that this person can insinuate himself and then get you to say the one thing that puts you in prison for the rest of your life."

On the Saturday before Dan Roberts was arrested, Margaret Roberts went to his office. It was in the lot next to her house, the lot where Dan parked his bucket trucks and flew the rebel flag. She opened the door, and there was Joe Sims, sitting there with Dan and Sammy Crump. She had met Sims a few years before and had detested him on sight; whenever she picked up the phone and he was on the other end asking for Dan, she tried to let him know she had no use for him. "You remember Joe Sims, don't you, Margaret?" Dan said.

Sims looked at her. "Aw, I don't think she remembers me, Dan," he said.

"I remember you," Margaret said, then turned around and left. Later, she told Dan that he was "just trouble," but by this time Dan Roberts had bigger worries. "They'd actually decided to back out," she says. "Dan had gone to Fred and said, 'You better stop this, Fred, it's gone too far.' But Fred was scared. Joe Sims had a roll of money, and Fred was scared about what was going to happen if the deal was called off. That's why Dan went. He feared for Fred's life, and didn't want Fred to go alone. But they didn't bring any weapons, and they never did touch that money."

This is not exactly true. The money was the money necessary for Dan Roberts and Fred Thomas to buy a silencer and a cell-phone-activated improvised explosive device from the undercover agent posing as an arms dealer. Dan Roberts didn't have it, so he might not have touched it. But according to sworn FBI testimony at a subsequent bond hearing, Fred Thomas had it, and bartered a pistol to help defray the cost. And Joe Sims had it, despite being jobless since getting out of jail. He got the money — the roll of bills — from the same place the undercover agent got the silencer and the replica of a claymore explosive: from us. It is our money financing a policy that treats the inclination to commit acts of terror the same as the acts themselves. It is our money furthering terrorist plots that — in the case of the geriatric jihadists, anyway — could have been stopped with a Post-it note on Fred Thomas's front door.

And so on the morning of Tuesday, November 1, Fred Thomas and Dan Roberts met with Joe Sims and his roll of cash in the faraway end of the vast parking lot of the new Walmart in Cornelia, Georgia. He was with the undercover agent in a white Ford truck with Virginia plates, and just before lunch, they all got in. Dan Roberts was in the backseat with Joe Sims; Fred Thomas was in front, doing the talking.

He had written in his introduction to the Militia of Georgia about the blood that he'd shed for his country. He'd told the undercover agent "I've been to war, and I've taken life before, and I can do it again." He had never done any of it. He was in the Navy; he had never shed blood, nor had his blood been shed. He was in the grip of fantasy, from first to last, until the money was handed to the driver of the white truck. Then a van and a Chevy Suburban came wheeling through the lot, and as they ripped past some workers from the Captain D's on their way out to lunch, one of them said, "Don't look now, but there's a SWAT team in that Suburban."

Then all four doors of the Suburban opened simultaneously, along with all the doors of the minivan. The SWAT teams jumped out and threw their flash grenades, and in the thunderclap that followed they pulled Thomas and Roberts out of the car and pinned them facedown on the ground with their hands trussed behind their backs and a circle of automatic weapons trained on their heads. At the same time, Sammy Crump was being arrested at a gas station in Toccoa; Ray Adams was being arrested near his house in his car; Margaret Roberts was being mistakenly handcuffed after coming home to meet Dan for lunch; and the door to Charlotte Thomas's Sinatra shrine was being kicked in while flash grenades exploded on the floor. A parade of law-enforcement vehicles from jurisdiction after local jurisdiction rolled into the lot, and after spending about twenty minutes with their faces pressed against asphalt, Fred Thomas and Dan Roberts were allowed to stand up. They both looked a little sheepish. Both of them had pissed their pants. And when they looked around for Joe Sims —

"That son of a bitch," Dan Roberts said.